Let me confess right from the start, when the opportunity came to interview Saran Yen Panya – Thai craftsman, storyteller and creative director of 56 Studio, known for turning the mundane and the ugly into something fabulously chic – I was a little nervous. In the design world, he’s practically folklore, widely recognised by anyone even remotely in the scene. And me? My design experience is, quite literally, zero. Or perhaps at best, poetic appreciation. So sitting down with someone who spins everyday banality into cultural commentary felt… daunting.

I first encountered his name in Songkhla Old Town, courtesy of a mischievous little bar titled Grandpa Never Drunk Alone (cool, right?). I’d never met the man, yet the design – instinctive, odd, quietly brilliant – struck me like a late‑night revelation. Fast‑forward and I’m on a video call, notebook poised, interviewing him for Time Out about his creative journey, Bangkok’s art ecosystem and how he reads the city’s pulse today.

Saran doesn’t just call himself a storyteller. He also self-identifies as an underdog – a term loaded with defiance, humility and honesty. His worldview, personal history, social observations and even taste all stem from a place of being second-guessed – and rising anyway.

The three eras of Saran

There’s a pleasing symmetry to how Saran narrates his life’s work: three clear-cut eras, each a slightly altered shade of the last. He calls it ‘evolving, not reinventing,’ which feels apt for someone who once built fabulous chairs out of plastic crates.

The first phase was, in his words, ‘chaos and noise.’ He was young, unfiltered and designing for provocation. ‘I wanted to shock people,’ he admits. The series Cheap Ass Elites did just that. Reclaimed, mass-produced materials reimagined into furniture that wouldn’t look out of place in a Bond villain’s lair – if said villain grew up next to a wet market.

Era two softened. He started working with communities, embedding himself in small towns and subcultures. Projects became slower, more intuitive.

“It stopped being about me, and more about what stories I could help tell.”

Now, he’s in what he jokingly calls ‘my retirement.’ He laughs often but doesn’t really mean it. He still creates – only now, it has to be worth it. ‘I say no to almost everything,’ he tells me, ‘but when I say yes, it has to be iconic.’ There’s no room for filler. No energy for pretense.

Bangkok, inspiration, exhaustion

It’s not hard to see where his visual vocabulary comes from. Saran’s Bangkok is both muse and menace – a place of contradiction that constantly gives and takes. He lives in Phra Khanong, a pocket of the city where old Bangkok still whispers. It’s not romanticised – just real. Second-hand shops, cracked pavements, laundry hung without shame.

‘You walk two blocks and it’s like… glass buildings, cafe chains, influencer murals,’ he says, deadpan.

“The beauty and the crap coexist. That’s Bangkok.”

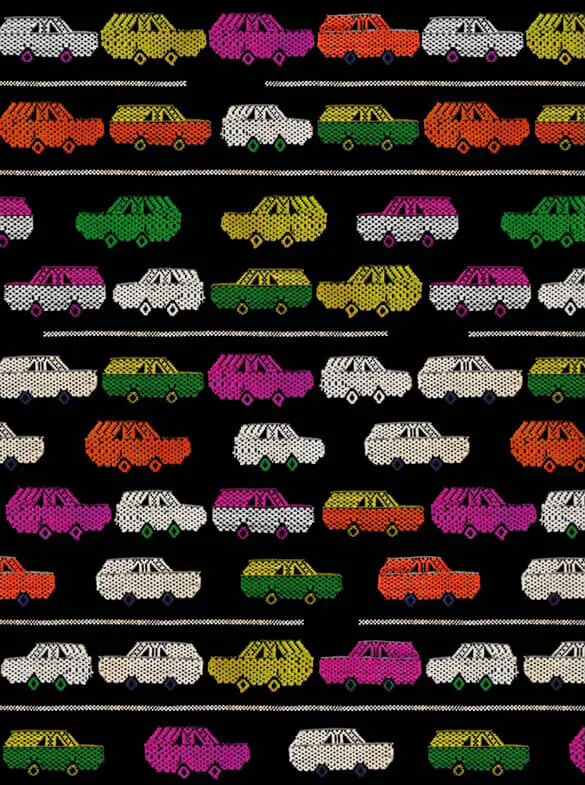

He doesn’t like travelling, so instead, he makes Bangkok work harder. Traffic jams? A textile concept. Pigeon-stained shopfronts? Moodboard gold. ‘There’s soul in places people overlook,’ he says, citing Pak Khlong Talad and Sampeng as creative triggers – though Song Wat, he laments, has become ‘too curated’ and he blames Time Out for it. ‘And malls?’ he pauses. ‘Never.’

Then and now and how the scene’s shifting

When asked how Bangkok’s creative landscape has changed, Saran doesn’t hesitate. ‘There’s more diversity – in every sense,’ he says. Not just in who’s making art, but who’s paying attention. The influx of small investors, brand-collabs and space-makers has created a new kind of power – quieter, but with reach.

Then and now and how the scene’s shifting

When asked how Bangkok’s creative landscape has changed, Saran doesn’t hesitate. ‘There’s more diversity – in every sense,’ he says. Not just in who’s making art, but who’s paying attention. The influx of small investors, brand-collabs and space-makers has created a new kind of power – quieter, but with reach.

‘It’s less about status now,’ he notes. ‘You don’t need to be in some elite circle. There’s an energy of, like… I’ll just make the thing.’ He lights up when talking about the new generation – artists less concerned with legacy, more interested in immediacy. Raw, a little messy, but entirely sincere. Described as a fuck it concept. It’s a kind of creative democracy – one that doesn’t require perfect grammar or polished statements. Just intent.

What he hopes comes next

Despite the fatigue and occasional cynicism – ‘Bangkok will always break your heart,’ he jokes – Saran is still hopeful. Not wide-eyed or utopian, but steady.

‘I want more talent, more Gen Z,’ he says. ‘More wrong choices. More artists who don’t care if it makes sense.’

He believes Bangkok has the potential to be a city where subcultures can thrive without needing to apologise. Where creative work doesn’t have to be aestheticised to be appreciated.

“If we can let go of the idea of what things should be – what’s ‘nice’ or ‘tasteful’ – we’ll get something real.”

There’s a pause before he adds: ‘Ugly’s not the enemy. Safe is.’

But the real change, he insists, is coming from Gen Z. ‘They’re brave,’ he says. ‘They don’t wait for permission. They don’t care if it’s perfect. They care if it feels true.’ He speaks with a kind of awe – not performative praise, but genuine respect. ‘They’re building culture in Google Docs, in group chats, in bedrooms. We should be paying attention.’

And with that, Saran signs off. No dramatic exits, no teachable moments. Just a man who once made chairs out of a basket – and dared to call it beautiful, which they truly are.