There’s a moment that stays with you at Angélica Cocina Maestra, the restaurant at Catena Zapata winery: sweetbreads with beet purée, beurre blanc, and house-made vinegars, served alongside the “mothers” of those vinegars. This isn’t just another condiment—it’s the result of careful fermentations that bring acidity and fragrance.

Adding to the experience is a remarkable anecdote: a “barter” between chefs Juan Manuel Feijoo and Josefina Diana and a Chinese diner, daughter of a vinegar-producing family. Fascinated, she exchanged an aged millet vinegar she carried in her handbag for two local creations. “It’s incredibly valuable and we treat it like gold,” they recall.

That gesture confirms what’s happening in Mendoza: artisanal vinegar is back, now reimagined by chefs and producers. Cooks are experimenting with their own batches, and Alquería has emerged as Argentina’s first winery dedicated exclusively to varietal vinegars, already awarded at international competitions. This movement aligns with a global trend—reclaiming fermentation and elevating products once considered secondary. Vinegar proves versatile, aromatic, and terroir-driven, winning over kitchens and adventurous palates.

How is vinegar made?

For decades, vinegar played a minor role—reserved for salads or pickling. Today, it’s experiencing a renaissance in contemporary kitchens. It’s treated as a noble ingredient, capable of expressing both terroir and the cook’s hand. “Vinegar is a luxury, not because it’s inaccessible, but because it’s singular: it transforms from something alive, which makes it unique,” says the team at Angélica Cocina Maestra.

“Vinegar starts out as an alcoholic beverage that then oxidizes to produce acetic acid. If we had to define it: it’s an oxidized alcoholic drink that goes through a process to become sour,” explains Martín Russo of Ánimal, the restaurant at Bodega L’Orange in Chacras de Coria.

There are three main methods, each shaping the final character of the vinegar:

-

Oxidizing alcoholic beverages such as wine, beer, or cider.

-

Creating an alcoholic fermentation from fruits (figs, apricots, plums) and natural sugars like honey or molasses, which yeasts consume before transforming into vinegar. “You’ve got an almost infinite range of base products to work with—it’s 100% natural,” Russo notes.

-

Infusing herbs, flowers, or fruits into grain alcohol, then oxidizing it.

The key lies in the producer’s choices: which fruits, herbs, or resting times to use. But experimentation doesn’t always succeed. “There’s a lot of trial and error in this world. We’ve discarded many batches, and we’ve had some exquisite ones we could never replicate,” admits Diana.

Vinegar’s rise fits into today’s global table: ferments, layered acidity, and freshness. No longer just sweet or savory, flavors now include sharp, bright notes that expand the sensory palette. “We’re drawn to vinegar because of its freshness and the creative world of flavors and aromas it opens up,” say local vinegar makers.

"Vinegar opens up a creative world of flavors and aromas"

Alquería: Argentina’s first varietal wine vinegar winery

Until recently, talking about vinegar at the table seemed unusual. Today, Mendoza boasts Alquería, the first production facility in Argentina devoted exclusively to varietal wine vinegars. Founded by the Inchaurraga family, it has spent more than 30 years perfecting the art of crafting authentic, high-quality vinegars.

“Vinegar has always been sidelined in the kitchen, but it has enormous potential if made with the same respect as wine,” says Natalia Inchaurraga.

Their method begins with carefully selected wines, followed by submerged-culture fermentation using chosen bacteria. The process may last a week, then rest in tanks or barrels for six to twelve months, developing the complex notes that make each vinegar unique.

Each variety preserves the character of its base wine. Cabernet Sauvignon brings a spicy, fresh profile, with oak-aged versions offering structure, toasty notes, and a creamy bitter finish. Tarragon-macerated Cabernet results in an elegant, fresh vinegar with spicy, light, sweet notes, honey-like aromas, and herbal touches. Torrontés wine vinegar offers caramel and honey notes alongside floral and herbal hints.

Alquería’s work has been recognized internationally, winning gold medals at Spain’s Vinavin competition, including the Gran Oro (top prize) in 2024 for their tarragon-macerated Cabernet Sauvignon vinegar.

"It’s an ingredient of astonishing versatility"

Vinegars at Ánimal: 100% natural fermentation and creativity

At L’Orange, Joanna Foster and Ernesto Catena´s winery, small-batch artisanal vinegars are made from seasonal fruits. Chef Martín Russo leads the experiments: one summer, they used plums to produce a violet-toned vinegar; another batch involved cloudy, rustic organic apple vinegar, ideal as a “mother” for other fermentations.

“Vinegars are like SCOBYs—colonies of bacteria and yeast that can inoculate new batches. And like wine, they can age: they improve over time and let you build a ‘vinegar cellar,’” explains Russo.

At Ánimal, vinegar is part of the restaurant’s identity. Their modern Mendoza cuisine pairs fresh vegetables with vinaigrettes made from olive oil, preserved lemons, and house vinegars. “Artisanal vinegar is exquisite, complex, and easy to enjoy—you won’t find it anywhere except where it was made.”

They even use vinegar for its aromatic qualities. “With a fig-leaf vinegar, we brushed the plates, and when plating burrata, it felt like eating under a fig tree.”

Still, balance matters when pairing vinegar-rich dishes with wine. “When wine is the star, vinegar’s acetic or volatile notes shouldn’t overwhelm the experience. The best way to pair is to produce low-acidity vinegars that can be used without clashing with the wine,” says Russo.

Angélica Cocina Maestra: vinegars designed for wine pairing

At Catena Zapata’s restaurant, the guiding principle is Wine First: wine leads the menu. Each vinegar is crafted with pairing in mind, in constant dialogue between kitchen, winemakers, and sommeliers. Acidity, texture, and aromatic profiles are all chosen in relation to the wine.

“For the Huerta dish, which paired with Merlot, we highlighted fruit with bitter leaves and a lemon verbena vinaigrette with just the right acidity,” say chefs Juan Manuel and Josefina, along with vinegar specialist Tania Torres.

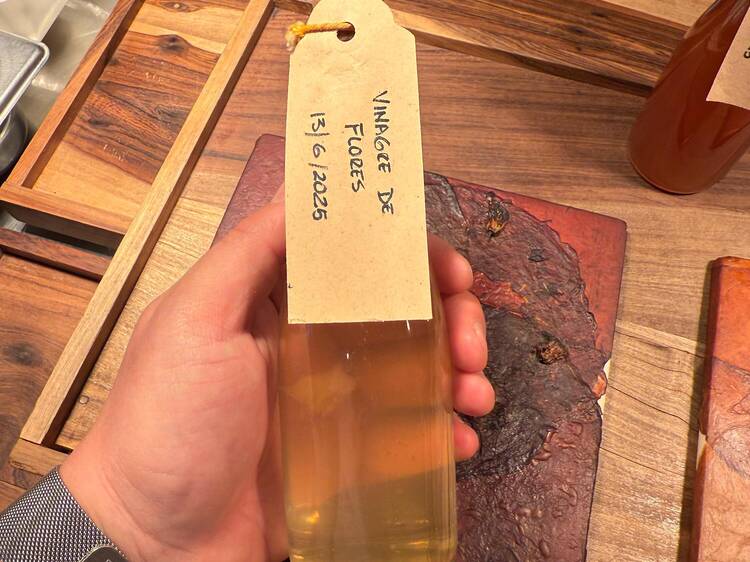

They capture seasonal aromas—figs, flowers, verbena, ginger, lemon, beetroot—turning them into vinegars that appear in dressings, sauces, and vinaigrettes. “We always want to go further: each vinegar has a distinct profile, and we love working with that acidity,” says Josefina.

Guests are often shown the dehydrated “mothers” to appreciate the process. Highlight dishes include sweetbreads or beef with baby greens and herb-infused vinaigrette, showcasing how central vinegar has become.

Ruda Cocina: a world of floral macerations

At Tupungato Winelands, chef Gastón Trama leads Ruda, a restaurant exploring cold macerations in grain alcohol vinegars. With abundant flowers and botanicals from their garden, they create unique aromas.

“Once we used an over-fermented kombucha and got a purple carrot vinegar with a gorgeous violet hue. We used it in a vegan tartare with sugar-cured SCOBYs, served alongside soy-glazed watermelon,” recalls Trama.

This exploration began as a necessity: their cuisine leaned sweet, so with sommelier Camila Cerezo, they decided to add acidity through ferments, pickles, and vinegars.

Examples include a gel topping their fosforitos (puff pastry snacks): a mix of sriracha, quince in syrup, and floral vinegar to balance flavors. Or chamomile macerated in-house, blended with cashew purée for an impressive finish.

With diverse projects and unique experiments, Mendoza is rewriting vinegar’s story. Once a secondary condiment, it has become an artisanal ingredient with terroir identity and infinite possibilities. An acidic revolution that’s only just beginning.