Read the full review of Gone Girl

The most important scene of David Fincher’s still-blooming career—circa 2007—takes place in a cafeteria, one of those sickly green industrial spaces the filmmaker has always preferred. The movie is Zodiac, a spooky history of late-’60s, serial-killer–inspired panic in San Francisco. Pulling up some plastic chairs, three cops take a seat. Before them is a suspect, Arthur (the unsettling John Carroll Lynch), who returns their stare. Gallingly, he wears a wristwatch displaying the murderer’s self-styled logo. “I am not the Zodiac,” Arthur flatly states. “And if I were, I certainly wouldn’t tell you.” And in the space between what we think we know and what hides in plain sight lies the career of cinema’s reigning deceiver.

“I hope it’s not as easy as that,” Fincher says, countering a question—one he’s asked often—about his penchant for devious behavior. “Will I ever make another movie with a serial killer? I never say never. I’m not looking for that. But I’m also not looking to avoid it.”

Let’s take him at his word. He’s too busy working on the increasingly substantial films that have kicked him up more than a notch, from video-whiz-made-good to critical darling and king of pain. Calling us from a Stockholm hotel, the 52-year-old creator ofSeven, Fight Club, The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is in a playful mood, one that keeps him on the phone for nearly two hours.

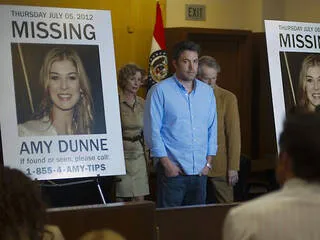

Our main topic is Gone Girl, Gillian Flynn’s electrifying 2012 mystery novel that you’ve seen everyone toting around—and hopefully not spoiling. The book is about to become a David Fincher release, and the match is a perfect one. World-premiering in this week’s prestigious opening-night slot of the New York Film Festival, the movie brings voluptuous cool to Flynn’s scenario—an urbane young wife goes missing and her husband becomes the chief suspect in a televised media circus—while giving Fincher plenty of marital psychology to explore, as he has on Netflix’s House of Cards, a show he produces. (Making history, Fincher became the streaming service’s first Emmy winner last year.)

You’re going to have to help me out here, because I don’t want to spoil anything. Happy marriage doesn’t seem like a subject you’d be interested in, and clearly Gone Girl’s not about one either.

I was looking for something I’d never seen before. The book talked about narcissism in a really interesting way—the way we concoct not only an ideal version of ourselves in hopes of seducing a mate, but in hopes of seducing someone who is probably doing the same thing. [Laughs] Gillian was looking at what it is that erodes the foundation of marriage.

The book reads like a satire of marriage, a marriage that only two very savvy self-aware people could have. Gillian Flynn also wrote your script.

Gillian is astutely aware of what it is that she’s doing. At the same time, she’s a popcorn-munching, sitting-in-the-third-row, craning-her-neck movie fan. The fact that she had written this elaborately marbled novel initially gave us all pause: You know, would she be able to slaughter her darlings? But she didn’t just tree-trim—it was a deforestation! She could come in and remove anything that wasn’t working. And this is what initially got so blown out of proportion with Entertainment Weekly, this notion that she had concocted a whole new third act. It was still ostensibly the same thing, just attacked from a completely different vantage.

She’s a deadline writer. She understands that.

There’s obviously a corn-fed Midwestern work ethic there. [Laughs] She really understood when I would say to her, “It doesn’t matter what we want it to be, if you can’t get that from the playing.” That’s what dramatization is.

For a debut script, it’s very impressive. Meanwhile, you’ve never taken a writer’s credit on any of your movies.

Because I don’t write.

But it sounds like your collaborations are very close.

I’m a really good collaborator as a director, but I’m not a writer. I feel like writing is way too difficult for people to say: “Hey, I was the one who decided this should be a contraction.” That’s not authorship. When an actor says, “I have a better way to say this,” I don’t consider them a card-carrying member of the WGA. I consider them an actor doing what the fuck they’re supposed to do.

So would you say the job of a director is interpretive?

It’s adaptive. You’re doing an adaptation. You’re saying, “I understand what you mean on the page.” And you’re moving around tectonic elements that already exist in a novel that [Gillian’s] done an inordinate amount of thinking about.

Let’s talk about Amy Elliott Dunne, because she’s such a fascinating character, a perfect ghost. Her legend looms over the film—even over her own life through her parents’ “Amazing Amy” books. She dwarfs all the characters in her absence. Gone Girl feels a little like an obsession movie, like Lolita.

She’s the sun of the film’s solar system. We talked about Lolita. But in a weird way, it was when we were trying to figure out who would play [Amy’s creep ex-boyfriend] Desi. I started talking about Lolita’s Clare Quilty, because these are characters whose feet don’t touch the floor. They’re not of the real world. Desi’s a collector.

Talk to me about actor Rosamund Pike. She’s stellar.

I was looking for a certain opacity. The thing I loved about Rosamund was that I literally had no idea how old she was. I had seen An Education. I thought she could be twenty-two. She could be forty-two. And I sort of had this idea of [John F. Kennedy Jr.’s wife] Carolyn Bessette. I wanted the ultimate trophy wife for a well-intentioned would-be intellectual.

How much of Amy—especially in your casting of Rosamund—has to imprint on us visually, without us really knowing her?

Exactly. You can’t know her. It’s what we talked about when we started casting House of Cards. There were a lot of people saying, “Ah, so this relationship between Francis and Claire is Bill and Hillary [Clinton].” And I said, “No, it’s definitely not.” It has to be unfathomable. I wanted Amy to be this put-together creation. I needed something from Rosamund that she couldn’t play. No matter how much I wanted to be able to talk about this quality, it had to be there at the 18th hour of the day, when everybody is completely exhausted and you can’t beat it out of them with a stick: I needed the only child. So I met her and I said, “So tell me about your siblings.” And she said, “I’m an only child.” Of course, I went: ding!

Ben Affleck is also ideally cast. How much of his iconography came into play? There’s a prettiness to Nick, almost a preening quality.

Well, we definitely pushed that. Here’s the thing people don’t know about Ben Affleck: He’s way smart. He can be mean and bitchy. And he is a formidable intellect. He chooses—because I think there’s the actor side of him that wants to be liked¬—to let other people off the hook. But it was his intellect and the fact that he truly understands what a shit show it is to be scrutinized in the paparazzi 24 hours a day—he’s been through the whole Bennifer thing. He knows the cosmic joke of it, which is: You can’t spin this. You’re not even in it.

This idea of playing the media—or getting played by it—is threaded through many of your films, not just Gone Girl and The Social Network, but as far back as Seven. I wonder if you’re scared by the power of the media.

I don’t know that I see it as a source for good any longer. I can’t say that when I go to get my teeth cleaned, I don’t pick up a People magazine. I’m not above that. But I don’t think the media in Gone Girl is the antagonist. It’s there to complicate the story. I’m talking about the people who are saying, “We’ve got to have a scandal. We have to have something happening.” That’s an animal you can’t prepare for.

Or tame.

It’s like message boards. You don’t want to engage—you don’t want to go there. It’s like a second grader going: “I don’t like your shoes.” What do I care? You’re in second grade. What difference does it make? You’re entitled to your opinion. But I’m really not going to go home and change.

That’s what a grown-up would do.

It’s hard!

What about this whole celebrity-nude-photo thing?

As somebody who’s never wanted to take picture of himself naked, the impetus to generate the material is beyond me. But Gillian Flynn is interested in that stuff. She’s interested in earnest God-fearing people who are curious as to what’s happening in the house at the end of the cul-de-sac where the shades are drawn. And she’s figured out a way to talk about what goes on in that bedroom, by segmenting the house and filleting the participants. Hats off to her, because it’s a great combination of highbrow and lowbrow.

That’s the sweet spot, right?

Oh, I agree.

Especially after The Social Network, you were launched into a place of Oscar nominations and critical guild awards. Are awards important to you?

It’s totally dishonest to say that one doesn’t appreciate acknowledgment from people who know how difficult it is to do this stuff. But we’re not curing cancer. We’re just hopefully making entertainment and if we can elevate it, even a little bit, that’s all good. But it’s tricky. Would I rather spend my time doing something else than sitting uncomfortably sweating in a tuxedo, being scrutinized for my gratitude? Yeah, there are a lot of other ways that one can spend four hours of one’s life that don’t cause you the same dyspepsia.

How do you handle that personal attention?

There are very few things as collaborative as the making of a film. Hollywood is culpable for having creating the mythology that everything is done to very exacting standards, and nobody makes a move forward without knowing the effect. But the fact of the matter is, it’s more like couture fashion: You’re making a one-off. And it’s got to go down the runway and enough people have to clap and take a picture of it, and sell a $100 million worth of tickets.

Going from the large scale to the small, I’m a huge fan of your music videos. Some of them are now considered classic. Has making them affected your aesthetic?

It comes from wherever you’re raised. I didn’t go to film school. MTV was my film school. Instead of having to pay $30,000 a year for a master's degree in directing, I got to get paid and try a lot of stuff out. Remember, when I started, the promise was: Don’t worry, your name’s not going to be on it. I wanted to play. And I wanted to learn from my own mistakes. I’m working on television show right now about this very phenomenon: 22-year-olds were getting awarded a song and a budget on a Monday, shooting the video by that weekend and then postproducing on the next weekend. Two weeks later, it was on TV.

It sounds exhilarating.

Exhausting and exhilarating. I don’t think you will ever see another multinational media conglomerate get out of the way of what a 22-year-old wants to say about whatever—and then put that shit on the air, 24 hours a day, to be pounded into the cerebellums of people hungry for a new cultural outlet. I don’t think that that will ever happen again. When you’re making a music video, the person that you’re shooting the close-up of is paying for it. Not the record company. Record companies pretended they were paying for it, but it was really coming out of royalties. I was always very sensitive to that. The people that I worked with were investing in me, and at the same time, I was investing in them. I wanted them to look good—and I’m not just talking about cosmetically. I wanted this investment to seem smart. I didn’t work with very many people I didn’t have respect for.

When you’re talking about Madonna’s “Express Yourself” video, you’re talking about an essential piece of the legend. You’re delivering her persona—some might say you’re making the persona.

That whole thing began with her saying to me, “You know [Fritz Lang’s] Metropolis?” Yeah, I know Metropolis. [Laughs] I was like: Back off, man. We’re doctors. It was a very interesting time and place, and I’m not Mr. Nostalgia. It was truly the inmates running the asylum. And a lot of people got rich—I wasn’t one of them.

You continue to have an affinity for music and musicians. Gone Girl’s score composers, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, seem to understand your intent very well. How does that collaboration work?

I played them a two-hour-and-50-minute version first cut of the movie. Afterward, we walked outside. And Trent was smiling—Atticus never smiles, but Trent was, which is never a good thing because he only smiles when he’s getting away with something. He’s a little incorrigible in that way. So I said, “What did you think?” He goes, “That’s nasty—that movie is mean!” I thought, Good, good.

They also did The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. You must give them specific notes about what you’re going for, tonally.

I said, “I want you to give me your version of spa music. These sort of endless loops that play when you’re getting a shiatsu. Because I know it’ll be disquieting. And I know it’ll take root somewhere in my spine and upset me for weeks on end.” My movie is about the good husband, the good wife, the good neighbor, the good Christian, the good American, the good patriot. I want music that’s there to soothe and assuage. And that’s what they came back with.

You must be aware of your reputation as a perfectionist. Is that something you’re defensive about?

I’m defensive about the word perfectionist, because I think it’s bandied around, like when people say edgy. They’re too fucking lazy to actually come up with a real word.Perfectionist is a polite way of saying compulsive. And I don’t think I’m a perfectionist. That’s a term people use who have no idea how movies get made. This is a ballet with no rehearsal. You can’t rehearse a shoot. You have to come in on the day and perform that dance. And there are so many things that can come between you and the intent.

Did you experience that on the Gone Girl set?

When Tyler Perry showed up, he was like: “Are you kidding? We’re going to do another one? Why?” We’re not doing another one because anything was wrong. We’re doing another one because I think that there’s a mistake that will be made—somewhere down the line once everyone gets bored—that will be more like human behavior than everything being offering up now. If I can get you as an actor to forget your real middle name, I think you’re going to stumble onto something that’s going to make you go: Oh! It’s always the best take when an actor starts falling face-first.

Do you find you have that conversation with actors frequently?

Yeah. All the time. Look at the role Ben Affleck is playing in this movie. Nobody signs up to have their scrotum put in a vice at the beginning, right after the Fox logo. And then watch it get tightened for two hours. You have to be pretty confident in yourself to go through what Nick Dunne goes through.

People will be surprised to see Tyler Perry in this.

I love him. He's a guy I went out of my way to talk into being in this movie. I met him when I was in Atlanta looking for soundstages for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. He has a huge campus with seven or eight soundstages. As we walked up to the main building, I saw this guy on the roof, in a tracksuit with a radio-controlled airplane. He was flying it around in circles. Someone then said to us, “Mr. Perry will be right with you.” I thought, That’s who Tanner Bolt should be. He’s the guy who puts you on hold while he finishes flying his remote-controlled airplane.

Was it your idea to kind of make him kind of a Johnnie Cochran figure?

He’s painted as a shyster in the book and I didn’t think I had room for that. I needed somebody who’s like a talk-show host, who can put you at ease. Tyler has an amazing voice. And he makes eye contact with you—he listens to you. He’s genuinely interested in what other people have to say. And the part was kind of written as this sort of Alec Baldwin smoothie. I didn’t want him to be glib.

How do you feel when people use the term Fincheresque? Have you heard that?

I’ve heard it in jest.

Do other filmmakers loom in your head at this point?

I was probably in my forties when I first became comfortable. I started directing when I was 21. Let’s put it this way: I don’t trust anybody who doesn’t go to bed at night feeling like a fraud. Feeling like: Tomorrow is the day I get the call and they rescind my ability to do this thing that I love so much that I would do it for free. There’s a part of you that is always waiting to be found out—especially when your job is to walk into a gigantic room with 90 people staring at you slack-jawed saying, “What do you want to do next?” Before I could even walk on a stage, I had to go throw up. And then you walk out and you do the best you can to look like you’re in charge.

Your early movies were hard births. Now how does it work, 30 years down the line?

I didn’t have a great experience the first two times with Twentieth Century Fox. On my first movie [Alien3], I was expecting a collaboration. And I don’t feel that way now. I feel like I’m hired to make a movie. And on Gone Girl, we got to make exactly what we wanted. I’m very honest about the movie I intend to make. I talk about that stuff in advance. I want the people who are paying for the film I’m lucky enough to make to understand, because you are managing expectations. That was something that I didn’t have coming out of music videos. I had it in a three-and-a-half-minute envelope, I didn’t have it in a two-and-a-half-hour envelope.

Are surprised with where you are now in your filmmaking?

Not when you watch rushes, because you’ve been through 30 meetings about: What is the effect of this necktie? And why would he wear a watch like that? And the blood isn’t going to be on any clothing, it’s going to be on skin, so it can’t be so translucent. You’ve had all these discussions, so no—you shouldn’t be surprised.

Maybe more generally, then, with your art.

I always find that when it’s very clean and clear, when we can articulate it well and everybody gets on the same page, it causes me a real sigh of relief, because you say, “All this hard work can actually make something the way we all talked about it.” And that’s… [Whistles appreciatively] If that didn’t happen ever, you would just want to shoot yourself in the face. But then there are times when the weather’s fucking horrible, the dolly grip took the wrong exit and is 45 minutes late, and you get off to a bad start. And you sit there and you hammer at the scene and you try to make it better, more deft, more witty. Yeah, if you were putting as much time and effort into answering all those questions and were ending up with a product that bore no resemblance to what you were trying to accomplish, it would be incredibly depressing.

Gone Girl screens at the New York Film Festival Fri 26 and opens Oct 3.