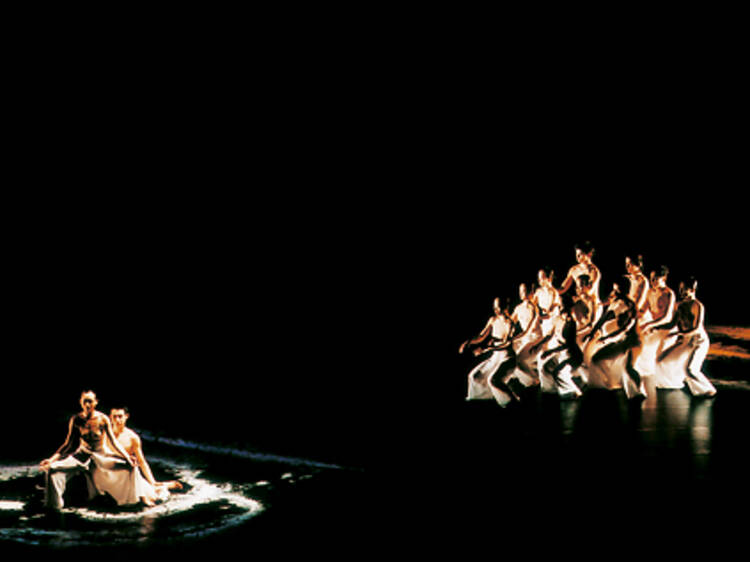

When choreographer Lin Hwai-min founded Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan in 1973, its emphasis was mostly on dance-theater adaptations of well-known works of Chinese literature, folklore and opera. The company’s global reputation exploded, though, when Lin moved away from narrative in favor of less culturally specific pure-dance pieces. 1998’s Moon Water, by many accounts Lin’s masterpiece, receives its Chicago premiere at the Harris Theater Friday 22.

You’re widely credited as having started the Chinese-speaking world’s first contemporary dance company. How has the Asian dance scene evolved since the ’70s, and where do feel it can go from here?

I’m not in a position to answer this question, sir. [Laughs] I really don’t know that much about its development and all that, but now there are modern dance companies in every single Asian country, I believe. I don’t know about Cambodia. No, even Cambodia has started one! Yes.

Stories are in your blood—you’re equally well-known in Asia as a writer—so why did you feel the need to move to abstract work, and why has the shift been so absolute?

Because of my background as a writer. Yes, I choreographed adaptations, but to me dance is not about meaning, it’s about bodies in movement, dynamics and energy. It took me about 20 years to erase the words in my mind, but I like my works better now and appreciate things no longer needing to play roles, which I think limits the possibilities of movement. Another reason, I think, is because I live by a big river, right outside my door, which calms me down and makes me see things differently.

Is dance a more pure form of communication than language?

Yes. I like that an audience of a thousand people leaves the theater with a thousand different versions of the work. That’s beautiful.

You’re still an avid reader, though. You describe yourself as a “garbage can” when it comes to books.

I am! My dancers are like animals, hungry for movement, and I’m a person still hungry for words, even though I don’t think that way anymore. So I keep reading. [Pauses] I’ll tell you how I created Moon Water.

Please do.

It’s a good example, actually. I asked my dancers to close their eyes, sit down and meditate, using an ancient form of qigong. They hated me—[ Laughs]—because they wanted to move, so I choreographed something for them to dance, like a carrot for a horse. I used the music of Johann Sebastian Bach but applied all these principles, the breathing, the qigong—not routine dance exercises. We were in Munich at the time, and one day I was walking through downtown and there was a long stretch of mirrors on the second floor of a building, set in a downward tilt so that they reflected the street, and I said, “Oh, wouldn’t that be nice, to have mirrors like that!” And there you go. I never planned, never had a script. When things click together, it’s beautiful, and when they don’t click together, I labor. [Laughs]

What led to to specifically led you to choose Mischa Maisky’s recordings of the Bach pieces?

That’s a very good question. The way Mischa plays, he exaggerates each line—it’s very low, and sounds heavy and stretched. The time he takes to play each musical line allows us to go into it, to draw its energy, and it feeds the body. I like the way he breathes through the compositions.

Is there “more” in his playing than in other cellists’?

Well I’m not a musician, I’m not an expert, but I feel like most cellists play Bach’s suites in a baroque style—of course, right, it’s baroque music—but Mischa plays in an almost Romantic way: Stronger, heavier, going on and on into a feeling. I use the recordings he made in the ’80s. We got to perform with him live last year, actually, which he enjoyed very much.

You’ve called the creative process “scream-inducing.” Is reviving an existing work like Moon Water any easier?

It’s painful to watch my work because I always find little flaws here and there. But they’re still a part of what it is. I can’t really “fix it”—I don’t know how to better it. I do a little surgery, a little face-lifting, but there are still some things that feel not right. It’s painful and it’s wonderful. Most of the original principals [in Moon Water] are still in the company, minus only one or two. They’ve all matured so much—there’s so much power in their bodies. Kung fu has a double meaning in Chinese: One is the ability to kill, as people know, but it also means the time you spend on one thing. My dancers have better kung fu now than they did 11 years ago.

You restaged Smoke for the Zurich Ballet, but that was an unusual move for you. Do you have plans to distribute your work among other companies? How do you feel about licensing?

It’s hard to find another company to perform a piece like Moon Water because nobody moves like we do. [Laughs] Smoke also has a vocabulary of its own, but it’s not as heavily based in what we do at Cloud Gate, so we could restage it. I’m still receiving invitations to choreograph on other companies every year, but I just don’t have the time, because I’m running two companies. We have a second company, too.

Cloud Gate 2.

Yeah, so at this moment there isn’t any time, immediately, to do that. I’m always fighting for time to sleep, especially after our studio burned last year.

That was very tragic.

Such a devastating accident. Fortunately, it happened during the Chinese New Year holiday, in the evening, so nobody was there. But we’ve finally settled upon a new architectural design, after almost two years, and have started building our new complex. All of this eats up my time, and I don’t see a way out, frankly! [Laughs]

The international dance community showed a lot of support when you lost your building, that at least must feel good.

Indeed, more than 5,000 donations came. All of a sudden, I felt as though I had 5,000 shareholders in my company, and I don’t want to let them down. I’m obliged to fulfill our collective dream. Another reason to build the complex is so that the company will survive after my final curtain call because, even after 36 years, Cloud Gate remains the only full-time dance company in Taiwan. I would like to see this go on without me. We just signed a lease with the government for 50 years. I think, probably a couple of years after we move into the new complex, it’s time for me to go away. [Laughs] It’s very possible.

This summer’s passing of Merce Cunningham affected you very deeply—you repeatedly cite him as your greatest influence.

Yes, yes. It was a very tragic summer, first Pina [Bausch], then Merce. Merce let me know that there is always a new frontier to open, and the biggest impact Pina made on me was that she did such wonderful theatrical work. I moved to the other extreme, which is the pure dance form that I’m doing now.

Your work is pitched between theirs—I can see the influences coming from both sides, even though the two of them didn’t have much in common.

True, true…it’s wonderful to stand on the shoulders of the giants! [Laughs] I saw The Moor's Pavane performed by [José] Limón himself, in Taiwan when I was 14 or 15. I literally had my mouth open. I thought, “Oh, my God–that’s modern dance!” [Laughs] And I like Balanchine’s later works like Mozartiana, like Davidsbündertänze. The dancers go into a nightmarish trance, an almost crazy place. I like Graham’s early pieces, and I like several works by Forsythe—the ones that don’t involve speaking. [Laughs] Pina’s early works are simply amazing. Her manager and I were talking not long ago—she and I shared the same agent in the States—and it amazed me that her company was never in Chicago. Is it true?

I believe so.

But, before anything could be done, she’s gone. When I returned home from the Chekov International Theater Festival in Moscow, I received the news that Pina had passed away. I immediately went back to Moscow to be with her company, who were booked to close the festival. It was the only way I could say goodbye to her. She directed three dance festivals in Germany and invited us each time, always came onstage to present bouquets, and would arrange a big dinner for everyone afterwards. We didn’t talk that much, but we were both smokers. We’d be sitting outside smoking together and, when people passed us, Pina would tell them that we were “bad kids,” and then we’d go on smoking, quietly. Some people have drinking pals, but rarely do you find a smoking pal, especially nowadays. Merce and Pina were the king and queen of the dance world, but were both so humble. Soft. Warm.

Do you have anything that you want your audiences to have in mind before they enter the theater?

To everybody coming into any dance performance: Just relax, and try to have a pair of fresh eyes, so you can really absorb. The theater is usually so quiet during Moon Water that everyone starts to breathe together, and that’s a wonderful thing to experience.

Moon Water splashes into the Harris Theater Friday 22 and Saturday 23.