[category]

[title]

Skip the crowds recreating “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” and check out these under-the-radar picks.

With nearly 300,000 works on display, you could spend years learning the ins and outs of the Art Institute of Chicago’s sprawling halls. Still, despite the museum’s massive collection (or maybe because of it, depending on your tendency toward indecision), it’s easy to get stuck traversing the same well-worn path through the Impressionist galleries, or staring even closer at the thousands of dots comprising “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884,” or snapping a pic with yet another van Gogh... you get the idea.

If you’re eager to see something new but don’t know where to start, consider taking a little expert advice. We spoke with Robyn Farrell, associate curator in the Art Institute’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, to learn about some of her favorite lesser-known highlights from the museum’s collection—and why they’re worthy of a closer look during your next visit.

Hitoe, Roger L. Weston Gallery 108

Head to Gallery 108 on the museum’s first floor to see this elegant hitoe—a light, unlined kimono worn in the summer—patterned with leaves and yellow water irises. The garment, which was produced in Japan during the beginning of the 20th century, features curvilinear shapes that suggest a potential influence of Art Nouveau, although the naturalistic theme is classically Japanese: “The undulating pattern in this garment gives a sense of the reflection of water,” Farrell explains.

While you’re there, Farrell recommends making a circuit around the surrounding galleries, which are full of centuries of art from China, Japan and Korea. “They’re very contemplative and have many beautiful objects,” she says.

Color(ed) Theory by Amanda Williams, Architecture and Design, Gallery 285

What color is poverty, and what color is gentrification? Chicago-based artist Amanda Williams sought to answer those questions with her series Color(ed) Theory, in which she enlisted friends, family and neighbors to help paint vacant and condemned homes in Englewood in an array of pointed colors. “The color palette that the artist chose, I believe she referred to it as ‘culturally-coded monochromatic colors,’” Farrell says. “These were drawn from a palette of colors that were typically marketed toward Black consumer products,” including candy pink (for Pink Oil Moisturizer) and bright reddish orange (for Flamin’ Hot Cheetos).

By infusing color into these otherwise untended homes, Farrell adds, Williams elevates them to sculptural objects, inviting the viewer to consider the legacy of redlining and disinvestment in Black communities. “In looking at color and its relationship to architecture, Williams is prompting questions about race, value and place,” Farrell says.

The Past and Present by Gertrude Abercrombie, Art of the Americas, Gallery 262

Gertrude Abercrombie was a key figure in the Hyde Park arts scene during the mid-20th century, painting self-portraits, interior scenes and jarring, dream-like landscapes. This small oil painting of a muted, gray-toned bedroom blends realism with personal elements, a signature of her style: “[Abercrombie] was part of a group of Midwestern surrealists, who of course borrowed from the tenets of European surrealism, looking at conscious and unconscious states, but bringing in their own personal touches to the movement,” Farrell says. “In Abercrombie’s case, she brought in a lot of personal notes into her paintings.” Take note of the letter depicted on a table—a recurring motif in Abercrombie’s work—and a miniature version of one of the artist’s other paintings hanging on the back wall.

Rhyton (Drinking Vessel) in the Shape of a Donkey Head, Arts of the Ancient Mediterranean and Byzantium, Gallery 151

Maybe you’ve already seen that weird statue of a baby satyr wearing a theater mask nearby, but if you’re walking through the Arts of the Ancient Mediterranean and Byzantium, this equally bizarre donkey wine glass is a can’t-miss. “Many of you may have passed by [this work] on your way to the cafeteria or other spaces in our museum,” Farrell says. “It’s a vessel in the shape of a donkey head, complete with very detailed eyes, nose, even teeth, and a naked satyr around its neck. Looking at this cup, there’s really no way for someone to put it down, so it’s always something I like to revisit, not only because of its age—it dates back to 470–480 BC, and part of its association with the wine god Dionysus—but also just to think about how it might have been used.” (Hint: For chugging wine.)

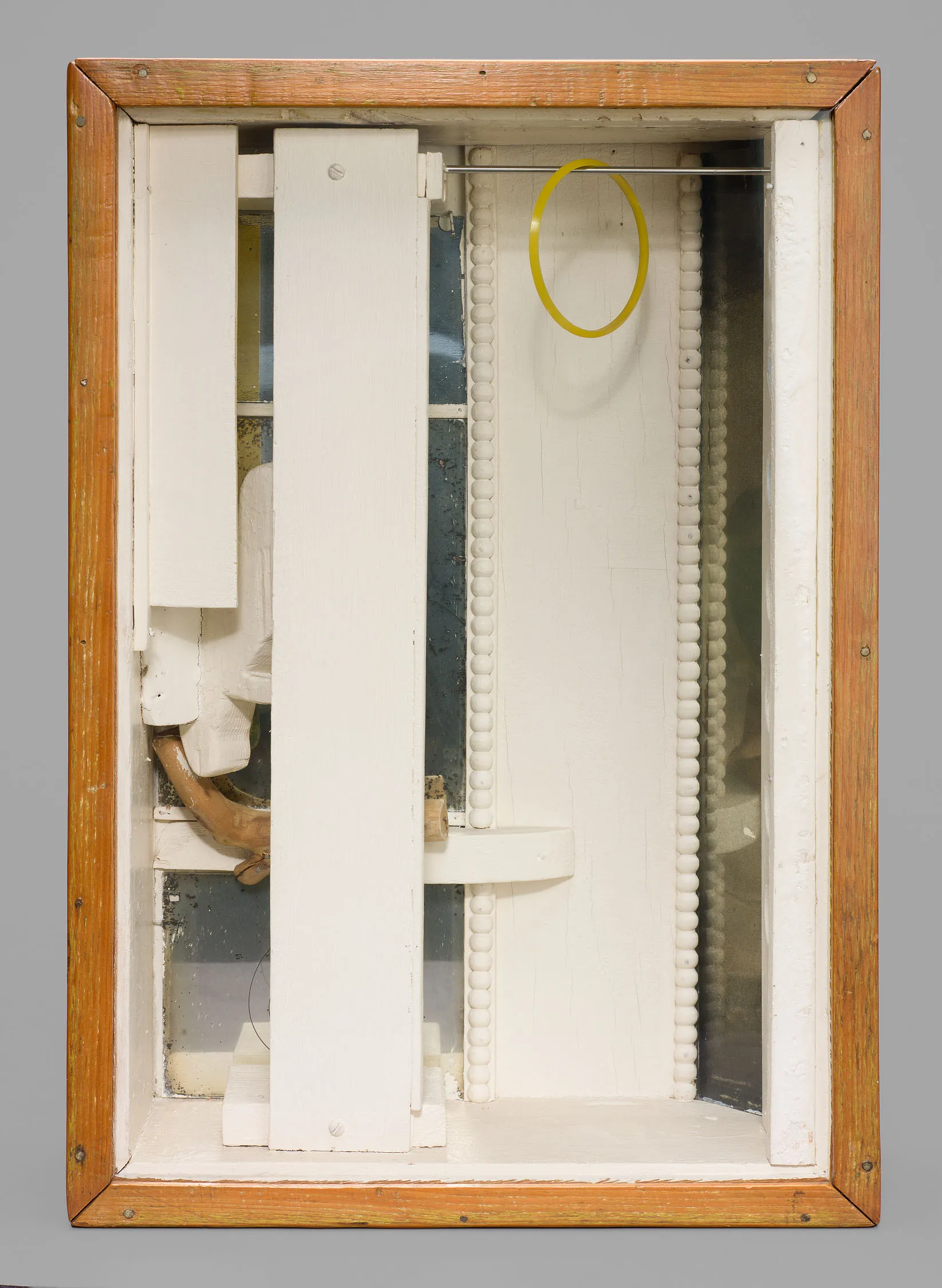

Yellow Chamber by Joseph Cornell, Modern Art, Gallery 397

Take a look at this box. What’s lurking inside? If you can’t immediately tell—especially from looking at the 2-D image—that’s part of the point. “Joseph Cornell was an American visual artist and experimental filmmaker known for assemblage and really elevating the idea of a box construction to a formal medium for art.,” Farrell says. “One of the most intricately-constructed mirror boxes in Cornell’s body of work, this particular work actually suggests an ambiguity of space while also representing architecture as well as a bird cage. Upon closer look, one can actually see that there is a bird hiding behind this vertical piece of wood here.” When you visit the work in person, walk from side to side to see glimpses of the bird from the box’s mirrored edges.

Discover Time Out original video