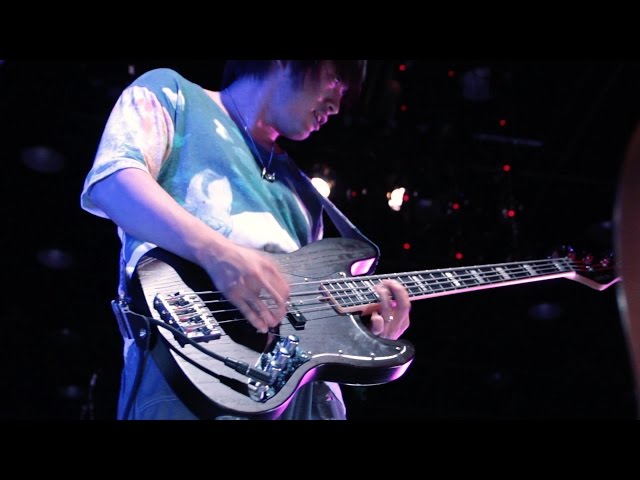

Often classified as a math rock band, four-man outfit Lite was formed in 2003, when post-rock was still in its infancy on these shores. Only three years later they were touring the UK, and today Nobuyuki Takeda and Atsushi Izawa's crew rank among Japan’s finest instrumental rock bands.

Distinguished by their rare career path, which took them overseas early – something that appears to have been vital to the longevity of the band and a wellspring for their creativity – Lite released Cubic, their fifth studio album, in November last year. Drawing on wild touring experiences, the album marks a shift from the miniaturised soundscapes of their past work to a more approachable, open sound. Currently in the midst of a nationwide tour, the boys behind Lite took time out of their busy schedule to talk influences, future plans and why heading overseas has been so crucial to their success.

My impression is that Cubic has a completely new, expansive sound compared to your previous work.

Nobuyuki Takeda (guitar): It was created on computers. Back in the day, we would build up our tracks and then remove bits. If we had four guitar players in the studio version, doing that live wasn’t possible. So this time we decided to start from a minimalistic approach and slowly add bits to create a tight and clean sound. The production really gives you the feel of a soundscape, we hope.

Atsushi Izawa (bass): In terms of mixing, so far we had focused on a sharp and bold sound, but this time our idea was to give the music depth. This might be why it sounds more lush. So rather than building up the sound, we keep it hushed in parts. The approach is totally different from last time.

Tracks like ‘Inside the Silence’ and ‘Blackbox’ act as a kind of interlude on Cubic. Given that many listeners today download individual tracks or listen to them as standalone singles, did you structure the tracks as part of a bigger whole because you want to argue for the album format?

T: That’s right. One track isn’t enough for a gig, after all. You have a flow, and that gives the tracks appeal. I think albums need a flow to them, too.

I: Once you have several tracks, you can then think about the order you want them to appear in. You talk about gently leading into a drum beat, or how many seconds to leave in between songs, whether we should add a song with no beat in between and so on. That thinking then leads to building new tracks. So the flow of songs on an album is really important.

T: I think the songs work together, they interact. We also think about how to make tracks stand out.

I: In that sense, streaming services like Spotify kind of miss the point of what we are trying to do.

T: It’s a shame, but this really makes playing gigs worth it. If you go to a gig, you aren’t hearing the songs loose and unconnected – it’s much more powerful, I think.

The track ‘Warp’ is the first one Takeda sings on. Why did you choose to sing in Japanese? Since your focus is on instrumentals, wouldn’t English be better in terms of bringing your music overseas?

T: Even abroad, where we finally are getting recognised, we are considered a ‘Japanese band’. In Japan, there are bands that have sort of developed independently from the trends in the rest of the world – we are one of them. Therefore, we actually think it’s better to emphasise those aspects and see what kind of reaction we’ll get.

Some artists switch to English when going overseas. You opted against that?

T: The more we go overseas, the more we feel there are limitations to Japanese artists trying to sing in English. We often hear locals say things like, ‘Why are those guys singing in English?’ or ‘Do you call that English?’

You’ve toured quite a bit in the US. Which part of that country works best for you?

I: Definitely the East Coast. This also seems to be the case in Japan, but our music tends to resonate with people in urban contexts. When we go overseas, checking sister cities against those in Japan gives you a sense of how the fanbase and reaction is. So if we go to San Diego, we would compare that to Yokohama [laughs]. And in fact, the response seems to be similar to that you would get in Yokohama.

In Japan, post-rock fans tend to be pretty serious – nerdy, even. How are things in the West?

I: That aspect is really different – there were lots of kids in our audience in England, in particular. They would mosh pit and dive during our tracks, go kind of crazy.

T: They also chanted some of the lyrics. After touring the US, we found that to be the case there, too. If you think about it, Japanese listeners are quite unique. Japanese fans are really serious about just listening to the show.

There doesn’t seem to be much stage-diving at Lite’s shows in Japan.

T: None whatsoever! [laughs]

I: It’s not that Japanese listeners are boring or anything, not at all. We, too, listen to music that way. There are people who listen to music not in order to dance or let loose, but just to take in the tunes.

In terms of your reception in other Asian countries, you don’t really have a blueprint for promotion. How did your tour of China come about, and what was it like to perform in a place where your work hasn’t even been released?

T: There’s a Belgian guy in China who invited Mogwai, Battles and other artists out there, and he invited us too. [The experience] was super strange. We were amazed to discover that there were so many people slipping past China’s firewalls and all that and listening to our music.

I: They can’t access YouTube, Twitter or Facebook. They can only see that stuff by going through servers in other countries. The same is true of them trying to pitch their own stuff overseas. So the fans are really earnest. It’s amazing to think that our fans are people who are digging deep through the forest of data to find us, a Japanese band, and then deciding to go see our shows. It’s almost like back in the day, when you might pick up a CD and learn about a band through the liner notes.

They’re in a context where they can’t just passively come across that info.

T: That’s right. If you don’t dig, you won’t find it.

I: Our general impression of what they consider underground music there is the Japanese post-rock scene, that sort of thing. And things like anime songs. It was those two extremes, in our impression. The guitar rock style of music that’s popular in Japan is still not very well-known there, it seems. Those who have come before us, like World's End Girlfriend and Toe, have taken the lead in going to Asia – they played a major role in opening up these fanbases.

Do you have any strategies for promoting your overseas tours?

T: It sounds simple, but there are still few Japanese artists who really pitch their work in English. They focus only on their website, or Facebook, or Twitter. In our case, our Facebook page gets the most hits from people overseas, so just posting in English really brings different results, we found.

I: If you’re doing a show in Osaka, all you have to do is write the city name in English instead of Japanese, and people seem to notice. But bands often don’t.

What do you do for other Asian countries, then?

T: In both the West and Asia, people who really know the scene have invited us out there, and they get people to come to the shows. Therefore, you have to be known, in addition to promoting yourself in English, to the same extent you are in Japan. In Asia, maintaining both of those things is really important.

I: That’s right. Our sense is that in Asia, if you do well in Japan, people will generally pick that up and respond to it elsewhere.

Takeda, I hear you’ve also been involved in lining up gig spots and the like. Apparently there’s a system for Japanese bands to receive subsidies from the government when going on tours overseas?

T: That’s right. As part of the Cool Japan project, the government provides artists with funding to promote their stuff overseas. If the work involves promoting music, anime, manga or anything similar, the government will pay for half of your travel and accommodation expenses, as well as local transit costs. Surprisingly, only few people know about this. People in bands usually don’t have that information at their disposal. Since I work as a notary I was aware of this, but some aren’t.

I: At one point, we even distributed Tirol Chocolate (a brand of Japanese chocolate) at our gigs. The idea was to promote Japanese candy overseas.

T: We handed out special versions of Tirol Choco – the labels were decorated with our album art.

That’s what you need to do to get a subsidy, huh? Still, it would be great if more indie bands could make use of that system.

T: Our work abroad isn’t something that’s just done in a day. You can’t just go there and decide it didn’t work out and call it quits. We had a terrible turnout our first time overseas, in fact.

I: Even the second time was a fluke, and we just wanted to go home.

T: But the connections you build locally turn into something bigger, and as you build that, something else happens.

I: We’re really happy we decided to take the plunge and go for it while still young. If we hadn’t gone back then, we probably never would have, and would just have regrets instead. So even if it meant holding down part-time jobs to save up and make it over there, it was all worth it! [laughs]

T: Also, when you play overseas and then come back home, you get some ideas about what type of track will get a good response next time you go. You start building tracks while thinking about your overseas fans. That’s huge.

I: It’s almost the primary basis of our work now. The songs on Cubic are sort of built with this idea in mind – the idea of tracks that can be played even in rougher contexts overseas.

Photos by Keisuke Tanigawa