[category]

[title]

In his first interview since swapping the United States for Portugal, Robert Angel recalls the astonishing way he went from waiting tables to creating one of the most famous games of all time – practically overnight.

At 67, American-Canadian Robert Angel is one of many foreigners enjoying retirement in Cascais. Having lived in the town for a couple of years, the main difference is that, while he blends in on the street like anyone else, Angel created one of the most famous board games ever – Pictionary – where players try to guess words based on drawings, all under a time limit.

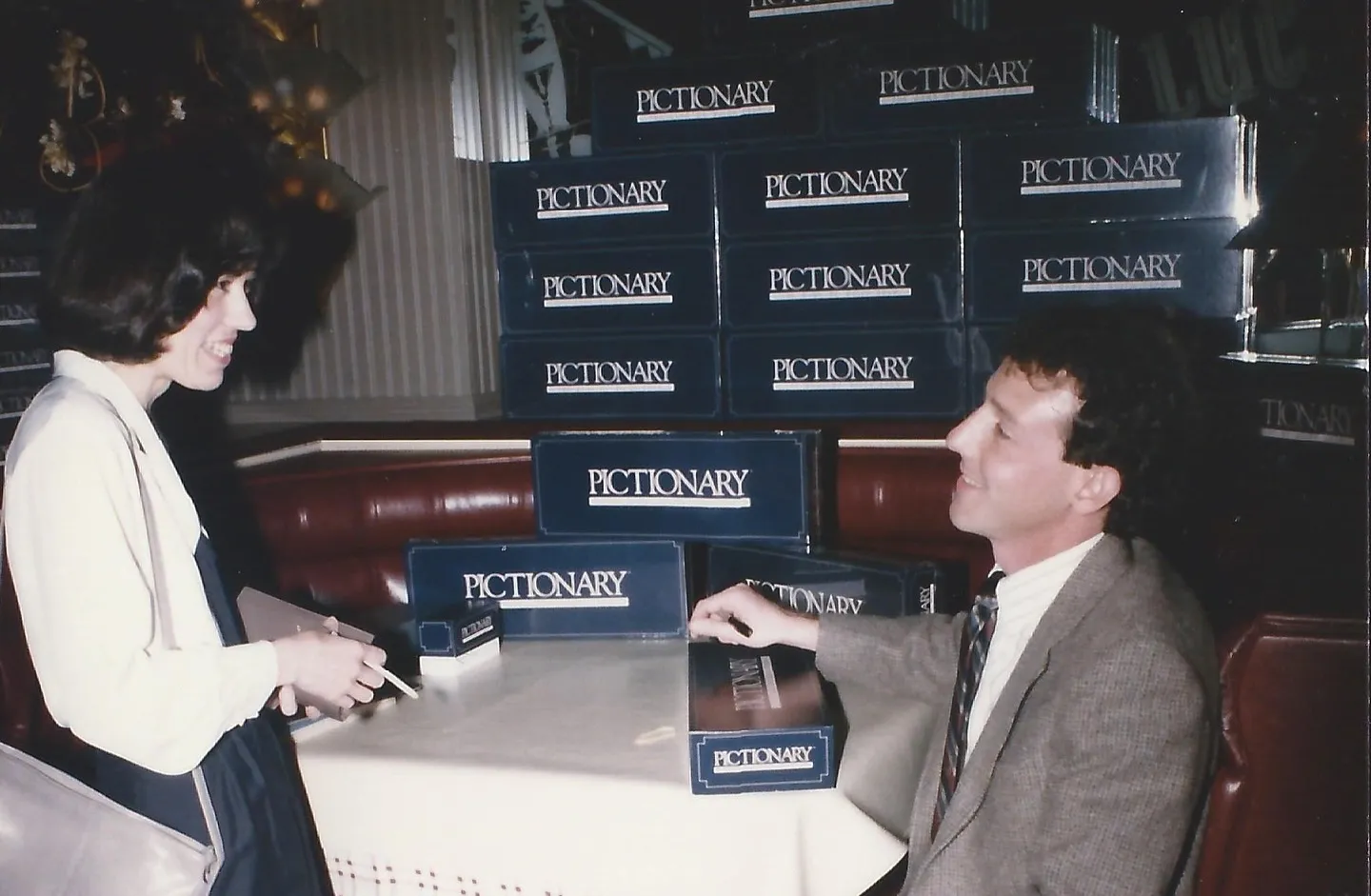

It all started in the early 1980s, when Robert Angel was a fresh college graduate working as a waiter. A casual game he played with his housemates after work quickly turned into his career and a multi-million dollar business. Already an international phenomenon for years, in 2001 Pictionary was bought by Mattel, the world’s second-largest toy and game company.

In his first interview since moving to Portugal, Robert Angel opens up to Time Out about what drew him to Cascais, recalls the wild story behind Pictionary’s invention, and shares touching stories from players around the world.

Why did you decide to move to Portugal?

I’d visited a few times and have a close friend who’s lived here for many years. It just felt natural – I felt at home. I came to visit him once and thought, “This is it.” I’d lived my whole life in the US but always wanted to live in Europe. Portugal and Cascais felt right: great people, fantastic weather, a slower pace. And if I want a bit more energy, I go to Lisbon – which is really close. I love walking around here.

What do you enjoy most in Cascais?

I go on lots of walks. I enjoy the town, even as an American. I have a group of expat friends and on Wednesdays we try to find the cheapest, smallest, most hidden spots for lunch. You know, somewhere we can have wine for under 15 euros. It’s a lot of fun and a great way to discover the lesser-known places. But I also visit others. I’m a big fan of Bougain, the first restaurant I found here. Now, my go-to is Corleone, with that view and location. Being on Corleone’s deck is one of my favourite things.

Let’s dive into the story that made you famous: inventing the now world-renowned Pictionary. I know it started as a casual thing with friends while you were working as a waiter, but how did you begin to develop it seriously? Were you already a fan of board games?

Not really. I’d just finished college at 22, no job, no money, no future. I studied business management, pretty general stuff – always wanted to be in business but didn’t know what exactly. After college, I moved in with three friends in Spokane, where I grew up. We all worked in restaurants. So, we’d get home at midnight, have a few beers and started playing this silly game – literally drawing pictures from the dictionary. It was just something to do, not really a game. Two guys here, two there. You’d take a sip if you won. Easy. But we played every night. Every single night. Then people started coming over. This was 1982, everyone played board games – video games weren’t a thing yet. But I knew there was something in this silly game. I said, “I’m going to do something with this.” My friends thought I was joking. But I insisted, “No, seriously, I’m going to make something of this.”

So you recognised the potential?

Yes – I come from an entrepreneurial background. I’m naturally an entrepreneur and I liked being involved in that world. But it was totally unexpected. I didn’t have a grand plan. Nowadays, if you start a business, you have to show projections, have a plan. I just said, “I’m going to make a game and see what happens.” Kind of like what Mark Cuban or Sara Blakely did.

But like I said, you weren’t really a big board game enthusiast. Were you good at drawing?

Well, I can tell you this – you don’t want Mr Pictionary on your team! [laughs] I’m terrible. It’s kind of become my trademark, my badge of honour. I’ve actually avoided learning to draw. I’m only good at guessing. And in my defence, that’s the fun part of the game.

The guessing part?

No, no – when you can’t draw. The frustration is the fun!

Do you still play nowadays?

Not much. When I do, I still enjoy it. Sometimes I play with my kids – and they usually beat me. Actually, let me correct that: they always beat me. They’re 29 and 31 now. I love spending time with them, and every now and then we’ll play Pictionary. It’s still fun. And people still want me to play with them...

So it’s a pretty big part of your life.

Yeah – and it’s also changed a lot of people’s lives, which I never expected. When I created the game, it was just a party thing. We thought we might make some money, that was it. I had a silent partner – a financier. And two partners who ran the business with me, each with different skills. I did sales and marketing and actually created the game itself... I made the word lists. One partner worked with me in the restaurant and was a graphic artist. The other was a friend of a friend… I tested the game a lot, spent hours taking notes. Every few days I’d have a new group of friends testing the game and tweaking the rules. One of these guys showed up one night and we played on the same team. He had a terrible stutter, so he couldn’t guess in time. We had so much fun. And he just said, “I’m in. If I have this much fun and I’m this bad, I’m in.” It was perfect.

So Robert went from full-time waiter to full-time Pictionary manager with his partners?

Yes, but it took some time. We spent about 18 months putting everything together while still working our day jobs. We officially launched the game in June 1985, and by October I think I’d quit my job. But I wasn’t making much money yet – maybe $500 a month – we were hustling. But honestly, that was the most fun part of the whole story. We had no clue what we were doing back then – just experimenting and having a blast.

And even when it started to take off, I guess you never imagined it would become a global phenomenon, spanning generations, and that we’d be here in Cascais talking about it all these years later?

No, not at all. At first, my expectations were very low. We didn’t think we’d change the world or make big money. It built up gradually. Looking back, I had no idea we’d sell tens of millions worldwide. And the best part is the stories people tell me. That was never expected either.

Care to share one?

I have lots. Once, I met a woman – an artist in California – and we became friends. She told me that as a teenager in Latvia, to save energy, the power in her building was cut every night between 7 and 9 pm. So everyone would gather in the common room at the end of the hall, by candlelight, to play Pictionary, which had come from the US in the early 90s. That’s how she learned English and started drawing on the walls because they didn’t have paper. They were drawing Pictionary on the walls! And that’s what sparked her passion for art. Now she’s a successful artist in California.

What a great story.

I have stories of all kinds. A few years ago, I was having dinner in a restaurant, and the waitress found out I created Pictionary. She immediately started crying. I asked her what was wrong. She told me she was an orphan. She’d been moving from foster home to foster home, and all she wanted was a family. She wanted to belong somewhere. One day, she was taken in by a family – a mom, a dad, and three kids. But the kids didn’t want anything to do with her, and she was sad. One night, the parents took the Pictionary game out of the cupboard, and they all started playing – parents and her against the three siblings. And apparently, she was really good at Pictionary, and her team won. Since she was having fun, happy, and opening up, instead of staying shut off in her corner, suddenly the siblings started seeing her as a person in their home, not just someone who was there. They kept playing, and the kids wanted to be on her team. That’s how they really became a family. Because of Pictionary, this woman found the family she was looking for. It’s one of my favorite stories – it’s amazing how a game can change lives.

In those first months working on the game, naturally, there were no guarantees it would work out, let alone like this. How did your parents react? Did they believe in the idea right away?

You know, back then there were no cell phones, no constant communication like now. But my dad was like, “Go for it, good luck,” not a helicopter parent. My mom supported me too. They were just happy I was doing something. They didn’t pressure me to make it work, nor did they hold back my ideas and goals. It was a good environment. Then they were surprised, like all of us. Not knowing was part of the fun. We had no clue what was coming next, where we’d sell, who would play. There were those sales calls: “Will they accept it or not?” And with each sale, with each story, our confidence grew.

In the early months, you sold the game yourself, right?

I sold it out of my car. Literally, no joke. I didn’t know how this stuff worked, didn’t know the rules. Supposedly, you’d sell to toy stores or big chains like Toys “R” Us. But we didn’t have access to those companies, and back then they wouldn’t accept independent games. So I thought, “Hey, a car dealership should have a Pictionary game on the counter for people buying a car. Oh, a hair salon should have Pictionary so customers can play while getting their hair cut.” I went to all kinds of stores.

Did it work?

Yes. Back then no one sold games, now games are everywhere. I sold in pharmacies, even a real estate office. Who does that? I walked into a Century 21 office, just coming from my room: “Hi, I’m Rob Angel, I created this game. What if you had one at the counter while showing a house? Maybe it would say something to people.” They bought six. That was one of my first sales.

You’re describing a very local dynamic. How did it grow to become national, and then global?

It was word of mouth. People in Seattle played and took it on family vacations. Then sent it to relatives. Suddenly, we started getting calls from all over the country. We’d send six here, six there. We got lucky on the West Coast – Nordstrom loved us and stocked our games along the coast, we hit California and it was huge. It caught on fast. We went from me selling in stores to, a year later, selling nationally. Two years later, worldwide. It was crazy and unprecedented.

You later created another game, ThinkBlot. Do you still think about new game ideas?

I’m really retired now. ThinkBlot was a lot of fun, once again the creative process was great. But when I sold the company, I realized I love games but not the games business. When people sell their companies, everyone says, “You have to do it again, prove it wasn’t a fluke, make another game…” Not for me. I said I’d take some time to figure out what I wanted to do. That included, as you’ve seen, staying home. Not just staying home, but enjoying time with family, raising my kids. I did some mentoring, traveled a lot, worked with nonprofits. That’s what gave me joy, not another business. When it happened, everyone said, “Ah, you can’t be that happy, your life can’t be just that.” Now that we’re all a little older, everyone says, “I wish I’d done the same, you were right.”

And as a consumer, do you keep an eye on the board game market? Do you like trying out new games?

I’m just a regular person. I could be really focused on that industry, but I’m not that much. But my brain never really switches off creatively. In my head, I almost turn everything into games – it’s something I just can’t stop doing.

Do you remember any word you included in Pictionary that turned out to be really hard to guess?

In the very first word list, I thought the hardest word was “area.” Nobody would get it, no one could guess it. But people did. I thought it was almost impossible, but they got there. So I don’t know if there are many words that are really, really hard. The important thing, the only rule, is that it has to be a word everyone knows.

How would you draw the word “Cascais” if it came up in Pictionary?

That’s why I’m bad at the game. What I’d do is draw the streets, the cafés, the bay... No, nobody would get it, it could be any town or city. Now that I know how to play better, I’d draw a map of Portugal and put a dot on it. It’s called context – something I’m not very good at. I’m too literal for a creative guy.

Discover Time Out original video