They entered swiftly and unannounced, like anybody on a surprise inspection. Point after point, everything checked out. But when the city inspectors reached the basement, they stumbled upon the hub of a painstakingly precise operation. The suspect in question was not some drug kingpin or organized-crime ringleader. It was Lula Cafe, a restaurant dealing in stuffed French toast and hand-cut pastas. And its offense? Canning.

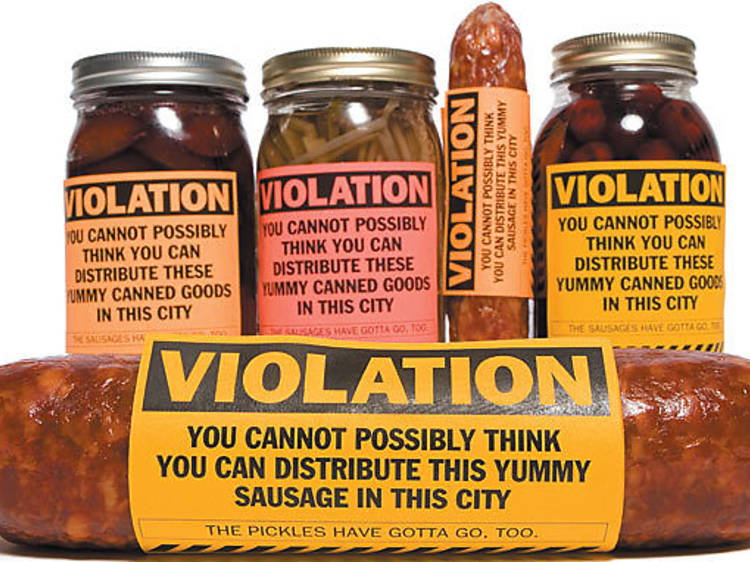

The brigade of cooks was given no choice. They took turns lugging close to 200 quart-size glass jars from their subterranean pantry into the back alley, where an inspector watched as they emptied the contents of each into the Dumpster—not because anything was found to be harmful, but solely because Lula didn’t have approval to practice what the government calls “modified atmosphere packaging.” The cooks were ordered to pour bleach over the preserved stone fruits, roasted peppers and multicolored beets, a standard procedure that, according to Frances Guichard, Chicago’s Food Protection Program director, is meant “to denature the product, to prevent anyone from taking it out of the garbage and potentially getting sick from eating it.”

While one inspector stood watching, he attempted to sympathize with Lula’s owner Jason Hammel. “He talked to me about how I must have trained in Europe and how ‘us European guys’ do things in a way that aren’t really done in America,” Hammel recalls. “‘They hang ducks in the window over there’ he said. ‘But you just can’t do that here, as much as I know you European guys are all about quality.’”

The inspector got it about half right. Hammel has never worked in Europe, but he is all about quality, and he’s part of a growing legion of American chefs reviving practices typically associated with the Old World (or grandma). Here in the land of a growing season so brief you could blink and miss it, chefs rely on canning and curing to extend local farmers’ larders, stockpiling like squirrels readying for winter. And as a nod of respect to both pig farmers and the pig itself, many chefs have returned to the whole-animal ethic that brings glory from guts, turning offal and other throwaway parts into delicious edibles via charcuterie. Pâtés, terrines and fresh sausages—which take shape under refrigerated conditions—are perfectly acceptable to the health department. But when it comes to curing or canning, both intended to make products shelf-stable, city inspectors begin to take notice. In the last few years, they have begun to enforce tough regulations covering restaurants that put up preserves. “There’s a whole lot more to it than a blanket yes or no,” Guichard acknowledges. “It’s looking at the science of handling a product like this to prevent clostridium botulinum, which can be deadly.”

Before a restaurant can jar a single green bean or cure a pound of salumi, the chef (and anyone else who’s getting his or her hands dirty) is required to take a HACCP course. Commonly referred to as “Hassip,” the acronym stands for Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points. “I took a class, thinking ‘I’ve been cooking 35 years, I can do this on my own,’ but it isn’t quite that simple,” says John Coletta, executive chef of Quartino, a 600-seat restaurant that serves housemade duck prosciutto and capocollo to nearly half of the 2,000 people who dine there on any given day. “But I don’t know the little details that the federal government, the state of Illinois and the City of Chicago would enforce. That’s a whole other business, and you need someone to guide you through it.”

That someone, known as a HACCP consultant, charges around $15,000 to produce a plan comprehensive enough to earn approval from both the city and state. For that fee, he or she will first tell you to sink an average of $50,000 into building a separate processing space—the Quartino crew dropped close to 100 grand on a drying box and production area outfitted with a state-of-the-art dehumidistat. As Coletta says, “This is not an ordinary cooler. This thing essentially re-creates the microclimate of Northern Italy.” That, and it passes inspection.

HACCP consultants keep meticulous logs tracking every moment of the process, from when the pig or produce enters the back door to the final reward of consumption. “Monitoring time and temperature, testing pH levels, taking moisture readings, sending samples off to labs for bacteria testing…200 pages of data is what you pay the consultant for,” says Jared Van Camp, chef of the newly opened Old Town Social, whose in-house salumi program is such a linchpin of the operation that a separate charcuterie bar was built to showcase his spicy sopprassata and garlicky Toscano. The bar’s anchor, a vintage Berkel hand-crank slicer Van Camp scored on eBay, is churning through the housemade cured meats on a delicate trial basis while Old Town Social awaits their city and state approvals, a process that could take months with no guaranteed outcome. “It’s frustrating because the USDA now says that semi-dry sausages aren’t low enough in pH and low enough in water activity to hang at 50 to 55 degrees, which is what I’d like. You have to hang at 40 degrees or below, which doesn’t change quality, but time. At 40 degrees, it takes two months for my salumi to be ready as opposed to one month at a higher temperature.… I understand the need for food safety, but there’s no reason the FDA shouldn’t accept the practice as Europeans do. We look like stupid Americans with our salumi in coolers.”

The issue extends beyond Chicago. Around the same time Lula Cafe was forced to toss its pantry supply, NYC health inspectors ordered chef Cruz Goler of Lupa to dispose of several thousand dollars’ worth of cured meats. On the opposite coast, Chris Cosentino of San Francisco’s Boccalone has seen an uptick in interest from the health department (“They’re trying to set up protocols, but [they] don’t understand the process,” he says) and Portland, Oregon’s Higgins Restaurant was cited for its canning, curing, smoking and cheesemaking. “What they’re doing now is trying to scare people because it costs time and effort to monitor it,” Higgins says.

The chefs intent on continuing these intensely regulated techniques have two choices: hire a HACCP consultant to get approved or go underground. An award-winning local chef who has served his canned and cured foods for years without permit, admitted—under the condition of anonymity—that the crackdown prompted him to look into gaining approval, but lack of space, funds and time have held him back. “I’m incredibly nervous about it, so I go above and beyond with following USDA regulations to ensure diners’ safety,” the chef said. “The whole idea of eating local and the need to preserve and extend the season is so crucial to what we do it would be devastating if we had to discontinue this.”

Adds Hammel of Lula, “Clearly we’re at a point in time where there is a conflict between [the government’s] idea of safety and our idea of deliciousness.”