You’re among those who have witnessed and survived the Siege of Sarajevo in the ’90s. As someone who was in her teens at the time, how do you think those tragic memories affected your evolution as an artist?

“Each artist draws from his or her own experience, and every big life event defines us. I was studying art before the war started and back then I thought that art was the most important thing. When the war started, I had to grow up very fast, and I learned, in the most brutal way, the order of the essentials we really need to survive. One of these is freedom. Through art, we fight for freedom in a very special way, and even when it is denied we create spiritual freedom that nobody can take away.”

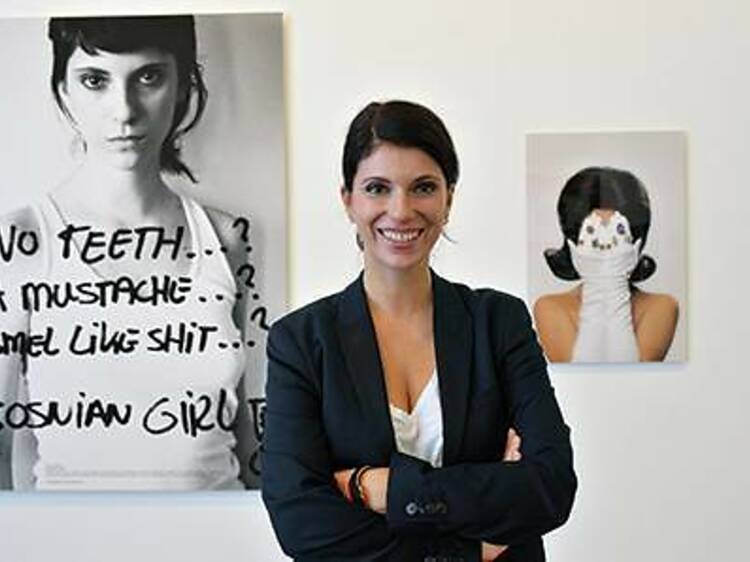

What’s the story behind your famous piece Bosnian Girl?

“This work was made in 2003 as a public project in the form of posters, postcards, magazine ads, etc. It was a very direct and straightforward reaction to what I felt when I saw a graffiti made by a Dutch UN soldier in Srebrenica. I use my own image not just to portray myself but to show that I can accept any perception imposed by others. I’m a ‘Bosnian Girl,’ and only I could put myself in the position of the ‘Bosnian Girl’ described in that graffiti. I also wanted to say that we are all victims and perpetrators. And the prejudice is just self-reflection.”

Your works underscore that the delicate and sublime cannot be pushed aside during times of hardship; they insist on the tenacity of the human spirit. What would you like to tell the people of Turkey during this difficult era?

“Unfortunately, we live in a world that is in a permanent state of war. It is just a question of how far the battlefield is from our home and how aware we are of what’s happening around us. I believe that we often forget a very simple and extremely important fact: each of us has the power to change things. We have to be active and responsible and make the world a better place.”

What triggers you to use your own image in your works?

“Sometimes I use my own image without the intention of making a self-portrait, but at the same time, all my works can be seen as self-portraits. The starting point is inevitably the individual. In the creative process I insist on experiencing all the emotions, ideas and roles that the topics I’m working on bring about. I focus on different ideas through different media. My own image and my own body are often just a tool to realize an idea.”

The production process for your work Ab uno disce omnes (“from one, learn all”) was driven by the important role forensics played in the investigation of war crimes and missing people after the Bosnian War. The work also put considerable pressure on governments to make the location of mass graves and missing person lists public. How did you make that happen?

“This project was commissioned by the Wellcome Collection for the exhibition Forensics: Anatomy of Crime in London. The work is rooted in my acute interest in forensic medicine’s integral role in Bosnian society in the wake of the Bosnian War, and it addresses the brutal legacy of the past. The whole process took two years and included field research and visits to mortuaries, DNA laboratories, commemoration funerals, places of atrocities and crimes. During this process we also worked in collaboration with regional and international institutions as well as family members of the missing persons, and survivors of the concentration camps. I can proudly state that thanks to Ab uno disce omnes, we managed to release all existing lists of missing persons in Bosnia; we also made a list of mass graves and put pressure on the authorities and some organizations to make public their information pertaining to the location of these sites. We now have a list of more than 5,000 gravesites, including the mass graves, with their coordinates and maps. We also have a list of concentration camps and all of that has now become public information. It can be found on abunodisceomnes.wellcomecollection.org.”

The pink line you drew on the Nicosia border separating Turkish Cypriots from Greek Cypriots was erased in 2005 per the mayor’s order. How do you feel about coming back to Turkey after this event?

“The work you’re referring to is a public project I did in Cyprus titled Pink Line VS Green Line. In one way this work was a reaction to the political mindset in which the border is called a Green Line and discussion about it is not welcomed. We did not have the permission to do this work; it was more of a guerrilla-style action. In addition to the pink line that was painted on the wall of the Green Line I also did a graffiti that read ‘There is no border, no border, I wish.’ The very next day, the lines were repainted, first with white then with gray. This kind of naïve censorship was expected and even amusing to see. But the graffiti stayed untouched, and now, ten years later, I wonder if it’s still there. Unfortunately, Nicosia is still a divided city. Walls are being built on borders all over the world, and people are dying trying to cross them. It is hard to predict what will happen next…”