[category]

[title]

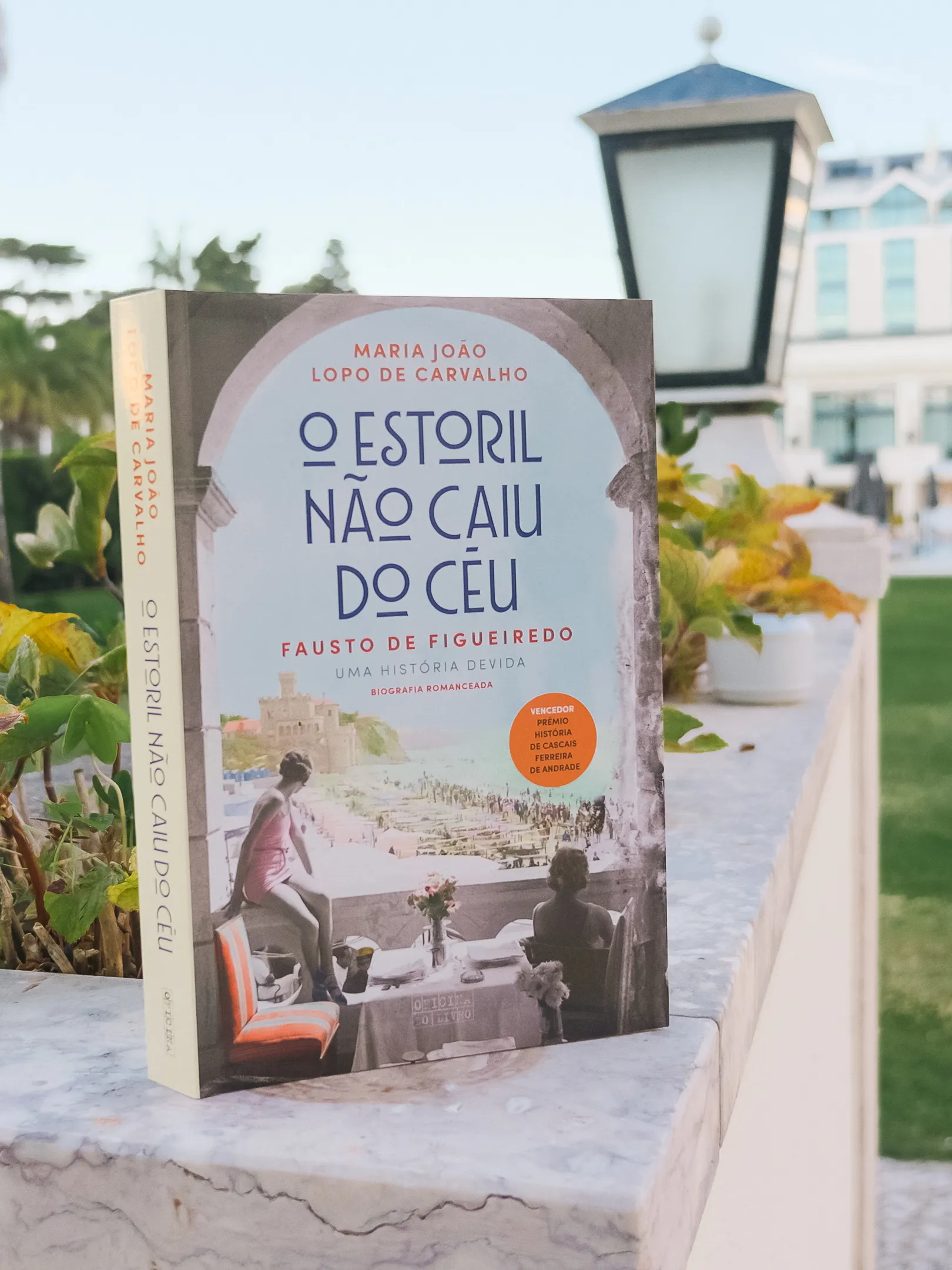

"O Estoril Não Caiu do Céu" is a novelised biography of Fausto de Figueiredo. We spoke to the author about this remarkable story.

The origins of Portuguese tourism and a development project like few others, with spies and war refugees thrown into the mix. That’s the story of Estoril, a meticulously planned area designed to become one of Europe’s most prestigious and stylish spots – a goal it certainly achieved. Maria João Lopo de Carvalho brings this tale to life in O Estoril Não Caiu do Céu, a novelised biography of the man who shaped the Costa do Sol as we know it, entrepreneur Fausto de Figueiredo.

Published by Oficina do Livro, it was officially launched on 17 September and has already won the Cascais History Prize Ferreira de Andrade. Time Out delved into the memories of Estoril and its creator in this interview with the author, who also has local roots.

Why, at this stage of your career, did you want to tell Fausto de Figueiredo’s story through a novelised biography?

Good memories come from the homes where we lived and were happy, don’t they? With certain smells, objects, views, and where particular events happened. One of the places I was happiest was in São João do Estoril, at my paternal grandparents’ house, where I spent every summer, especially during my teens. It was where I could push boundaries – within reason, of course – riding motorcycles, going out to bars at night… That house perched on the rocks, the sea crashing below, the sound of the waves on the balcony… It was a truly privileged setting, but I found myself thinking: who made all this? The casino, the Tamariz… who created it all? And then I realised it was Fausto de Figueiredo, a name that, as a kid, meant nothing to me.

Of course, this all happened several generations ago.

Yes, but when I started writing about my great-grandfather Manoel Caroça – the man who sparked my grandmother’s love for Estoril – I began to connect the dots. They shared the same birthday, 17 September, the day this book was launched, and both were from Beira Alta. They must have crossed paths, and I started exploring these roots. The more I delved into Fausto de Figueiredo’s story, the more I discovered he had married Clotilde, who has an avenue named after her in Estoril, as does her sister Aida. Few people know this. Clotilde suffered from lung problems and had spent a long time in Guarda, at the sanatorium run by my other great-grandfather, Lopo de Carvalho – one of those chalets for the wealthiest families. It was all like a puzzle. Seventeen is my lucky number, I live at number 17, and it seemed written that I had to write about Fausto de Figueiredo. I had also previously written a commissioned story for the Mello family about Alfredo da Silva’s descendants, and everything seemed to converge in Estoril. That’s how I started my research.

I imagine it was a lengthy process.

Yes, people often don’t realise, but a book like this – from which 200 pages were cut at the last minute – takes at least three to four years if you want to do it properly. My aim was to root it deeply. I don’t like misleading my readers. I try to be as rigorous as possible, consulting every source. Of course, there are small mistakes – some details always slip through. But from that rigour, that common denominator, I could give the story wings and make it engaging. And what makes a story engaging? Humanising Fausto de Figueiredo.

With elements that aren’t tangible and data that doesn’t exist?

There are three dimensions. There’s the public dimension – and with Fausto de Figueiredo it was very public indeed: he had been vice-president of what is now the Cascais City Council, which at the time was the Administrative Commission, a national deputy, and had numerous articles published in newspapers… all of that has been wiped away. Then there’s the private dimension, which you can only access through personal letters – of which there are very few – family testimonies, and accounts from people who still pass on the stories they heard, because Fausto de Figueiredo died in 1950; there’s no one left who really knew him, at least not well. After creating this humanisation through private testimonies, there’s the secret facet. And that’s the hardest, maybe even impossible, to reach. So yes, there is a degree of interpretation, both for the public and private sides, in an effort to get to the heart and mind of the man, which was the hardest part for me. So, this is one version.

The book has the subtitle “Uma história devida””, all together. Was it a story that deserved and needed to be told?

I think it’s more than due. People passing through Estoril have no idea what it took to create it and make it what it is today. From the First Republic to the Estado Novo, Estoril and Fausto de Figueiredo’s work were used as Portugal’s calling card. During World War II, thousands of refugees passed through here – Jews, people travelling to America, kings without crowns or courts… I hadn’t realised, for example, that Saint-Exupéry – the author of The Little Prince, our reference – spent several days at the Hotel Palácio writing, not The Little Prince, but other equally important texts. And the Dukes of Windsor, Ian Fleming who created James Bond… Some things are better known than others, but I hadn’t grasped the scale of it, or this overarching structural vision for Estoril, which included the thermal baths, the casino, the Tamariz, the beach, the tram, and the Sud Express from Paris to Estoril. The number of houses, chalets, top architects, luxury hotels, golf courses – which at the time wasn’t even a sport imaginable for the Portuguese – tennis, regattas, horse races, plus many acts of charity and philanthropy. There’s a huge legacy. Beaches, swimsuit parades, foreign women with long legs, high heels, smoking during the Estado Novo… unthinkable. And it was all his idea: when he went to Biarritz he thought, ‘Estoril has higher temperatures, warmer sea, more sunny days. This has everything to succeed.’ How does someone imagine all this, have such a strategic vision, and then work behind the scenes…

To make it happen?

Yes, and make the authorities allow it, right? And believe in the project. Fausto de Figueiredo knew that without a casino and gambling, Estoril couldn’t survive. It was a clever formula, so the games had to work there. He worked hard to make it happen. We all enjoy Estoril, but we don’t imagine what’s behind it. We don’t imagine the genius behind it, though we can say he had a difficult character. If he were here, he’d probably have scolded me: how dare I enter his life? But I discovered another side of him, very human and tender, especially with his three daughters. They melted his heart more than his two older sons. He was, as we’d say today, a control freak. He controlled everything down to the smallest detail. The staff at Hotel Palácio would wait for a signal from his chauffeur – three honks – before going on alert because the boss was arriving. Once, he boarded the train and didn’t have time to buy a ticket, even though he always insisted on buying one. The ticket inspector didn’t recognise him, and he just said, ‘I don’t have it, I didn’t have time to buy it.’ He didn’t reveal himself. When they arrived at Cais do Sodré station, the inspector dragged him to the police to report him. When he realised it was the boss Fausto, he went white. But Fausto de Figueiredo said, ‘No, sir, not only will I pay my ticket, I’ll pay the fine and reward you for doing your duty.’ That was the kind of man he was. He wouldn’t tolerate a delay, but he had this heart.

What surprised you most in your research?

I found it amusing, regarding him being a control freak, the ways he got rid of things he couldn’t control. For example, the first architect of Parque do Estoril was Henri Martinet, a Frenchman and something of a prima donna, already with an enviable résumé. Two very strong personalities facing off. Naturally, shortly afterwards, Fausto de Figueiredo fired him and hired someone else. When he felt he couldn’t control something, he quickly freed himself from it. Another example: gambling was a variable he couldn’t control – you can’t control luck or chance. So he set up a tenant company, which he could control, rather than trying to manage the games directly. And then there were the spies – imagine what spies at the Hotel Palácio, the main Allied hub, would have meant to someone like him. Next door, the Hotel do Parque was the Axis hub. Many years after WWII, during renovations at the Hotel do Parque, they found secret communication pegs hidden in the wardrobes. Imagine what that would have meant to Fausto de Figueiredo.

What astonished me most, beyond his obsessions, were these vulnerabilities. Strengths are often the most visible, but it’s these fragilities that make him so human, and for me, that was the most moving. Of all the variables beyond his control, his obsession at the end of his life was that he would go bankrupt: “I’m going to fail, I’m going to fail, I’m going to fail.” Even though people told him otherwise – he had the railways, the concessions until 1970, the casino running well, royalties visiting… But despite all that, in life’s final moments, he became even more obsessive. Yet he wasn’t just the iron-chested figure immortalised in Parque do Estoril. He was a human being, with all his flaws, defects and qualities. That was the most surprising thing, because everyone talked about his bad temper, his irascibility, his need to control.

Does Fausto de Figueiredo still have living daughters?

No, only granddaughters and great-grandchildren. I interviewed as many as I could, and spent many hours with people connected to Estoril and the companies. I had to approach it from multiple angles. When the Noite Sangrenta occurred in the early 1920s, with several people persecuted and one killed, they wanted to kill Fausto de Figueiredo and Alfredo da Silva – they wanted to wipe out the capitalists. He had to escape through a window and flee to northern France while trying to keep things under control back home. It’s an adventure story. And then you might think things calmed down, but no – the Spanish Civil War came, then WWII, and it all revolved around Estoril. It really seemed like Portugal’s capital. There was even a saying at the time: “Cascais nobility, Monte Estoril grandeur, Estoril grandela,” referring to the wealth of the new rich.

What were the most challenging and difficult sources you encountered?

There were the three dimensions: public, private, and secret. Public sources are, of course, public – I went through all the newspapers, with enormous help from researcher Francisco Fialho at Universidade Autónoma, who saved me so much time. Then everything had to be cross-checked. For example, the Noite Sangrenta: what the family recounts versus what actually happened. The closest record of reality is in the newspapers of the time. Torre do Tombo, the Presidency archives, hold a lot. All his interventions in Parliament, all letters and documents carefully preserved in the Cascais Municipal Historical Archive… it’s endless.

It sounds overwhelming.

The challenge is cutting it down – choosing what’s fundamental for the story. You have to create a compelling narrative, because this isn’t a history book, it’s a book of stories. Based on rigorous research, it shouldn’t be exhaustive. I’m not writing a biography, I’m letting the story soar. That’s why the book ends with dozens of pages of footnotes. My publisher warned me this information is totally boring for the average reader, but I couldn’t leave it out – there are always those who want to know more. Thankfully, we’re in the 21st century, and so much is online. The tricky part is that, in the early 20th century, when people got older, they would burn their personal letters – which is exactly what Fausto de Figueiredo did. There are only two or three letters left with the family. My great-grandfather did the same; it was normal. They didn’t want someone like me digging into what was secret.

But Estoril is my favourite place and always will be. I wanted this book to reach beyond the Costa do Sol, to all of Portugal. If Rui Veloso is the father of rock, Fausto de Figueiredo is the father of tourism. My daughter studied hospitality, and the first hospitality course in Portugal was held in the cellars of Hotel Palácio when Fausto de Figueiredo realised there was no training for luxury hotels. No one knew; staff didn’t speak languages, didn’t understand luxury or customer expectations. He brought in teachers from France and England and created the school himself – another innovation. He also founded Estoril Praia so company employees could practice sports, and even donated land for them to build their homes.

Would you say this book, beyond Fausto de Figueiredo, is also a biography of Estoril?

Yes, absolutely, especially given the wealth of sources available. There’s that fantastic photography exhibition at Casa Sommer, A Invenção do Estoril, which tells the story in images. And it’s amusing that it was Fernando Pessoa who invented the name, isn’t it? Something that no one, not even I…

Invented which name?

Costa do Sol, Terra Prometida. It was in 1928, in Páginas de Pensamento Político, as notes for a propaganda campaign for the Costa do Sol. He coined the name… Later it had to be changed because, in southern Spain, after Fausto de Figueiredo had died, there was already another area called Costa do Sol, so it became Costa do Estoril. Before that, people also referred to it as the Portuguese Riviera or Enseada Azul.

You mentioned the photography exhibition at Casa Sommer, and you also wanted to include some images in the book.

Yes, there’s a section in the middle, with lots of help from the Historical Archive. People need to visualise it too. It’s just a small section, with very few images, but it gives an idea and includes items from the family archive. That way you can see this man, born in Beira Alta, one of twelve children, son of a primary school teacher, who comes to Lisbon because his sister decided it – the parents were elderly, and she was in charge – sleeps in the pharmacy lobby where he lands his first job, and ends up creating this formula. He could only have been a genius, right?

Discover Time Out original video