The BFI London Film Festival – the biggest, brightest and best event in the capital’s film-going calendar – hits cinemas across the city from October 4-15 2017.

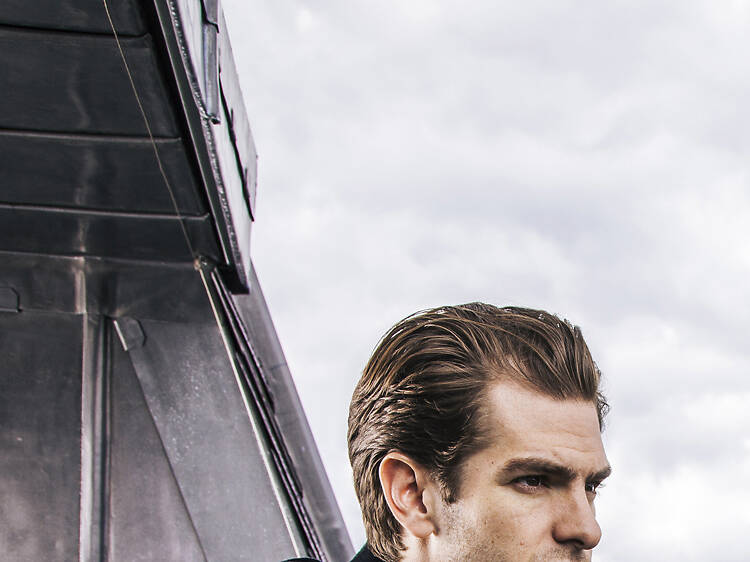

Andrew Garfield is spending an afternoon posing for us on a riverside rooftop, looking out over London like Spider-Man over New York. Except not. Because, while Garfield did a two-movie stint in the red-and-blue suit, he’s in a very different place right now.

Taking a break from the big screen (and jumping across rooftops in Lycra), the 34-year-old Oscar-nominated actor has just finished a lengthy run in the National Theatre production of ‘Angels in America’. Garfield played the lead in Tony Kushner’s two-part ‘gay fantasia’ about love, sex and the gay community in New York during the ’80s Aids crisis, rarely staged because of its epic eight-hour running time. Now he’s preparing to open the London Film Festival with his new movie ‘Breathe’. It’s the true story of paralysed polio sufferer Robin Cavendish, who, after being given only months to live at 28, defied medical opinion and survived into his sixties.

These are the latest in a long line of intense and compelling parts Garfield’s played. He’s pretty intense and compelling in real life, too. He gazes off into the distance when talking about something deep, which happens a lot. There are already whispers that he could be in line for another Oscar nomination for his performance in ‘Breathe’, but rather than focusing on clocking up Academy Awards, Garfield is insistent that he wants to make a meaningful impact (though he probably wouldn’t say no to a gold stauette, too).

‘I’d go and have a nap in the middle of the day in the cinema in Soho’

You’ve lived in London since you were 17. Do you feel like a Londoner?

‘Yes. My first job was at Starbucks in Golders Green. I auditioned around London a lot when I was starting out. I got an unlimited pass at Cineworld and in between auditions I would go and have a nap in the middle of the day in the cinema in Soho. There are only so many coffees I can drink to keep myself awake, so it was a really good investment, that unlimited pass.’

What do you like getting up to in the city now?

‘I haven’t had much time to absorb culture while doing “Angels in America”, but I just went and saw the Grayson Perry exhibition at the Serpentine, which I thought was so inspiring, deep, funny, irreverent and absurd. He’s such a brilliant artist. I also went swimming in Hampstead Ponds the other day, which was incredible. You feel close to nature – it’s such a rare, beautiful thing.’

How about eating out?

‘Barrafina is a favourite restaurant of mine, the tapas place. There’s a dessert – I forget what it’s called in Spanish – it’s like a loaf of brioche bread swimming in cream and milk, like dulce de leche, it’s so, so good.’

What attracted you to ‘Breathe’?

‘I got to tell a true story about the best of what we’re capable of as human beings: creating a community, taking care of each other and fighting for rights. Robin built a bridge between the disabled community and the non-disabled community, and reminded us we all deserve to live full and rich lives no matter what circumstances we live in.’

‘I feel very privileged to have done “Angels in America”’

Director Andy Serkis told me that you wore dentures in the film moulded from Robin’s son Jonathan’s teeth. Why?

‘Robin had large, prominent upper teeth and Jonathan shares that with his dad. It did something different to my mouth and my voice, and it did something different to my psyche.’

What about the challenge of playing someone who was paralysed?

‘I had to go as deep into the experience as possible and portray it with as much truth as possible. I’m never going to be able to fully understand what that is, but my job meant empathising as much as I could.’

How was ‘Angels in America’? It must have been exhausting.

‘Hard to complain about it. It’s sadly very pertinent to the political climate. So I feel very privileged to have done it.’

Has doing the play made you more passionate about LGBT+ rights?

‘It’s deepened my longing to get the world to where we want it, in terms of how we treat each other. The fact that certain communities have to fight for equality to be treated as the divine creatures they are: that is outrageous.’

‘We’re in a time now when most of our connection is done through our technological devices’

You wrote a letter for Time Out’s 2016 Pride issue after the Orlando shooting. Thank you for that.

‘It was a pleasure and a privilege to have a voice in that moment after the Orlando shooting. I felt I wanted to do something. It was a small token from the heart. I was very grateful to be asked.’

In it, you wrote about connecting with strangers. Do you feel strongly about that?

‘We’re in a time now when most of our connection is done through our technological devices but the deepest connection happens when we are in the same room. Doing this play, with not even a film screen between audience and performers, feels like the most profound connection you could ever hope for.’

Were you this intense as a kid?

‘As a teenager I was very analytical, but when I was a kid I was a clown, and it was bliss, it was bliss… [looks wistful] Then you wake up, and you get hurt, and you have to understand what life actually is. You don’t just get to play the fool.’

Were you the class clown?

‘Yes, definitely. I would get into trouble a lot. My place within the structure of school was to subvert everything. But then I had my first ever theatre experience when I was 15. I saw Simon McBurney in Theatre Complicite doing “Mnemonic”. It was the first time I was in a theatre outside of, you know, panto and Punch & Judy. I sat there and thought: This is worth me being very, very attentive. It was the first time I felt like I was in a classroom, in a real way.’

‘This is a really sick time in Western civilisation’

Properly learning, you mean?

‘Absolutely. It was like I was on the hallucinogenic drug ayahuasca. The walls of perception just melted. I felt a sense of some destiny waking up. I think we all get opportunities for that, it’s up to us whether we listen.’

Do you actively seek out profound movie roles?

‘I’m looking for things that are challenging and give something meaningful to the audience.

If I can look at the majority of things I’ve done and say that’s the case, that makes me happy because I know that my heart’s in every one of them.’

How do you square that with the glitzy side of Hollywood?

‘I don’t feel like I’m in that world. I have my life, I have my friends, I have my family, I have people who I am sincerely close to. The rest is a vehicle to get stories out there. I think celebrity culture is distancing. It keeps people on pedestals and that doesn’t feel healthy for the culture right now. I don’t know if we need movie stars any more.’

But we do need movies, right?

‘What I’m looking for when I step into the cinema is a reminder of what’s important and what’s meaningful in life. Human life is so disposable now. Look at what is happening in our city with Grenfell Tower: the people who are making decisions value money-saving over keeping people safe. This is a really sick time in Western civilisation, so I’m looking to be part of feeding an audience and a culture with something that thinks to bring us back together.’

‘Breathe’ opens the BFI London Film Festival on Oct 4 and is in cinemas from Oct 27.