By Hajime Oishi

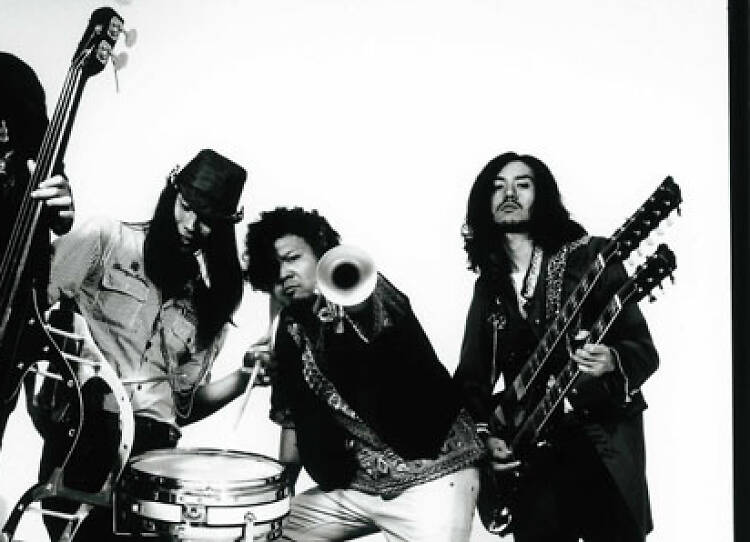

Standing in a rain-lashed pool of mud seldom felt better than on the Friday night of this year's Fuji Rock Festival, when Asakusa Jinta played to a capacity crowd at the cramped Naeba Shokudo stage. After a day of craptastic weather crowned by a Coldplay set, the Tokyo sextet came on like an aural adrenaline shot, combining swing, rockabilly, klezmer, punk and gypsy music into a wild, mosh-inducing mix. It's a trick that has won the group a fair few overseas admirers, and they've toured Europe as well as playing twice at the prestigious SXSW festival in Austin, Texas. Earlier in the summer – on the traditional festival of Tanabata, no less – they released their fourth full-length album, Yamiyo de Danse (literally, 'dance in the dark night'). The band's leader, vocalist and double bassist Oshow, tells Time Out that he'd pondered what message he was trying to get across with the record, and eventually realised that the answer was quite simple: 'Don't give an inch.' He talks to Hajime Oishi about getting beaten up in Memphis, and how Asakusa Jinta are actually a lot like sake.

Were you born in Asakusa?

No, this is where I ended up drifting. I've been based here for about 14 years now. I was born in Setagaya and moved around a lot in Tokyo, and I'd been listening to punk, rockabilly and 'world mixture' music like Mano Negra for a long time. When I decided to make music myself, I thought I should choose a base, and it was a toss-up between New York and Asakusa. At that time, there weren't any new, fresh sounds coming out of Asakusa – in Okinawa or Kyoto, sure, but not in Asakusa. That's what made me decide to do it here.

I had a formative experience when I went on holiday to the States, too. I was a rockabilly, so I went to Memphis dressed in my rockabilly gear, and I got my ass kicked. People were taunting me, like, 'Oi, rockabilly boy!' and I ended up with a broken nose. (Laughs) It was a rough experience, but when I got back I thought, 'I'm giving up English.' That sense became the basis of what I was doing.

Did you experience any difficulties, basing yourself in a place with as much history as Asakusa?

Well, I thought that's exactly why I should do it. For example, making a big deal about being Japanese in New York means nothing compared to doing it in a place like Asakusa that's right at the heart of Japan. When we started getting supported by local people, I felt, 'This is turning into real world music.' That's one mountain which is worth climbing.

'Jinta' refers to a kind of musical group that's been around since the Meiji Period, but there are elements of klezmer and gypsy music in Asakusa Jinta's sound, too. How did you conceive things musically when you were first starting out?

I feel there are commonalities between the Japanese scale and, for instance, the klezmer scale. If you strip away the rest of it you can see them as having the same stem. It's not like I'm having to do everything myself: there's already a core there. All I'm doing is finding the common ground with [klezmer and gypsy music and] the Japanese sense of blues, swing or shuffle, and with Japanese melodies.

Yes, you can definitely feel the similarities between Japanese music and klezmer. There are some melodies that give a real sense of nostalgia.

Japanese people really like gypsy music, right? I think it's something they feel unconsciously. You get the same thing with reggae and enka. There are lots of examples.

So it's not like you were doing lab experiments to find out what happened when you combined klezmer and gypsy music with punk or ska – it was more natural than that...

I want it to be something that just ended up that way. Even [Korean techno-trot singer] E-Pak-Sa must have started out meaning to make straight-up techno, but then he realised he'd ended up with something different. (Laughs)

There's a lot of talk about 'global' and 'local' on the Asakusa Jinta website. Can you tell me a bit about that?

Simply put, it's like selling locally produced sake around the world, or circulating it internationally. I think if you spread something that local people make, support or respect around the world, it has all kinds of knock-on effects. In that respect, we're like a kind of locally produced sake.

Asakusa Jinta are like jizake...

Yes, that's the root of what we do.

Yamiyo de Danse was recorded after the earthquake, but did that have any effect on the album?

It did. My views of our music changed. Everyone was very down after the earthquake, so I thought I should sing something to cheer them up, but what we really needed was something that would make them stronger. If there's something you want to say, say it. If someone's an idiot, tell them – I thought that's what mattered. For example, the title Yamiyo de Danse was originally based on the idea of dancing in the darkness, but now the nuance has become 'Let's keep dancing until the dawn comes.' You could say that's a result of the earthquake.

How was it different musically?

Before now, the band had a principle of not using a click track when recording, but this time there were things we wanted to do so we decided to use one. It's odd that it ended up having such a live feel.

What made you decide to use a click track?

I thought we should try and do some remixes. I felt that if we just worked within the limits of the Japanese rock scene, that would impose boundaries on what we were doing. For instance, there's the J-rock corner in the record shop… but one time, we ended up in the rakugo corner. (Laughs) Even the shop staff weren't sure where we should go.