The first time Topolobampo chef de cuisine Brian Enyart stepped foot on the Kilgus family farm, it was, ostensibly, to taste its goat milk. He was already downstate to visit with Spence Farms (renowned for their ramps), and the farmers there had convinced him it would be worth trying.

The goat milk was good—Enyart bought some on the spot and started using it at the restaurant. But what really interested Enyart was something more substantial. He pointed to the Kilguses’ pet goat.

“We’re looking for that,” he said.

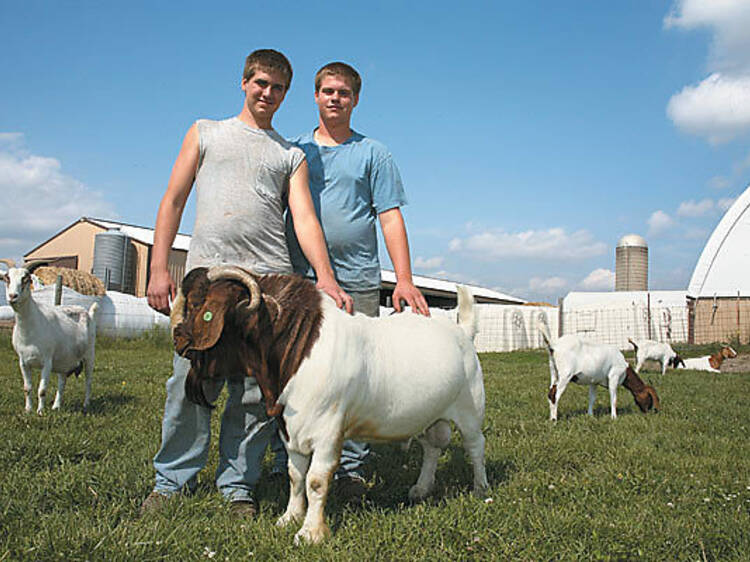

The Kilgus boys, Justin and Trent, overheard this and snickered. The thought of selling the actual goats had never occurred to them. Who would ever want them? And the thought of actually eating the things was laughable to them.

Three years later, the boys don’t find the goat business so funny. After agreeing to raise some goats for Enyart, the brothers realized there was a market for the stuff. And though at the time Justin was only 15, and Trent was all of 12, they applied for and received a Frontera Foundation grant. With that start-up money, they started Pleasant Meadows Farms, currently the goat supplier du jour for Chicago chefs.

The boys were no strangers to farming, of course. Growing up in Fairbury on a third-generation farm, they couldn’t avoid it. More to the point, they’ve never had any inclination to even try to avoid it. “We developed the goat business to find a way to come back to the farm,” Justin says. (His parents’ dairy operation isn’t big enough to employ the brothers full time.) “I guess we just take to farm life.”

Now 18, Justin finished his last semester of high school in December, and the afternoon we spoke he was talking on a cell phone from the farm; in the background I could hear the constant, unmistakable whine of goats. In theory, his time at home frees him up to do all the chores associated with running his goat business. But he’s happy to leave that to Trent, now 15, for whom school apparently does not act as a deterrent to running a business. Trent checks on the goats before classes start. Then he rushes back home from school to check on them again.

Freed from those duties, Justin’s goal is to market the product. But the truth is the product has done a pretty good job of marketing itself. Before Pleasant Meadows, a lot of goat available to Chicago chefs was from out of state, which meant it was older by the time chefs got their hands on it. A Pleasant Meadows goat, on the other hand, is delivered to restaurants like Naha, Vie and Carnivale just two days after it’s slaughtered. It also happens to have a great story behind it. The goat has “roots in our community,” Enyart says. “It’s a story we as cooks and chefs can connect to.”

It helps that the goat also tastes good. Since starting their business, Justin and Trent have come to know what good goat tastes like (they’re particularly fond of Enyart’s barbacoa), and they create highly controlled conditions to ensure their goats are flavorful. They decided to raise only Boer goats, an heirloom variety known for the fine meat they produce. They breed all their goats themselves, and they raise the goats strictly on pasture, where the animals eat nothing but grass from spring through fall, and then the family’s homegrown hay in the winter. The one exception to this is the kids—the baby goats—which are fed only their own mother’s milk before being slaughtered and sold as sucklings.

Those kids make up half the brothers’ business, mostly thanks to the Bristol and Topolobampo, the boys’ biggest clients. Asked if it ever gets difficult to see so many cute baby goats go to slaughter, Justin doesn’t show a lot of emotion. “Goats can be ornery,” he says dismissively. “Some of them don’t want anything to do with you.” But he isn’t a heartless, grown-up businessman just yet: He admits that he keeps the gentler goats—the females—on the farm for breeding purposes. And the pet goat that started it all? It never entered the business.