Every family has its bit of idiosyncrasy, the odd meal or the slightly off-kilter holiday ritual that, when looked back upon in adulthood, registers as bizarre. Wenguang Huang has yours beat. As a nine-year-old growing up in China, he began sleeping next to his grandmother’s coffin.

In 1973, after turning 71, his grandmother—in a dramatic manner reserved for the elderly—declared she was dying, and wanted to be buried with her deceased husband. Though she would live another 16 years, his father immediately went to work on building her a coffin, and stored it in his eldest son’s bedroom. The family referred to it as a “longevity wood.”

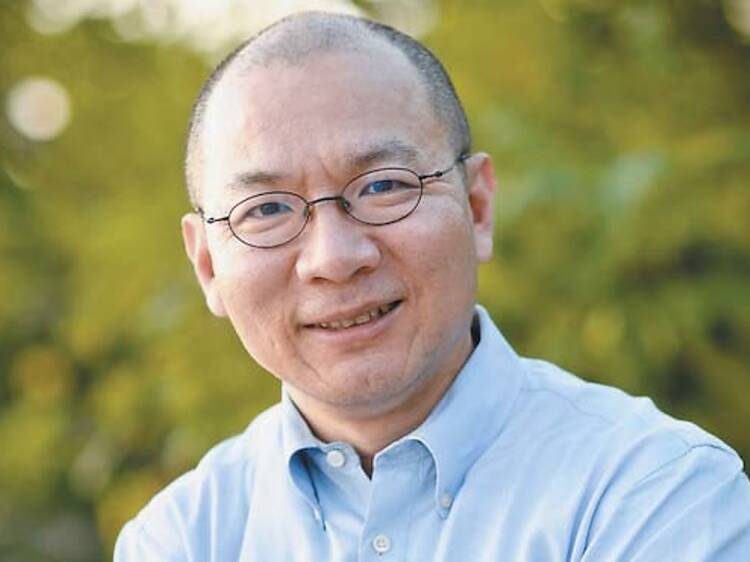

“As a kid, it was just something you accepted; it never struck me as strange,” says Huang, 47, who for the last 20 years has lived in Chicago. “But looking back, I can see the imprint on me. I was always asking questions about mortality, and for years and years I was very interested in funeral culture.”

That imprint also provides the central image of Huang’s first book, the memoir The Little Red Guard (Riverhead, $25.95). Huang tells the story of three generations of his family, straddling the Maoist era with the traditional grandmother on one side and the post-Maoist, Westernized Huang on the other. In some respects, the book is a domestic drama: Hopelessly devoted to his mother, Huang’s father spends much of his time and money accommodating her. Telling quote: In 1988, when Huang takes his dad on a trip to Shanghai, his father mourns not being able to travel more. “I had to focus my financial resources on raising you children and preparing for your Grandma’s funeral,” he says. The father’s dedication to his mother wears away at his marriage, as Huang’s mother and grandmother needle each other, and the family adjusts to shifting political climes in China.

Though this is his first book, Huang has translated several works from Chinese to English, and spent years as a journalist writing for various papers and magazines. He now works a corporate job downtown, but freelances for the likes of The New York Times and Christian Science Monitor. He says he had intended to write what he calls a “China book,” a story about the people of China that is not freighted with current politics. While in the subtext the constant clashing and melding of cultures animates the family arguments, the story remains largely within the walls of his boyhood home.

“Right now, there are a lot of books about China written by two groups: people who were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, and Western reporters providing their perspectives of China,” he says. “But—I know this is a cliché—writing it was an act of self-discovery, and I felt I learned so much about my parents.”

Both of Huang’s parents emerge as tragic figures: the husband chained to his obligations and the wife left disregarded. His father dies a year before the grandmother, and Huang’s mother dies before the publication of his book, estranged from her son.

“I went back to China, to my parents’ tomb,” Huang says. “In traditional Chinese culture, if you send something to the dead, you burn it. So I burned the book at their tomb, and said, ‘I hope you read the book, and like it.’ ”

Huang reads from The Little Red Guard at the Book Stall Thursday 26.