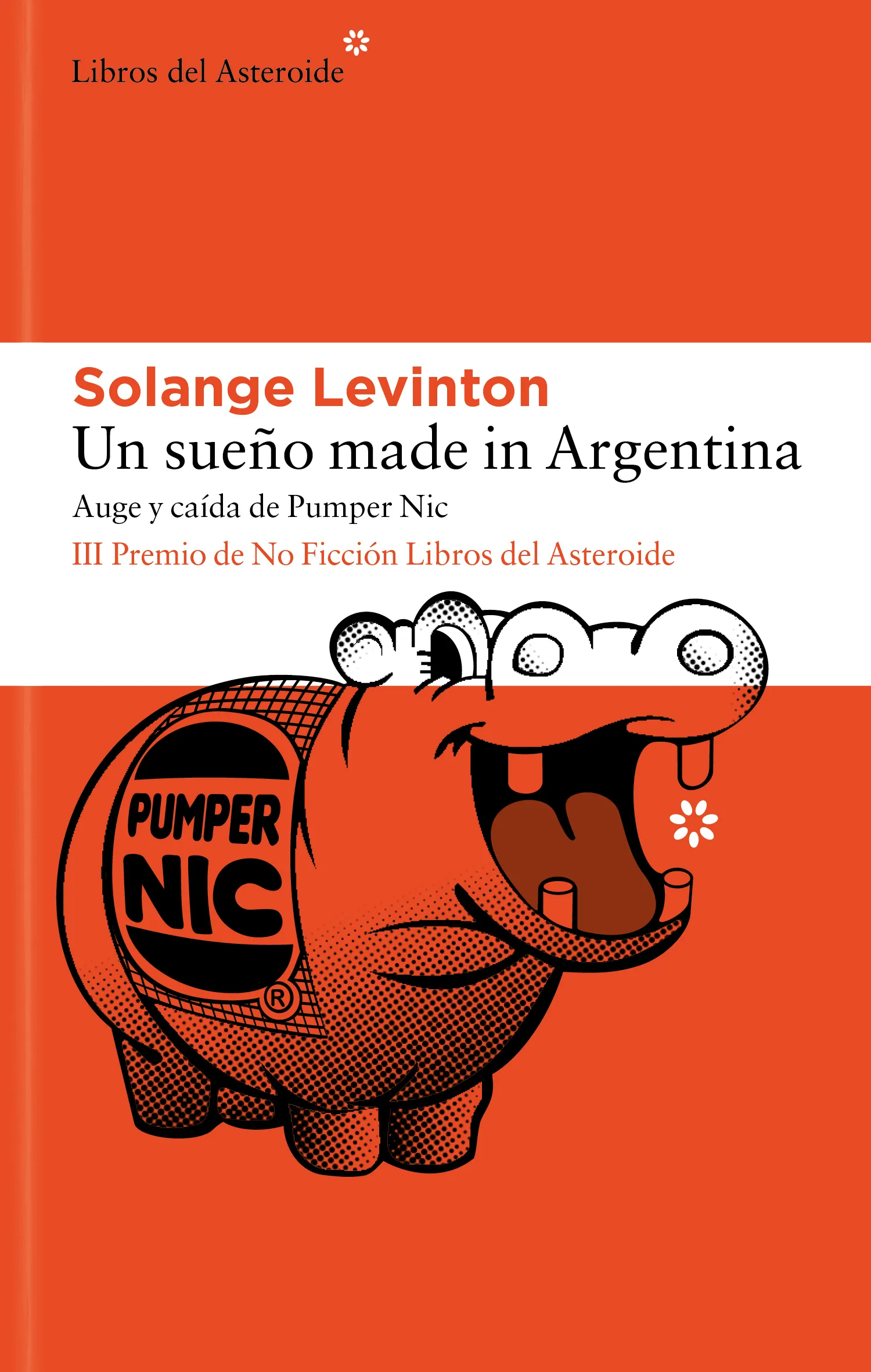

Solange Levinton was born in Buenos Aires, is 43 years old, and lives in Villa Ortúzar. She defines herself, above all, as a journalist: she worked for almost two decades at the Télam news agency, contributed to various media outlets, and trained in narrative journalism workshops. Although she says she feels more like a journalist than a writer, in March she published “A Dream Made in Argentina”, a book that reconstructs the history of Pumper Nic, the first fast food chain in the country. After two years of research, Levinton goes far beyond nostalgia: her work explores the connection between food and memory and paints a portrait of a time that speaks to culture, consumption, crisis, and desire.

About the book: A Dream Made in Argentina. What was the first thing that made you think: “There’s a story here”?

I think there were several things. The first spark came when, out of nowhere, I remembered that Pumper Nic had been the first fast food place in Argentina. It was where my grandmother used to take me, and that memory made me reflect on those lunches with her. The only thing I knew was that Pumper Nic had been the first, and I started wondering what that new way of eating must have meant for Buenos Aires society. Who brought it? How did Argentines learn to eat fast food? What was it like for the workers, for the customers? I started googling and found different threads, different facts, and realized there was a story there. I discovered the owner was Argentine, the company was Argentine, and the owner was the brother of the man who created the Paty hamburger brand... That’s when I understood it was a family of entrepreneurs. Also, I thought Pumper Nic was from the ’80s, but it actually opened in 1974, a very violent year in our history. That context caught my attention too. And the final push came when I realized it was a brand that evoked strong nostalgia for a lot of people. That made me want to dig deeper into the story behind the company.

“Pumper Nic was where my grandma used to take me, and that memory led me back to those lunches with her”

Beyond nostalgia, what do you think Pumper Nic says about us as a society in the ’80s and ’90s?

Pumper Nic says a lot. First, it reveals our eternal admiration for the foreign, especially anything American. There’s something about that which has always dazzled us. In the ’70s, when traveling to the U.S. was nearly impossible, Pumper Nic became our American portal just a block from the Obelisk. It also reflects that Argentine ability to make do with what’s available. We’re so used to living in crisis that it’s practically built into us. It forces us to be resourceful, to lean on a kind of street-smart cleverness (sometimes a good thing, sometimes not), but it helps us ride the wave. For example, when McDonald’s arrived in 1986, three years later hyperinflation hit. McDonald’s was in trouble. But Pumper Nic thrived, because they knew how to stock up, how to adjust prices, how to operate in an unpredictable economic environment. That crisis-adapted mindset says a lot about who we are.

“In the ’70s, Pumper Nic was our American portal just a block from the Obelisk”

In your interviews for the book, which testimony surprised you most or made you see Pumper Nic in a new light?

The one that surprised me most was with Diego, the eldest son of Alfredo Lowenstein, the creator of Pumper Nic. Diego was president of the company from 1991 to 1996. Until then, all the accounts I had gathered were about nostalgia, about memories of a place where many of us had been happy. He brought a different perspective: the business perspective. At first, it was hard to embrace, because business and emotional attachment often don’t go hand in hand. But he helped me understand why a family might let go of something that inspired so much affection. His testimony brought balance to the narrative. Without it, the book would have been just a string of lovely memories.

“Diego, the eldest son of the Pumper Nic founder, gave me the business perspective”

As a writer and journalist, what kinds of stories are you interested in telling today, in such a fast-paced, information-saturated world?

Honestly, I don’t know. Everything moves so fast now, everything is instant, and journalism is so precarious. It’s hard to take your time. The book took me two years of research, and that kind of time doesn’t exist in journalism today. I think I’m drawn to stories that make us think about something deeper when we tell them. For example, the way we eat also speaks to who we are. The story of Pumper Nic lets us think not just about a brand or a family of entrepreneurs, but about the context of a society—what it values, how it adapts. That’s what interests me: seeing what’s beyond the surface.

What dreams or projects do you have for the future? Another book, another urban myth to uncover?

I’d love to write another book, but right now I don’t have a topic I’m passionate enough about. It takes a lot of time, effort, headspace, and hours. And for that, you need to have certain aspects of life sorted out—which isn’t my case at the moment. But yes, I’d love to write another book. I just don’t know what it will be about yet.

FINAL RAPID-FIRE

One word to define the ’80s: Nostalgia.

McDonald’s or Pumper Nic?: Pumper Nic.

A journalist you admire: Leila Guerriero. Also Natalia Concina, a science journalist. And Paula Bistagnino, who wrote a book about Opus Dei.

Dream interview?: The creator of Pumper Nic, who never agreed to give interviews.

What food takes you straight back to childhood?: There’s a certain smell of burgers and fries that takes me back to those lunches with my grandmother—especially the mix of ketchup, onions, pickles. Or really, any traditional Jewish food.

A corner of Buenos Aires you love?: Plaza San Martín.

A book that left a mark on you as a reader?: I don’t have just one. But I’ve gone back several times to The Frog Hospital by Lorrie Moore—I’ve gifted it a lot too. I loved The Rachel Factor, and This Must Be the Place by Maggie O’Farrell.