Milo Lockett arrived in Buenos Aires with Irupé, his new show at PATIOarts (free to visit until August 22 at Patio Bullrich), and takes the opportunity to speak candidly about what drives him most: art as an accessible language, his love for drawing, the connection with the audience, the demands of the art circuit, and the importance of returning to simplicity. Like his paintings, Milo speaks directly, without detours, with that mix of tenderness, mischief, and lucidity that has made him one of the country’s most popular artists.

“Irupé” is the name of a flower from the Litoral region, but it’s also the title of your current show at Patio Bullrich. What drew you to this figure, and what were you trying to convey through it?

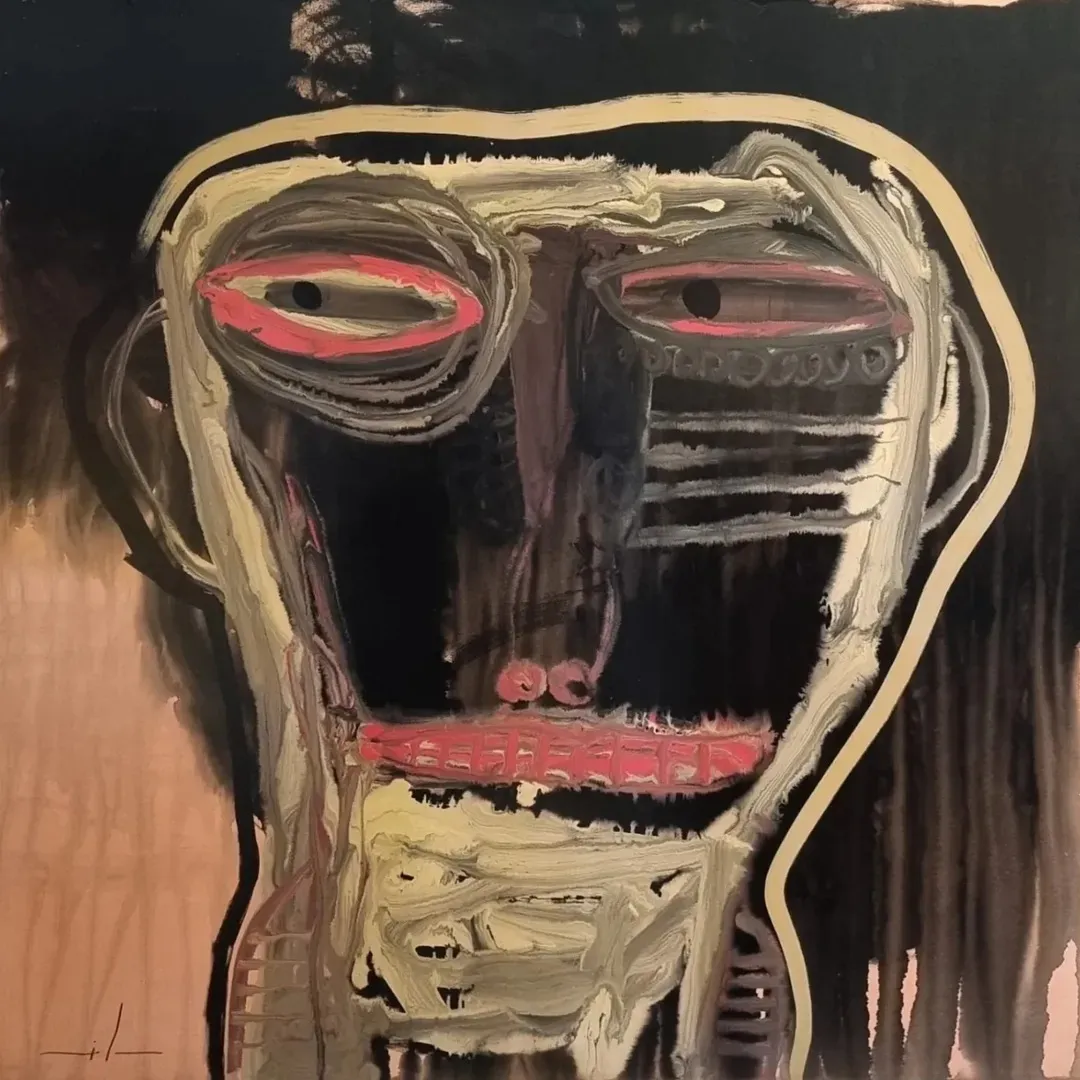

Irupé is a Guaraní legend about love, beauty, and connection with nature. I felt very connected to the neighborhood where Patio Bullrich is located because I lived there for many years. When I was offered the exhibition, I had just started working with clay, mixing it with paint to create different colorations. My work is very colorful, but at the time I was exploring a sort of negative of color: working in burgundy and raw tones, dirty browns with a sand hue, turquoise/light blue on a butter-white background. I was looking for another type of coloration through clay.

Between 2009 and 2010, I worked a lot with the decomposition of the neighborhood, and like many things we leave aside, they eventually resurface. Irupé reminded me of all that — a return to my roots, being close to my neighborhood, in a place where I spent many years. I have dear neighbors there, so all of this is why the show is named Irupé.

"Irupé reminded me of all that — a return to my roots, being close to my neighborhood"

The show is free to the public. What makes it special for you to present your work in such an accessible and open space?

I think there’s a global shift happening where art is no longer a niche. There’s still some resistance in the art establishment, which believes art should be for a few people — and that’s very snobbish. They want to keep it elitist, which feels very outdated to me. I believe art is a universal right. We all have the right to look at art, to make art or at least attempt it, and to play with art. It transcends the old mandates that still exist in the closed circles of contemporary art.

"There’s resistance in the art establishment, which thinks art should be for a few people — and that’s very snobbish"

Your drawings have a sense of childhood — simple and direct emotion. Do you feel that your work helps people connect with what they feel?

Art can often be judgmental, even artists judging other artists. I think everyone has the right to draw and paint, and we all have an innate idea of what drawing and artistic expression are. Our first human expression is drawing — even before words — and we often don’t value those early scribbles, which can define our personality, emotional security, and emotional intelligence.

It’s terrible that we still question whether a drawing is by a child or an adult, whether it’s “good” or “bad.” That’s tied to a social mandate within the art establishment, which often doesn’t focus on bringing art to where it should go or doing with art what it’s meant to do: play, have fun, and enjoy it. Being able to look at art is wonderful because it makes us a bit more sensitive.

You’ve created murals in hospitals, worked with children, and supported charity campaigns. Why do you feel art should be present in these spaces?

I think it’s good for each person to choose their role or prominence in art. I like interacting with people, and I constantly do things to achieve that. I love being invited to paint a mural on the street, in a school, or in a hospital. These are common places where everyone passes through, where everyone has experiences, and it’s great to do simple, normal things in art — things that don’t aspire to be “masterpieces.”

We need to think about new ways to approach art, especially for children. When artists donate our time and presence, we show that we are normal human beings, ordinary people working in this field. You don’t have to be special to be an artist — quite the opposite. We are just one link in the human chain.

"Artists are just one link in the human chain"

You said Irupé is a prelude to what’s coming, and that you’re returning to clay and water. Can you give us a spoiler about what’s next for Milo Lockett and his art?

I’m returning to working with clay and experimenting with some elements mixed with synthetic materials. I enjoy color exploration. I’m taking a bit of a break from color but always seeking alternatives. I’m also working on wood, fabric, canvas, and paper. What I’m showing at Patio Bullrich is what I’ve painted most recently this year. I was surprised because usually people take a year or more to assimilate a change, but this time it was much faster. I’m happy — it’s been a busy year in the studio with a lot of painting, and I feel very satisfied.

Quick-fire Buenos Aires & art Q&A

A Buenos Aires museum where you could get lost without watching the clock: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, without a doubt. One of the most important museums in Latin America, with over 11,000 works.

A Buenos Aires street corner that could be one of your paintings: The corner near La Biela.

Where in Buenos Aires do you feel the city becomes more playful? Around the Museo de Bellas Artes, with the tree-lined streets and even near the public TV station — a beautiful place to walk, a place to play.

A local artist who moves you today: I like many, but Guillermo Kuitca always impacts me.

Your favorite Buenos Aires neighborhood: Recoleta.

A café to sit and contemplate the city: Prado y Neptuno, Ayacucho 2134.