If you’re going on a trip to Copenhagen next year, forget about sending a postcard. From the end of 2025, Denmark’s national postal service, PostNord, has announced the removal of all 1,500 postboxes across the country and a total cessation of letter deliveries. Edged out of the market by parcel delivery services and digital communications, postal services can no longer see a business case for these frivolous rectangles of card.

We’re all digital these days, and so the once-beloved holiday postcard is dead, it seems to say. But is it?

I’ve spent the last couple of weeks looking into the history and fate of the postcard. Is it a relic of holidays past, or does it have a place – besides being relegated to a collectible souvenir – in today’s digitised world?

It turns out that the humble postcard, since the very start, has been the master of reinvention. From its beginnings as a communications innovator to its popularity in niche communities today, it’s moved with the times and flexed to suit our needs for over 200 years. Whatever PostNord and Royal Mail say, it isn’t about to stop now.

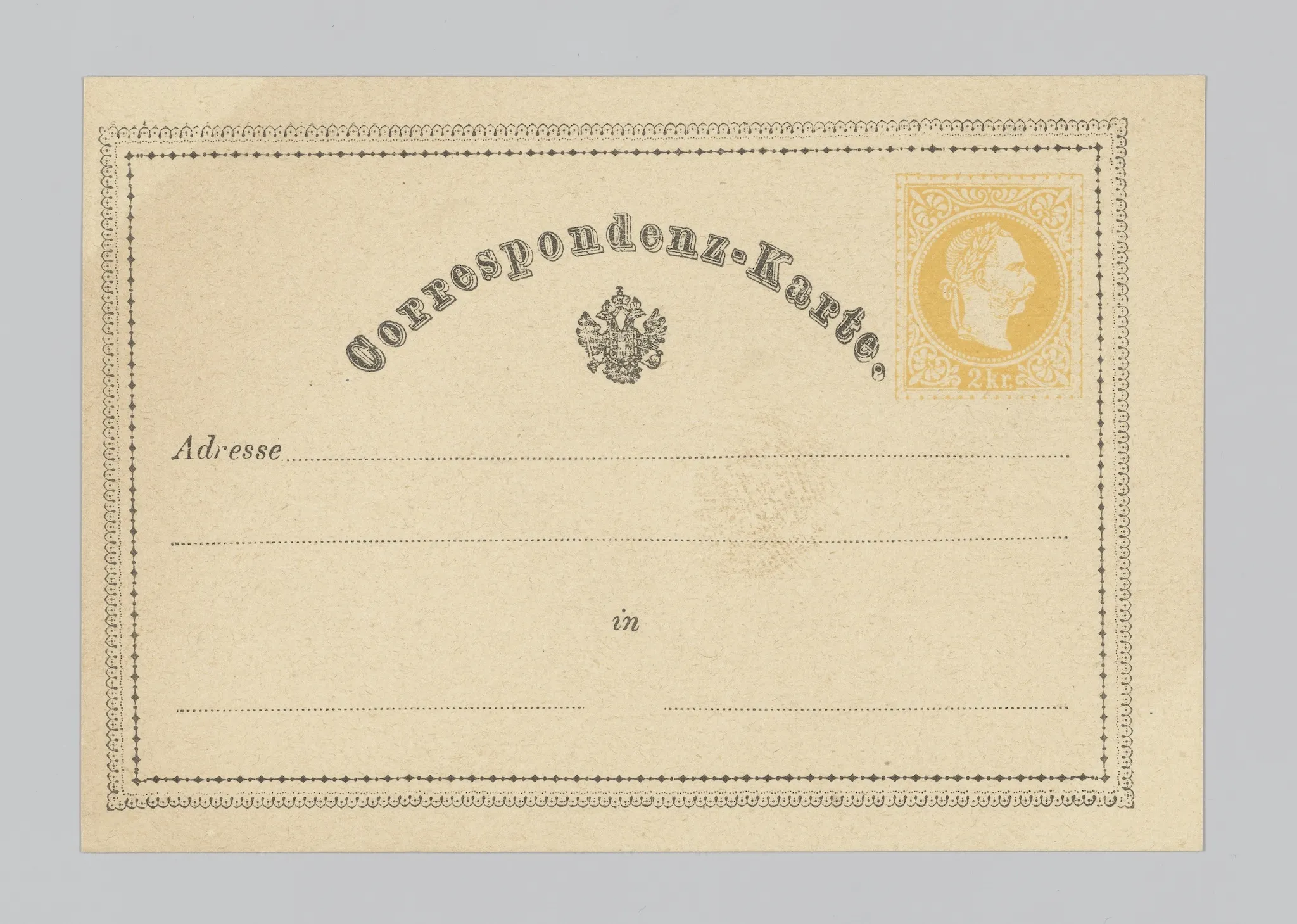

When postcards arrived in Britain in 1870, they were seen as the fastest and cheapest way to send a message, Georgina Tomlinson, curator at The Postal Museum in London, told me.

‘It cost half the price of a letter when it came in, and was seen as a postal innovation,’ she said. ‘They looked quite different then – one side was for the address and the other for the message – but everything was public just like it is today, so the maid and the postman could read what was written, which the Victorians found rather difficult.’

It has something in common with the advent of WhatsApp – suddenly, everyone could communicate significantly quicker with each other, and it really took off. Pictures started appearing on postcards in the late 1800s, and led to a boom in postcard collecting. The way people communicated changed too: the Victorians developed systems and codes to do with how they stuck their stamps on, sending secret messages in Morse code and using mirror writing to make sure the postman couldn’t read what was written.

Loose lips sink ships

‘The golden age of the postcard was considered to be 1902-1918, until the end of the First World War,’ said Tomlinson. ‘At their peak, 900 million postcards were delivered [per] year within the UK.’

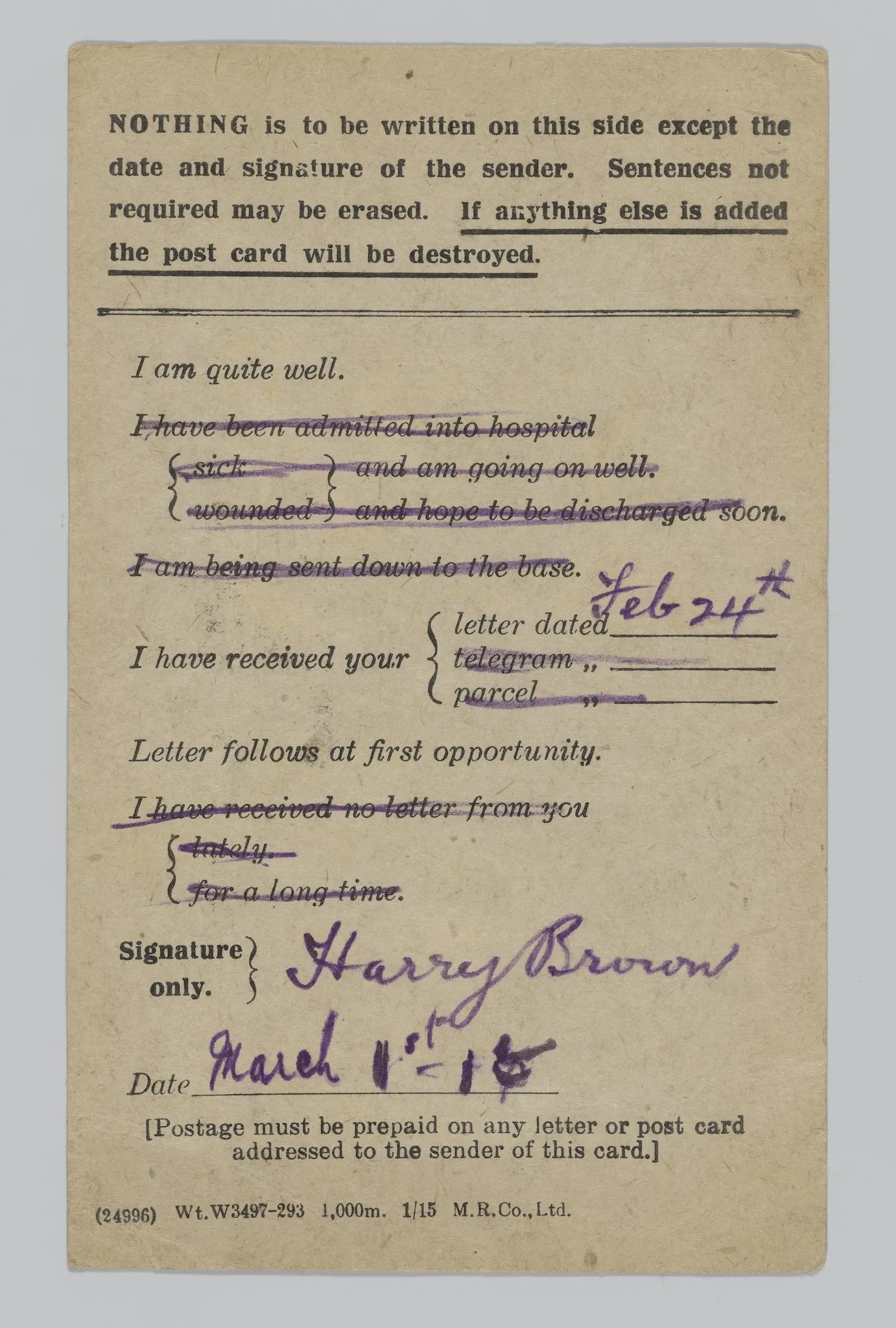

It was at this time that the postcard changed again. They were not only a quick, cheap way to send a message; they became an important morale booster, an essential message giver, and a lifeline to those back home. Soldiers were given free postage and encouraged to write home, even if just to say ‘O.K.’

The Field Service postcard was developed with prewritten text that said things like ‘I have been admitted into hospital’, ‘I received your letter dated…’, and ‘I am quite well.’ Censorship was important – frontline soldiers couldn’t say too much – and it was important for morale back home that not too much was shared, but that something was said all the same.

Wish you were here: The holiday postcard is born

The traditional holiday postcard as we know it today came into play in the post-war period, when leisure and happiness were on the nation’s mind again, and seaside resorts across the UK started to boom in popularity.

The 1930s saw the advent of a particularly lewd brand of seaside postcard, featuring illustrations of buxom young women and innuendo-charged slogans. They became subject to censorship by the 1950s Conservative government, and by the ’70s these ‘tacky’ postcards were in decline – today, they’re collectors’ items.

It was during the twentieth century that international tourism took off, and with it, the holiday postcard industry entered its heyday. Landmarks like the Eiffel Tower were featured on some of the first holiday postcards, and as more and more people took trips for leisure, it became common to send a memento to loved ones when travelling abroad. Pre-text messages – and long before social media – we’d show off about our travels to a select few people via a humble piece of card.

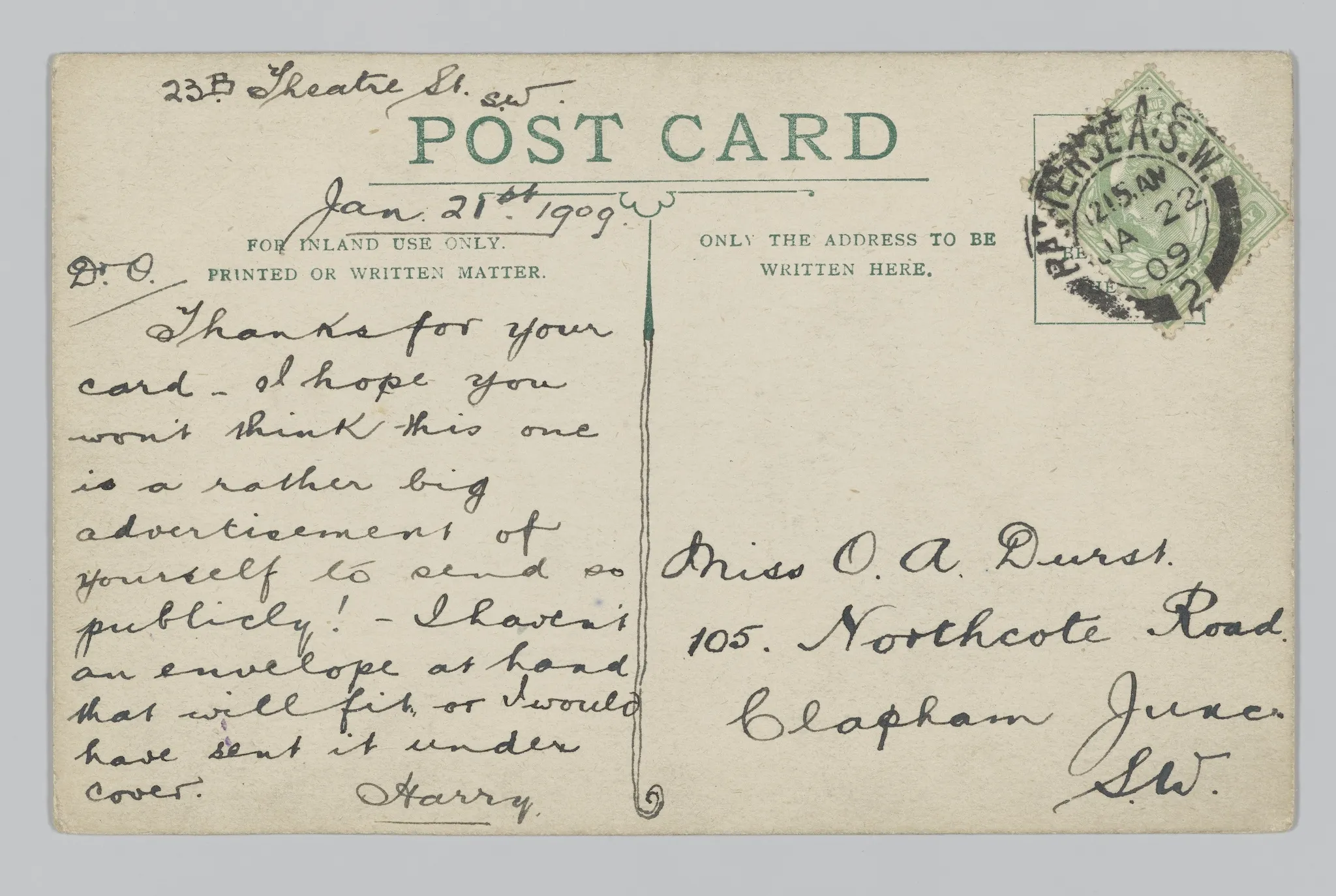

That’s the thing about a postcard – it offers a snapshot of history

‘That’s the thing about a postcard,’ said Tomlinson, ‘It offers a snapshot of history.’ And it offers more than that, too: among The Postal Museum’s collection is a series of postcards from Harry to his girlfriend Olive, from the 1900s. The couple lived 15 minutes walk from each other, and he sent beautifully designed postcards to her. The stories postcards can tell about us, as well as to us, illuminate how we lived, loved and behaved. It’s all rather romantic.

A new era of slow communication

Fast forward to today, and the slow decline of physical mail, along with ease of quick communication and social media, has in turn led to the decline of the traditional holiday postcard. You might buy one on holiday, but in lieu of stamping it and sending it a loved one, it’s more likely you’re picking one up as a souvenir, like fridge magnets or shot glasses.

Personally, I can’t remember the last time I sent a postcard. A couple of years ago, a friend of mine sent me a postcard with an illustration of a dog on it because she thought I’d like it, and I’ve got an unhealthy collection of art and museum postcards, but it’s unlikely they’ll ever see the inside of a postbox.

That’s not to say that the postcard is a thing of the past: far from it. It’s weathered Victorian prurience, two world wars and cartoonish sexism, and is finding its way through digitisation too. Forget fast and cheap: the postcard today is becoming a channel for thoughtful, slow communication.

‘We have just launched postcards,’ said Rosanna Irwin, founder of Samsú, a series of off-grid cabins in Ireland that focus on reconnecting with nature and disconnecting from the digital world. ‘Guests get a postcard each and are encouraged to write a little note to someone that they thought of when not on their phones.’

Forget fast and cheap – the postcard today is a channel for thoughtful, slow communication

It’s a perfect fit for their digital detox cabins, where the focus is on slowing down and escaping to nature. Irwin is not the only person who sees a future in the medium: through a callout on social media, I was deluged with responses by people who send postcards religiously to their grandparents and old friends, and others who collect postcards for art projects, send them to old people in care homes and cherish them as a means of communication that is loved by sender and receiver alike.

For graphic designer Caitlin Welch, it’s the slowness that makes them special: ‘They fall into the same category as film photography and the sound of the ice cream van,’ she said. ‘Slow, but worth the wait. In a world where everything feels almost instant and never-ending, it’s such a pleasure to wait.’

A need for human connection

I found people all over the world using postcards in novel ways, from a restaurant in Maine where dinner reservations are only available to those who apply by postcard, to German artist Gudrun Gempp who sends beautiful handmade postcards to anyone who asks, and slow-living nature-loving Somerset bookshop Sherlock & Pages, where the owner curates a wall of postcards sent in by loyal customers. There’s even a competitive postcard exchange project called Postcrossing that encourages people to send random postcards to strangers all over the world.

What it’s told me is that the postcard is not dead: it’s been reborn for the digital age. While it’s easier now to send a snap of your holiday and a ‘wish you were here’ via a quick text, sometimes digital communications lose connection and a deeper meaning along the way. The way postcards are being used now is about holding on to that human connection. It’s a note that’s just a bit more special because it doesn’t come in an effortlessly easy digital form, and something that puts a smile on your face when it comes through the mailbox. It’s not dead, not quite yet. Long live the postcard.

Stay in the loop: sign up to our free Time Out Travel newsletter for all the latest travel news and best stuff happening across the world.