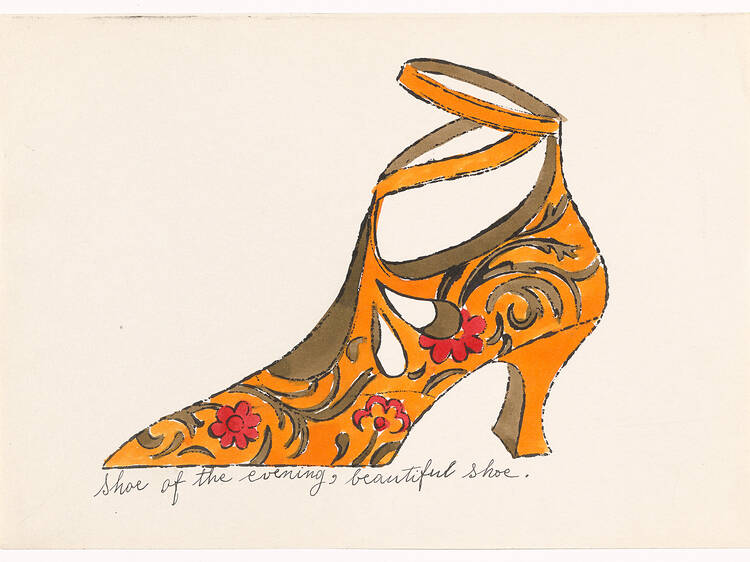

Andy Warhol (1928–1987) was born Andrew Warhola, Jr. in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. He originally planned to become a teacher, but wound up at Carnegie Mellon instead, where he studied design. In 1949, he moved to New York, establishing himself as a commercial designer known particularly for his shoe illustrations for I. Miller.