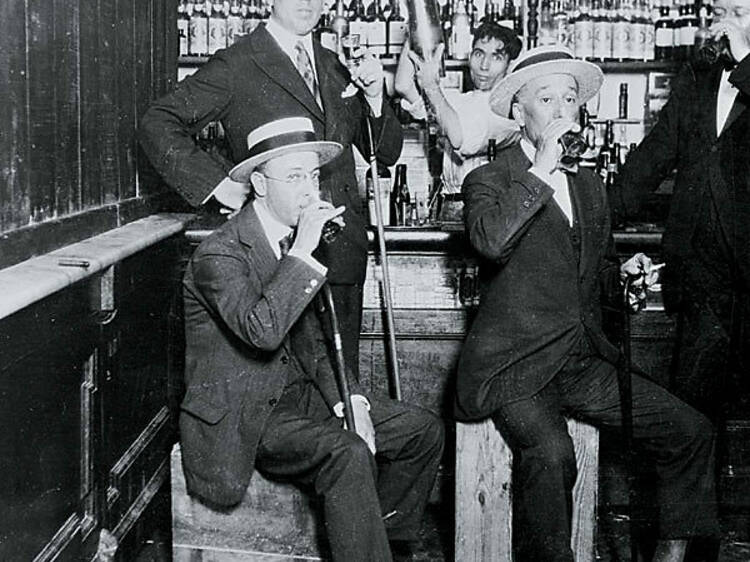

Al Capone arrived in Chicago with two areas of expertise: gambling and prostitution. But he was an entrepreneur, and like any good businessman, he was always looking for the next big thing. Arriving in Chicago just as Prohibition was getting under way, he quickly got into the business of making, distributing and selling alcohol. There were areas in America that followed the Prohibition laws of the 1920s to a T. Capone and his cohorts made sure that Chicago was not one of them.

If Chicago’s history with drinking was any indication, the city didn’t mind Capone’s enterprise. Alcohol was never much of a demonized commodity here; before Prohibition, restrictions were among the loosest in the country (although the Women’s Chrisian Temperance Union was a major force in Evanston). There was no minimum drinking age and no restrictions on buying on Sunday. In fact, says John Russick, senior curator of the Chicago History Museum, if it had been left up to us, “I don’t know that Chicago would have passed a Prohibition law.”

So it’s doubly confusing that 75 years after Prohibition was repealed (the official anniversary is Friday 5), bars keep on opening with intentions to relive it—or at least an imaginary version of it. Every few months, a new bar opens that purports to be a descendent of speakeasies, whether because it has a hidden entrance (Stay; 111 W Erie St, 312-475-0816), serves Prohibition-era cocktails (The Violet Hour; 1520 N Damen Ave, 773-252-1500) or simply has a turn-of-the-century aesthetic (1914; 3525 N Clark St, 773-472-0900). The Prohibition these spots are inspired by is one of secret passwords, trap doors and hidden passageways. And though these things may have been present to some extent, they hardly tell the whole story.

Speakeasies still exist, but many so-called speakeasies aren’t exactly following the rules. So in the interest of setting the historical record straight, we offer a few facts that will help when trying to determine a real speakeasy from one that’s assuming the pose.

Speakeasies weren’t necessarily secret. Speakeasies primarily came in two forms: There were speakeasies like that at the Green Door (678 N Orleans St, 312-664-5496), which was a clandestine club hidden in the basement. Then there were speakeasies like the Green Mill (4802 N Broadway, 773-878-5552), which was a legitimate venue for live music that illegally served alcohol in plain sight.

Speakeasies were run by criminals. Speakeasies “came in all shapes and sizes,” Russick says. But “people didn’t just decide that they were going to open a bar in their basement...unless you were ready to take on business with Capone.” In other words, speakeasy owners were not regular citizens opening a business. If you were running a speakeasy, you were part of—or a puppet of—a gang.

They didn’t look like bars. Most clandestine speakeasies were in basements, warehouses and apartments. They weren’t fully appointed bars hidden behind rotating walls.

The cocktails were not fancy. Serving alcohol wasn’t the only thing that was outlawed during Prohibition; producing it was, too. The bathtub spirits were, well, made in a bathtub—and tasted like it. That’s why the buzzword in modern mixology is pre-Prohibition cocktails—Prohibition was the killer of cocktail culture, not an impetus for it.

There were no lines to get in. Unlike the “speakeasies” of today, they realized this may have given something away.