Chicago-based industrial designer Scott Wilson credits Steve Jobs or, more accurately, an Apple board member, for his million-dollar idea. Inspired by the clock function of the new iPod nano, Jobs mentioned at an Apple event in September that his colleague wanted to use it as a watch. Wilson, along with dozens of other designers, took the bait and mocked up an illustrated design of a watchband that accommodates the nano. He showed his product idea, which he dubbed TikTok+LunaTik, to a few leading accessories companies for backing but no one bit, so he turned to online funding platform Kickstarter to raise money to create the product himself. “The idea is that I have this design that’s just going to sit in my notebook unless I do something with it,” Wilson recalls. “It was more an experiment with Kickstarter to see what would happen if I put a consumer-grade product on [the site].”

New York–based Kickstarter, a less than two-year-old site, offers anyone the chance to raise funds for creative endeavors by “selling” their project’s value to the public. Pretty much any artistically inclined project is fair game as long as it bears no affiliation with a charity. In return for pledging, backers receive a reward, which can range from a “thank you” credit in a documentary film to, in Wilson’s case, a watch kit. And, like Groupon’s tipping-point feature, backers’ credit cards are charged only if the project meets its monetary goal in time (anywhere from one to 90 days). As for payback, 5 percent of the proceeds from a fully funded project goes to Kickstarter; otherwise, use of the site is free.

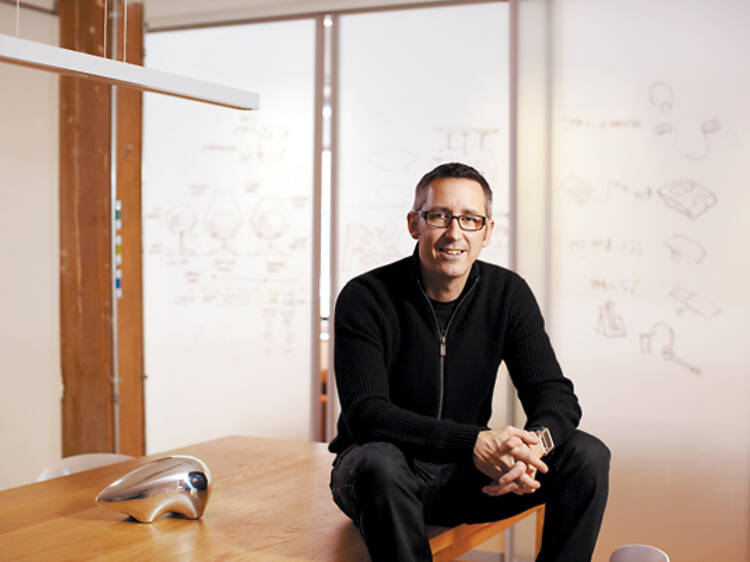

Last November, Wilson set out to raise $15,000 in 30 days through Kickstarter. By 6pm on the first day, he had raised $6,000. A blurb on Fast Company’s design blog, followed by a few other shout-outs on tech-centric sites, helped spread the word. At 6:20pm, when Wilson arrived at a local bar to meet a friend, his wife texted him that his pledge total had shot up to $22,000. Not coincidentally, Gizmodo had blurbed about it 20 minutes earlier. By the time Wilson went to bed that night, eager backers had pledged $60,000, and by the end of his 30-day fund-raising stint, Wilson had raised just under $1 million, the record total for a Kickstarter project to date. “The thing is, its [success] is a confluence of factors,” says Wilson, who runs the design studio MINIMAL and previously worked as a global creative director at Nike. “The time of year, it’s an Apple product, which people love, Kickstarter, tech blogs, social media, design and storytelling—all at once. I was connecting all those dots.”

There’s a lot to glean from his success story beyond the obvious—that people love Apple products and jump at the chance to purchase the latest gadgets. Wilson’s experiment highlights the wealth of people who have the interest and resources to back independent creative projects, particularly if they have something to gain in return. In this new era, you don’t have to be rich or well-connected to support the arts: On Kickstarter, just a $1 pledge makes you a patron.

It’s a shift that’s as necessary as it is empowering—governmental arts funding has all but dried up. In 2007, the Illinois Arts Council doled out $538,755 in grant money to individual artists in Illinois. By 2010, the grant pool dropped to $155,000, and as a result of the delayed cash flow, recipients got their funding as late as a year after their usual delivery date. Even so, the IAC doesn’t see sites like Kickstarter as a threat to its own funding dollars. “The more ways people are giving funds to the arts, the greater the awareness of the [arts’] importance,” says IAC executive director Terry Scrogum. “It often means there are new people getting into the donation process or donating in new ways.”

Like the creative types the site represents, cofounder Perry Chen got the idea for Kickstarter when he realized he didn’t have the funds for an arts oriented pursuit: He wanted to host a music festival in New Orleans but couldn’t drum up the cash. Chen and Yancey Strickler met in Brooklyn in 2005 and began hashing out the concept. They met their third partner, Charles Adler in 2006, and launched the site in 2009 in the middle of the economic apocalypse. In a way, it was perfect timing. Not only was the state of arts funding flailing, but in a depressed economy, people needed something tangible and accessible to get behind before they parted with their money.

Often the biggest incentive for backers to pledge is the reward, which varies according to the amount pledged. “When you think of traditional philanthropy, there’s fatigue,” Strickler says. “You’re being asked to give, but what you get is always unclear. Maybe you get that warm glow of having done something good, but beyond that it’s not sustainable. For us, having something much closer to commerce and patronage—and patronage [is an] idea that’s been present in art forever—that to us seemed like a smart way to approach this that’s honest and up front for everybody.”

Threadless CEO Thomas Ryan has been following Kickstarter since its inception, but it was that straightforward exchange of value—pledge at least $25 and receive a cool accessory in return—that motivated him to make his first pledge on Kickstarter to TikTok+LunaTik. “Yes, I wanted to see Scott succeed,” Ryan says, “but I also like buying cool things you can’t get anywhere else.”

Kickstarter isn’t the only site in the crowd-sourced fund-raising game. San Francisco–based IndieGoGo, launched in 2008, welcomes any kind of campaign, from documentaries to social causes; unlike Kickstarter, creators receive pledge money whether or not they reach their goal. On the niche end of the spectrum, the nonprofit Spot.Us promotes community-driven reporting by commissioning freelance journalists to cover overlooked topics. The content is then distributed through partner news organizations. Similarly, DonorsChoose.org raises money for classroom projects.

For all these sites, one of the many draws is forging a personal connection between creators and backers. That’s where videos, pictures, blog posts and stories come into play. “The place you get that now is the farmers’ market,” Strickler says. “You meet the guy who raised the sheep that gave you this cheese you’re about to bring to a dinner party tonight. That’s a huge motivator. You’re paying to be part of that experience. Culturally and economically [we’re] shifting more toward experiences.”

Because the sites benefit from the projects’ success, too, creators are encouraged to nurture their relationship with backers by keeping them in the loop with progress updates. IndieGoGo promises that the more you update your project, the more love you’ll get from the site, such as appearing on the home page or getting a mention in the IndieGoGo newsletter.

“People are saying [online funding is] a game changer in our industry,” Wilson says. “Everybody has a dream of doing their own thing, but they don’t know how to get money and put all the pieces together, and this knocks one of the barriers down. I think you’ll be seeing in the next four to six months a ton of stuff from very accomplished designers trying it out as well.”