The Block Museum’s “Drawing the Future: Chicago Architecture on the International Stage, 1900–1925” examines the exchange of ideas that took place between Chicago and European architects during the early part of the 20th century. Curated by Northwestern University professor David Van Zanten, the exhibition presents more than 50 works on paper, placing emphasis on the grand visions of urban planning.

The show’s layout is not ideal. A theme panel titled "The Canberra Moment" greets visitors entering the main gallery. It outlines the international competition to design the new Australian capital in 1911. To find the real beginning of the show, however, visitors must walk around the corner where designs from Daniel Burnham’s influential 1909 Plan of Chicago are located.

Three of the Plan’s sumptuous original drawings—rendered masterfully by Jules Guerin (1866–1946)—are on display. The showstopper is an oversize perspective drawing (four feet wide by seven feet tall) presenting a birds-eye view of Michigan Avenue. In it, Burnham and Guerin have transformed a once humble street into a grand boulevard that connects the Loop with Streeterville and terminates with the old Water Tower. Although Guerin created this rendering between 1907 and 1908, no automobiles or skyscrapers are depicted; instead, horse-drawn vehicles cross a new Michigan Avenue Bridge and trot past low-rise buildings sporting neoclassical facades. With his European-influenced vision of “Paris on Lake Michigan,” Burnham wanted to steer Chicago away from the helter-skelter development of the 19th century.

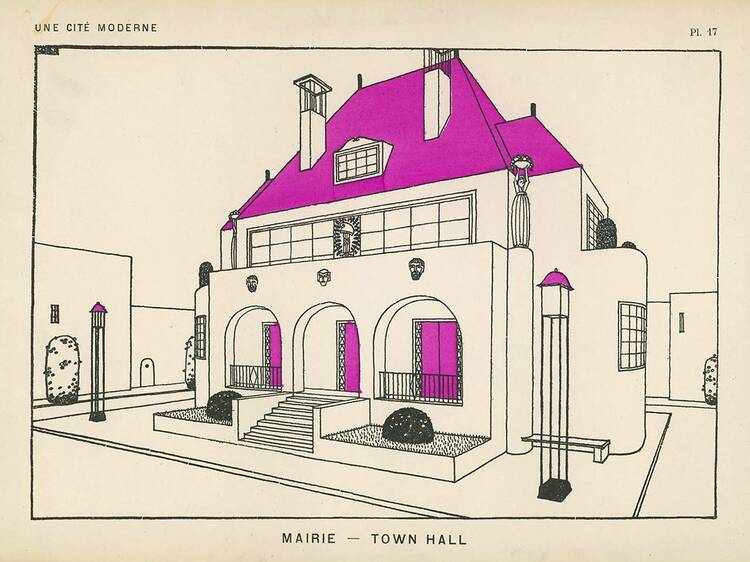

As the exhibition continues, these Beaux Arts renderings quickly give way to more modern expressions. The usual textbook examples of early modern city planning are represented and include notable designs by Eliel Saarinen (1873–1950) and Tony Garnier (1869–1948). More space is devoted to the winning urban plans for the Canberra design competition by Chicagoans Walter Burley Griffin (1876–1937) and Marion Mahony Griffin (1871–1961). Both the Griffins worked for Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) whose Wasmuth Portfolio, published in Germany in 1910, is often credited with beginning the dialogue between avant-garde American and European architects. (Several pages from the Wasmuth Portfolio are on view here.)

But what stands out in this show are unexpected works by more obscure artists, including the Czech artist Wenzel Hablik (1881–1934). His Schaffende Kräfte (1909) presents a series of etchings depicting fantastical landscapes where architecture and nature are fused into singular expressions. Hablik’s crystalline and organic forms predict later built works by German expressionist architects, such as Bruno Taut. But Hablik’s drawings also reflect the era’s creative zeitgeist, where architects and artists yearned to merge cities with natural landscapes (a hallmark of the Griffins’ designs for Canberra).

The exhibition ends on an opposite note with the Orwellian renderings of Ludwig Hilberseimer (1885–1967). Here, nature has been stripped away and replaced with rows of severe, modernist structures. In Das Kunstblatt (1922), Hilberseimer’s monochromatic buildings, bridges and highways presage the glass and steel minimalism of Mies Van der Rohe. Only 15 years separates Burnham’s colorful, sunny renderings from Hilberseimer’s stark “future vision." Yet each architect imposes his own regimented order onto the cityscape. A bit of both can be seen in Chicago’s cityscape today.

While walking through the galleries, I wondered how accurately these drawings did—or did not—predict the future. How much of today’s Canberra conforms to the Griffins’ winning designs? What aspects of the Burnham Plan were actually built in Chicago? It would have been instructive if the exhibition had included images—even small thumbnails with the label copy—to give museum visitors a better idea of how yesterday’s visions became today’s realities.