At the [node:33023 link=Harris Theater;] on November 18 and 19, [node:15021487 link=“The Legacy Tour”;] brings the Merce Cunningham Dance Company to Chicago for the last time. Its founder, choreographer Merce Cunningham, died in 2009; the company has been traveling the world ever since, but will disband after a series of Events—collages of excerpts from longer pieces—December 29–31 at NYC’s Park Avenue Armory.

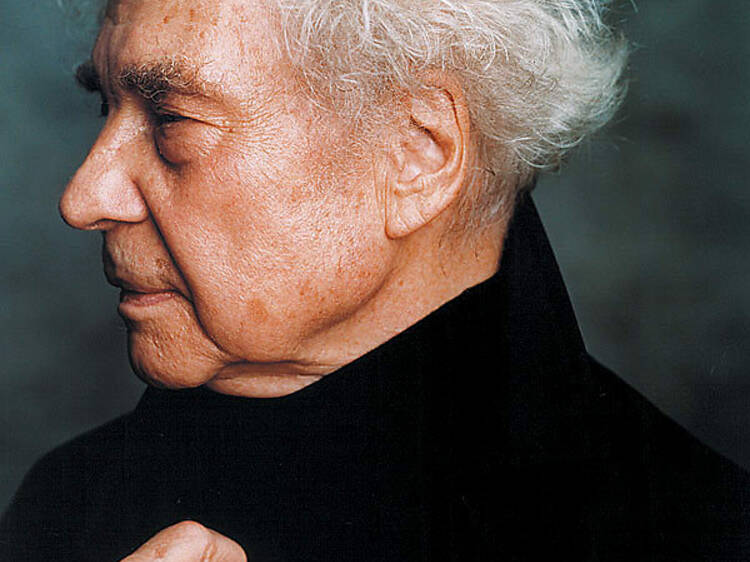

Here, published in full for the first time, is our interview for TOC Issue 137, given by phone on September 24, 2007. Cunningham was 88.

There’s a story that some early funding for your company came from John Cage’s obscure knowledge of mushrooms. Is that right?

Oh, yes, he was on one of those contest shows in Milan, and every week they would ask him questions about mushrooms. It came to the last question, a complicated thing about identifying wild mushrooms. He was an amateur, but a very good one. [Laughs] And he had the correct name. And the Italian audience in the studio were in an uproar.

You both kept a lot of plants around the house. Do you still?

Oh, not so many anymore. I have one that looks like a corn plant, only it’s at least ten feet tall, maybe twelve! Like a tree.

I love the plants in your book of drawings, Other Animals. Do you draw every day?

Yes. At the moment, I’m drawing little birds.

But you haven’t shown your drawings in public much, until recently.

Well, I never would have exhibited them, but Margarete [Roeder, a New York gallerist] offered to show them.

You say that as if she coerced you.

Yes, I would say that that’s what it was. [Laughs] I would never have bothered, but she said, “No, no, I would like to show them.” So she did.

You premiered two solo dances here in 1943 with Cage. Was that your first time in Chicago?

No, I came to Chicago when I was about 12, with my mother and brothers. There was a World’s Fair. I remember the area around the lake had all kinds of exhibitions.

Do you remember where that first concert here was held?

It was with… [Pauses] Jean Erdman. That’s right. It was in the [node:31363 link=Arts Club;] [of Chicago]. There was a small auditorium. It was wonderful that it was even arranged. And I was very grateful to, I think her name was Rue Shaw, who was the head of the Arts Club then. She helped arrange it. I don’t think it was a very long program.

Just two solos, according to what I was able to find: In the Name of the Holocaust and Shimmera.

Yes, those were early solos.

Early on, you also danced with [node:14891619 link=Martha Graham;]. Recently, you collaborated with Radiohead and Sigur Rós, and with painters like Terry Winters. What’s it like to have witnessed these huge shifts?

I think the shifts began in the ’50s. They weren’t noticed by many people, but that’s when the composers began to use electronic sound as a compositional medium. The painters—like the Abstract Expressionists and later Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg—were beginning to appear and, uh, my own work, which of course was not noticed very much here. But I went on doing it because I kept thinking it was interesting and maybe after a while somebody else might find it interesting.

I think it’s safe to say that we have.

Well, I don’t know. I think I just go on anyway. [Laughs] If you’re interested in what you’re doing, then that’s what you do. The fact, in my case, that more people are interested in it [now], of course, is useful because then we can perform more. But it wasn’t so much here as it was in France that we gradually had a large reception.

What do you think it is about the French that makes them so responsive to your company?

I don’t know, but I’m certainly grateful. [Laughs] In any event, it’s been remarkable. But we have friends in the United States, too.

You certainly have friends in Chicago.

Yes! Oh, that’s it: I wanted to say how much I like the [Harris] theater. I like the fact that you go down [underground, to enter]. It’s very interesting! And you’re so amazed at the size of it, when you consider that you’ve gone in the elevator, what, three or four floors down.

Which also takes care of the cell-phones-ringing-during-the-performance problem.

[Laughs] Yes, that’s true.

You opened your creative process wide to chance, incorporating the I Ching and other methods. How does expressing yourself personally fit into that?

I think it begins, of course, personally, but when you use chance, it opens up so many things that you hadn’t ever thought of and it’s like, “Open, sesame!” And even if something comes up that is not quite possible, it shows you something else that you hadn’t thought of that is possible. It’s like being open to the world.

You’ve never rolled the dice and, when you followed where they led, it was a terrible idea?

No. [Laughs] No, I always try to see, What is it that’s come up this way, and how can we use it? And even if we can’t do what it indicates, it’s indicated a number of other things, which I found, add to my experience.

They lead your thoughts in a new direction.

Yes, yes.

What about programming concerts? Is that another roll of the dice? Do you take what’s active in the company’s repertoire and put a concert together by chance, or do you try to set up a dialogue between certain pieces?

Usually, that has a great deal to do with practicality. [Laughs] We try to keep as many pieces available, given our circumstances, as we can. We don’t really [program] by chance, because I do like to let all of the dancers dance, and it might come up [if scheduling by chance] that we’re using the same [dancers] all of the time. [Laughs]

The Events that you’re doing now, and the MinEvents, are a way to do that even more, right?

Yes. Right.

It says on your company’s website that you’ve used your computer software for random choreography, DanceForms, in all of your work since 1991. It must occasionally generate steps that are physically impossible.

Yes, you try it out and think, “Oh, I can’t do that. But this—I’ve never done this before!” It’s an opener. It can open your spirit.

Has it been an obstacle in any way?

No. If it’s kept me from anything, it’s [because of] the way I’ve used it. Oh, and it all goes back to my principle in giving movement: If you do it on the right, learn it on the left. And if you do it on the left side, it will reinforce the right.

And forward and backward.

That’s right.

Ten years ago, you said in an interview, “I don’t think we have that much access to technology that it could get in the way.” Do you still feel that way, or is our relationship with technology becoming more complicated than that?

Because technology keeps changing and adding things to what can be done, unless you can keep up with that, you don’t know what [technology] is, even. So in that sense, although I like to, it’s very difficult. Also, in our way of working, [we have] to find a way to work with it, find access to it, although we’ve had some luck on that. And, for instance, this thing with the iPods: It’s something we could do, that we could use within our way of working, that is also part of the recent changes, certainly, in sound.

Right, eyeSpace, which you’re bringing here: The audience members listen to Mikel Rouse’s score on iPods, through headphones, and not everyone hears the same sections, or hears them in the same sequence.

And also there’s this environmental sound that’s going on at the same time. Any spectator has the choice to listen to whatever.

Although Rouse has said that he doesn’t want audiences listening to Megadeth on their iPods instead of his own score. Is Megadeth okay with you?

It’s okay with me, really. Our principle has been that sound is separate from sight, that they coexist. And when you’re wearing an iPod, you’re seeing something and hearing something, and they have no relationship other than the fact that they’re taking place at that moment. That is very much the way we have worked.

It’s what you’ve explored your entire career, and now it’s a cultural norm.

[Laughs] Yes! I think it’s poetic. I like that idea.

There’s a trend where people go to parties wearing iPods, so they dance together but—

But they’re all dancing to different music?

Yes.

I didn’t know that. It sounds superb.

It sounds like one of your concerts.

It leaves everybody making up their own mind.

And yet you’ve found some very rich partnerships with like minds. It must be great to have collaborated with Rauschenberg, for instance, for so long throughout your career.

Yes, and he’s designing the decor for a new work we’re making. He has a brilliant imagination for theater, aside from his imagination for painting. Somehow, whatever his theater sense tells him, he’ll make it some way so we can use it. Because we have to be practical, to be able to carry things on tour.

Well, that’s something that hasn’t changed. You used to tie his decor and costumes to the roof of the Volkswagen bus.

That’s right! When we traveled in the bus, that wasn’t easy, but you certainly got to see the country. There was an awful lot of laughing.

And driving and playing Scrabble at the same time.

That was John Cage. He drove most of the time and, yes, he would play Scrabble, with anybody that would play with him. He seemed to like driving these hours. It got us to play in places that otherwise we would never have played in, I’m sure.

You were able to get up and go at a moment’s notice.

More or less, yes. I remember once leaving New York in an incredible blizzard and driving to Chicago. We took the Jersey Turnpike and then the Pennsylvania Turnpike and on and on, through this heavy, heavy snow.

I’ve made that drive myself in bad weather. It can get a little hairy.

Oh yes and, boy, there were lots of cars spilled off on the sides. We didn’t go very fast.

We’re glad you made it. Now, these fellow experimentalists, in all of these different genres: Through the years, you’ve all been “walking through the forest together,” if you will.

Yes.

And Robert Rauschenberg is one of those people—

Indeed, he is.

—who’s asking many of the same questions you are, just with different tools.

Yes.

How big a role does being part of the same generation play in collaboration? What’s it like working with younger artists?

Well, eyeSpace has decor by [Henry] Samelson, a young artist here in New York, who made a drop for us.

Based on a painting that isn’t very big, right?

Yes, yes.

How did he feel about having it blown up to the size of a theater backdrop? Did he like it?

Yes. He’d never done anything in the theater before. If you see someone whose imagination strikes you some way, I always like the idea of asking if they would be interested in putting it in the theater. I think on the whole we’ve been fortunate with the designing that’s been made for us.

Certainly. Seeing your company is as much a visual art experience as it is a dance experience. I know you’ve worked with sculpture before, such as in Walkaround Time and Way Station. Do you think you’ll work with onstage sculpture again?

Not at the moment. Well, actually, there was a young artist in Miami, Daniel Arsham, who made…I don’t know how to describe it. It’s like an object which was placed on the stage, and it was two separate things, and it occupied the space in a way that didn’t really get in our way. It was interesting to have. Again, he’s young, I don’t know, 25 years old. I like the idea of having young people, who have some kind of invention, work in the theater. The way we work is, well, mainly free rein, not telling them what to do. [Arsham] had an interesting idea about theater, was very much was occupied with the fact that people enter on one side and leave on the other, across the stage. Somehow I’d never thought of it that way. So he made something which had an opening at the top. It went vertically, rather than horizontally. His mind jumped that way about theater. That’s what he saw. It wasn’t something that we could have predicted, neither one of us. Or certainly with the music, what the result would be when you put them all together.

You must enjoy those moments.

Yes.

At 88, you’re collaborating with 25-year-old sculptors. How do you account for your insatiable appetite for new work?

I always think there’s something else. Daniel Arsham uses materials that 20 years ago didn’t exist. I think it must be the same in dancing. There’s always something else.

If you want to be in the arts, you ought to know something about all of them, as Nellie Cornish told you. You’ve really taken that to heart.

That was her principle and I think it’s a superb idea. Because otherwise dancers get so engrossed in their art they don’t know anything about any other art. I went [to Cornish College of the Arts, then the Cornish School] to be an actor, but I liked dancing, so I took it. It proved to have a stronger lure.

Do you still dance?

Not really. But I’d love to be able to get up and do a jig.

Merce Cunningham Dance Company presents its final performances in Chicago at the Harris Theater on November 18 and 19.