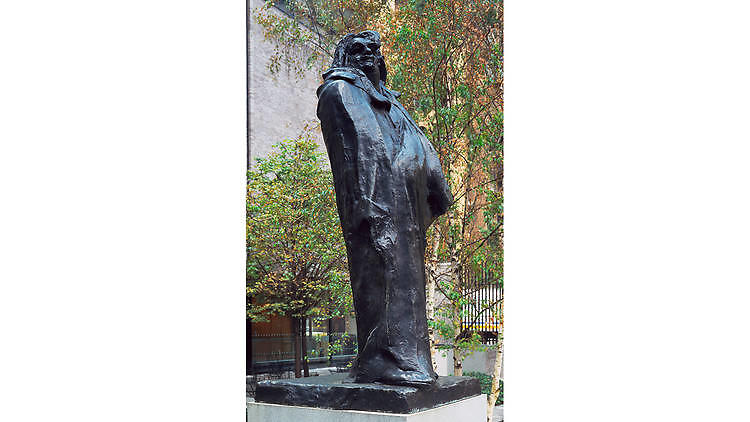

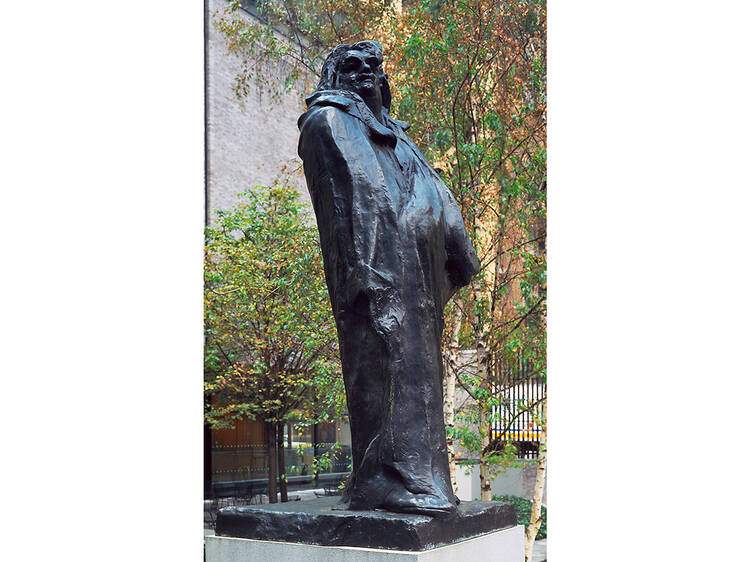

Auguste Rodin, Monument to Balzac (1898)

Rodin (1840–1917) won the commission for this homage to novelist Honoré de Balzac after the artist originally selected for the project—the neoclassicist Henri Chapu (1833–1891)—died before work could progress. Sponsored by France’s Société des Gens de Lettres in 1891, the sculpture was supposed to take 18 months to complete. However, Rodin, taking a kind of method-acting approach, immersed himself in the life and work of his subject. Instead of 18 months, it took Rodin seven years and 50 different studies (as well as side trips to the Balzac’s hometown, and asking Balzac’s tailor to replicate the author’s clothes) to deliver a full-size plaster maquette. Almost immediately, it was roundly castigated by critics and rejected by the Société for being too radical. It’s easy to see why: Balzac is depicted as an abstracted column with only his head visible above a cloak representing the one he wrapped himself in while writing. Defending himself against the naysayers, Rodin insisted his aim was to capture Balzac’s persona, not his likeness, which may account for the fact that the first bronze of the piece wasn’t struck until 1939—22 years after the artist’s death.