On returning from his first trip to Japan in 1905, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) brought back crates of Japanese art to Chicago. He became a serious collector of artists like Hokusai, Hiroshige and Utamaro, and a dealer of Japanese woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e. When Wright was short on cash or owed debts (which seemed to be most of his life), he sold prints and other works of Japanese art such as Buddhist sculpture. Subsequently, pieces from his collection can be found today in museums across the U.S., including the Art Institute of Chicago.

A new exhibition, “The Formation of the Japanese Print Collection at the Art Institute: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School,” explores Wright’s central role in the Art Institute’s early acquisition of Japanese woodblock prints. It also revisits one of the first exhibitions of Japanese prints at the museum, a 1908 Wright-designed show that included frames and stands by the architect himself.

The Art Institute’s Janice Katz, curator of Japanese art, and Ellen Roberts, curator of American art, collaborated on “The Formation,” selecting works from the departments of Asian art, architecture and design, and the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries. Included are Japanese prints originally owned by Wright, archival photographs of the 1908 exhibition and architectural drawings from Wright’s studio.

A substantial part of the show looks at the aesthetic influence of Japanese prints and scroll paintings on the presentation renderings of Wright’s studio. Shortly after his return from Japan, the architectural drawings depicting Wright’s famous prairie houses changed. The perspective sketches began to include conventions of Japanese prints: off-center compositions, flattened forms of trees and other landscape features, and the use of large areas of empty space.

Wright’s draftsmen were continuing a conversation between East and West that had started in the 19th century. The vibrant colors, asymmetrical compositions and flat imagery of Japanese woodblock prints had a profound influence on Western artists, most notably the French Impressionists and Vienna Secessionists.

Into this artistic dialogue steps an unexpected star of the Art Institute’s show, Wright’s most gifted drafter, Marion Mahony Griffin (1871–1961), who combined Japanese artistic conventions with Western perspective drawing to create the signature style of Wright’s presentation renderings. In his 2011 book Marion Mahony Reconsidered, Northwestern University professor David Van Zanten writes that Mahony Griffin’s presentation work “was among the most extraordinary of her time.”

A Chicago native, Mahony Griffin graduated from MIT with a professional degree in architecture (the second woman to do so) and was the first woman to pass the Illinois architects’ licensing exam. Along with her husband, Walter Burley Griffin, she famously designed the urban plan of Canberra, Australia’s capital city.

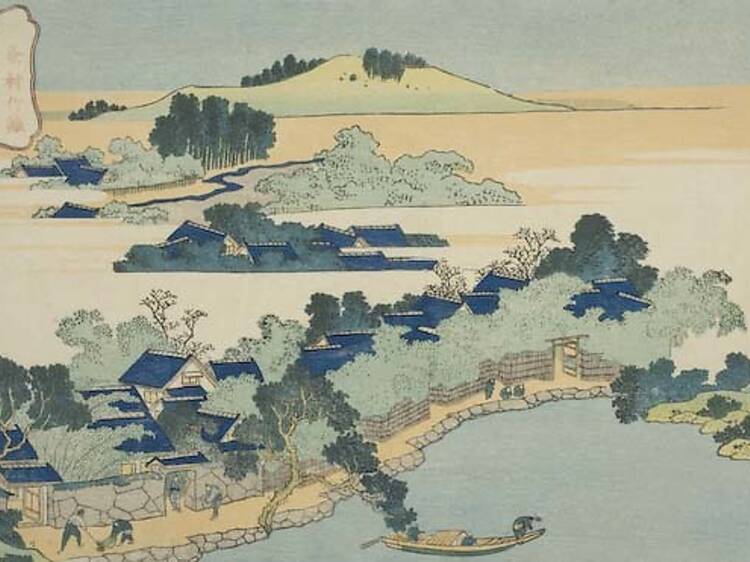

“The large-scale renderings that she created are fantastic,” Roberts says. Her Perspective View of Rock Crest / Rock Glen, Mason City, Iowa (1912), shown in the exhibition, owes a debt to Hokusai’s Sacred Fountain at Castle Peak (pictured, 1832), once owned by Wright. Here, she employs a bird’s-eye view, similar to Hokusai’s, of a suburban development designed by her husband. Mahony Griffin was not copying Hokusai’s style but rather synthesizing Japanese pictorial conventions with Western drawing techniques to create something new. Her work reflects the artistic innovation of an era of cross-cultural pollination.

“The Formation of the Japanese Print Collection at the Art Institute: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School” opens at the Art Institute of Chicago Saturday 18.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article included a misstatment from a source that has since been corrected.