Silvio Foretić

The enfant terrible of Croatian music in the Sixties, Foretić was the first to compose music for tape, and headed the Ensemble for Contemporary Music, an experimental performance group much influenced by John Cage.

For essayist and music critic Igor Mandić, May 24 1961 was the day on which the international avant-garde finally arrived in Zagreb. The late-night performance of an electronic work by French composer Pierre Schaeffer was the city’s first encounter with music performed by a piece of technology (in this case an old-school reel-to-reel tape recorder) rather than a live musician.

The concert in question was part of the very first Zagreb Biennale, a festival intended right from the start to serve as a platform for contemporary music. The international art symposium known as New Tendencies first took place in Zagreb in the same year – both events helped transform the Zagreb of the Sixties into a fulcrum of the global avant-garde. Or at least that’s how it was enshrined in local mythology. Like most avant-garde events, the Biennale had an electrifying effect on a small number of enthusiasts and critics, and was largely misunderstood or ignored by everyone else.

Legend has it that Biennale founder Milko Kelemen exploited Cold War rivalries to get the festival off the ground. Having sweet-talked Moscow into sending him the Bolshoi Ballet, he then persuaded the Americans into letting him have the avant-garde musicians he really wanted.

In its Sixties and Seventies heyday, the Biennale attracted composers of the calibre of Igor Stravinsky, Olivier Messiaen, Witold Lutosławski, Krzysztof Penderecki, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luigi Nono, many of whom premiered works specifically commissioned by the festival. The first edition of the Biennale prompted an article in the New York Times entitled 'Revolution in Zagreb', generating the kind of cultural soft power that nowadays only comes from the Adriatic tourist industry or location shoots for Game of Thrones.

Recent interest in the art and architecture of the Cold War period has enhanced our appreciation of Zagreb’s cutting-edge role. The Croatian capital was one of the most culturally active cities in the socialist, non-aligned federal state of Yugoslavia, and arguably benefited from the creative possibilities this between-the-blocs status engendered. Indeed the ambiguities of culture in this period have become a major intellectual preoccupation, with historians riffling through the art, architecture and music of the epoch like DJs searching for rare grooves.

Fitting therefore that one of the keepers of Croatia’s avant-garde musical flame should himself be a former DJ of some distinction. Sound engineer and composer Višeslav Laboš was a cutting-edge knob-twiddler in Zagreb clubs when he began to explore electronic music’s experimental roots. 'I remember reading Wire magazine in the early 2000s' he says, 'and being intrigued to see front covers where the names of contemporary DJs appeared alongside the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage.'

This launched Laboš on an obsessive quest to piece together the history of electronic music in Croatia, from the earliest exercises in experimental music to the commercial synthi-beat bands of the 1980s. Together with cultural historian Željko Luketić, he put together the compilation Electronic Yugoton: Synthetic Music From Yugoslavia 1964-1989, a 2-CD set which placed the electro-pop acts of the Eighties side-by-side with the avant-garde composers of the Sixties and Seventies. The tracks were culled from the archives of Jugoton, the Zagreb-based record label (still operating, but now under the name of Croatia Records) that signed acts from all over the former Yugoslavia. Electronic Yugoton doesn’t therefore just include chart-topping Croatian synthesizer duo Denis i Denis, but also acts like Belgrade pop conceptualists U Škripcu and Ljubljana’s disco-Goth pioneers Borghesia. However it was Laboš’s inclusion of previously-unreleased experimental work from ‘serious’ composers like Igor Kuljerić and Silvio Foretić that took people by surprise – people knew that they were well-respected figures in contemporary music, but had little idea how far-out their electronic works actually were.

Laboš’s next CD project, U potrazi za novim zvukom (In Search of New Sound), dug deeper into the archives, presenting 21 electronic works by 14 composers. Laboriously pieced together from old tapes, it was a pioneering exercise in cultural reconstruction that made the forgotten world of Croatian experimental music look much richer and intriguing than anyone had previously supposed. Laboš went on to release further CDs dedicated to two of the key composers, Silvio Foretić (born 1940), who studied under Stockhausen and has always been associated with the avant-garde, and Igor Kuljerić (1938-2006), who was a conductor and orchestral composer as well as an enthusiastic dabbler in new technology.

Igor Kuljerić served as artistic director of the Biennale in the early Eighties, widening its appeal by introducing an alternative rock strand to the proceedings. Gang of Four famously played here in 1981 and went on to exert a significant influence on the Zagreb post-punk scene. It was Slovene group Laibach’s turn in 1983 – their blend of industrial cacophony and totalitarian imagery touched too many nerves, and the performance was shut down by the police.

The guest who had most impact over the years was American composer John Cage, whose works formed an important part of the first Biennale, and who performed here himself in 1963. Cage returned as composer in residence in 1985, when his piece A Collection of Rocks was performed by over 150 high-school children spread throughout the foyer of the Lisinski Concert hall.

In a sense, however, the Biennale existed as a platform for the international A-list rather than a showcase for home-grown talent. This was particularly true of the electronic side of things, which didn’t feature in the Biennale until 1969. As Silvio Foretić once joked to Višeslav Laboš, the Biennale existed in order to show what was going on in the world but also what Croatian composers themselves were not allowed to do.

In this sense the Biennale was a typically ambiguous expression of Cold-War culture, demonstrating that non-aligned Yugoslavia was cool enough to host the likes of Cage, but stopping short of fully legitimizing the freedom of its own artists. Indeed foreign participation in the Biennale has tended to dominate the way the in which the festival is written about. Far more attention has been paid by historians to what Cage did in Zagreb than to the Zagreb scene itself.

Frequently denied access to the Biennale, local composers were able to perform new works at the Musical Forum (Muzička Tribina), an event held every other autumn in Opatija. It was here that audiences could hear the far-out tape and electronic pieces that are nowadays considered emblematic of the era, but which at the time were rarely heard.

The Biennale itself is still going strong, although it has lost much of the cutting edge that initially made it world famous. The cause of experimental music has been taken up by ZEZ (Zavod za eksperimentalni zvuk or Institute of Experimental Sound), a festival which this year took place in the decidedly non-concert hall environs of the KSET student cub.

The fact that Croatia’s electronic avant-garde never played a major role in the Biennale in the past and is still not on the repertoire today is an inexplicable omission that Višeslav Laboš has spent years trying to correct. The otherworldly music on the Laboš-curated Igor Kuljerić compilation is as haunting and beautiful as anything ever recorded by a Croatian composer.

For Laboš, the uniqueness of Foretić, Kuljerić and others of their generation has much to do with the fact that they had to be quite determined and resourceful to get anything down on tape. 'Croatian composers rarely had the luxury of being allowed to use studios for a long period; Kuljerić was able to record in Milan due to his friendship with the studio engineer, and there was a certain guerilla quality to Croatian works of this period. This is what gives them a certain emotional feel – they were not part of the regular programme of these studios, and had an immediacy and warmth that other electronic works lacked.'

See below our pick of five sonic pioneers from Croatia's electronic music scene.

Electronic Yugoton: Synthetic Music From Yugoslavia 1964-1989 is available from Croatia Records

The enfant terrible of Croatian music in the Sixties, Foretić was the first to compose music for tape, and headed the Ensemble for Contemporary Music, an experimental performance group much influenced by John Cage.

Electronic music was just one aspect of Kuljerić’s career as composer, conductor and all-round organizer; his genre-busting experimental compositions possess a rare beauty.

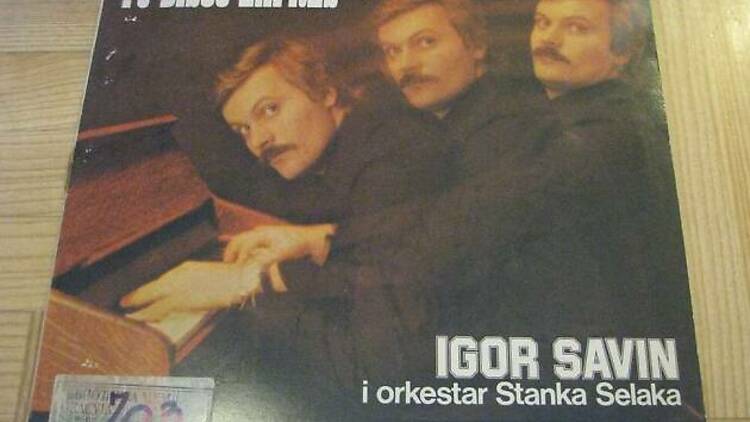

Prime exponent of early moog synthesisers, Moroder-style electro-disco and dreamy instrumentals, Savin’s 1982 album Childhood is Croatia’s answer to Tangerine Dream.

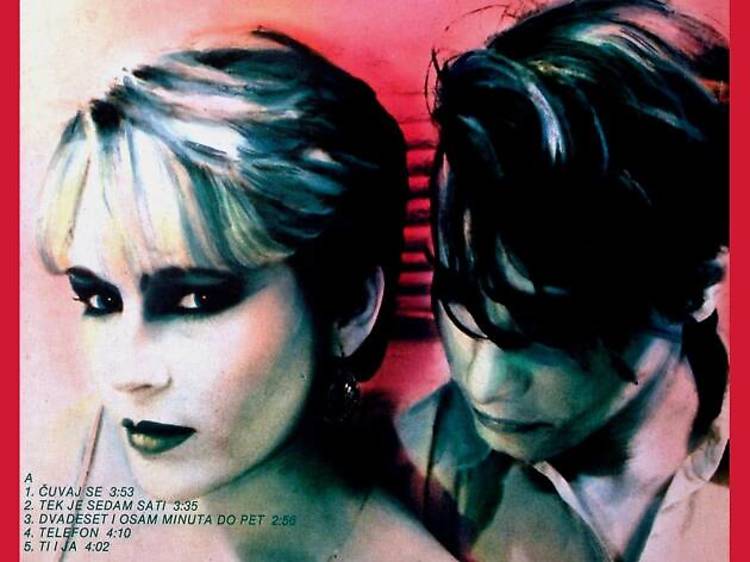

The Rijeka-based duo took the keyboards-and-vocalist template from the UK synthi-pop scene of the early Eighties, and turned it into a pan-Balkan hit machine.

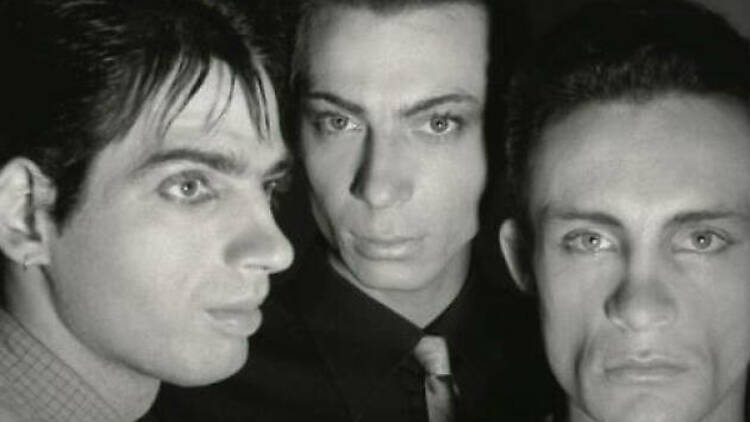

There’s something distinctly Roxy-Bowie-Simple Minds about Dorian Gray, Croatia’s slickest Eighties outfit. Their second album 'Samo za tvoje oči' (For Your Eyes Only) represents the peak of local synthi-rock-pop production.

Discover Time Out original video