The Art Institute of Chicago’s “Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective” has seen lines out the door—even on a recent Monday. An AIC publicist tells me it’s the museum’s “most popular show in the Facebook era.” For its final four days, over Labor Day weekend, the exhibition’s hours will be extended into the evenings (5–8pm). None of which is surprising, given that Lichtenstein’s paintings have long been recognizable and accessible to museum audiences. Developed in the early ’60s, his signature style elevated comic-book graphic techniques to high art. But the exhibition, curated by James Rondeau, moves beyond these familiar images to include the artist’s lesser-known “brass-n-glass” sculptures, riffs on art-history icons and landscapes in the Chinese style.

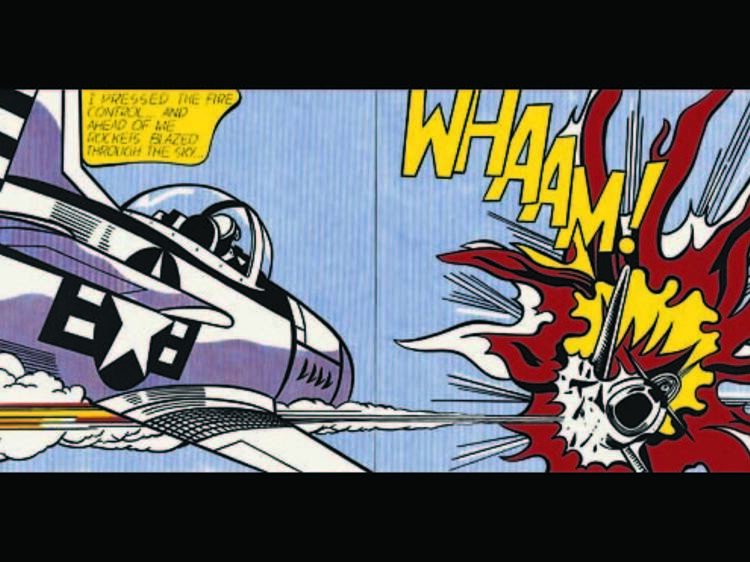

The show opens with classic works like Whaam! (pictured, 1963). Masterpiece (1962) displays Lichtenstein’s tongue-in-cheek humor: A beautiful blond croons to a chiseled-faced artist, “Why, Brad darling, this painting is a masterpiece! Soon you’ll have all of New York clamoring for your work!” Here Lichtenstein expresses his (and every artist’s) ambitions in a self-deprecating, funny way.

Much of the work straddles the line between fine art and kitsch. Falling in the former category, Seascape (1964) eschews representational forms in favor of fields of dots that suggest traditional landscape elements. This painting is as sublime as any created by Mark Rothko. But for every Seascape, there’s a Landscape with Figures and Rainbow (1980). Despite the latter’s formidable scale and Old Master–influenced composition, the experiment falls flat, literally: It lacks the texture, depth and light of more successful works like the Monet-inspired Rouen Cathedral, Set 5 (1969).

Before his death in 1997, Lichtenstein experimented with the conventions of traditional Chinese landscapes. Till the end, he pushed the boundaries of his own comics-inspired visual language.