Rice

Japan’s staple grain has played a starring role in Osaka’s history, both as a foodstuff and, even more importantly, as a medium of economic exchange. Rice has been used as a means of tax payment in Japan since ancient times, but it was in the Edo period (1603–1867) that the country’s economy became truly rice-centric. Not only taxes, but the salaries of the entire samurai class were paid in rice. Trade in rice, and its exchange for cash, became key economic functions – both of which were centred on Osaka, the country’s main mercantile hub.

Prices at the government-sanctioned rice exchange in Dojima determined the value of the grain nationwide, and many of Osaka’s rice brokers – the middlemen who greased the wheels of commerce – made fortunes much in the same manner as today’s stock traders. The rice-based economy didn’t only enrich merchants, however: it made the grain widely available across society, fostering a distinctive culinary culture.

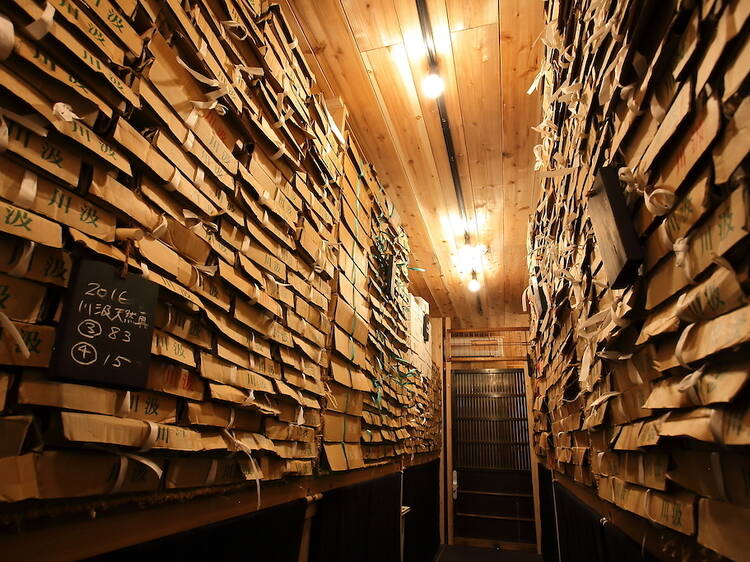

The Dojima Rice Exchange is long gone, its site now marked by a monument designed by architect Tadao Ando in the shape of a grain of rice. The prosperity and splendour engendered by the rice trade can, however, be felt at the historic granaries of the Konoike Shinden Kaisho in Higashi-Osaka, built in the early 1700s by a wealthy merchant to expand rice production to the east of the city.