Pepe Vargas remembers how it all started. Somebody at St. Augustine College, a small school in Uptown that provides bilingual education to a mostly Hispanic student population, snagged a $20,000 grant to create two film festivals in 1985 and 1986.

Although the Hispanic Film Festival, as it was christened, featured only 14 entries the first time around, its setting's rich historical context portended good fortune: The movies were projected onto a concrete wall inside a large storage building that once housed Essanay Studios, the seminal silent-film-era studio where Charlie Chaplin, among other early film stars, made some of his first movies as the rootless tramp.

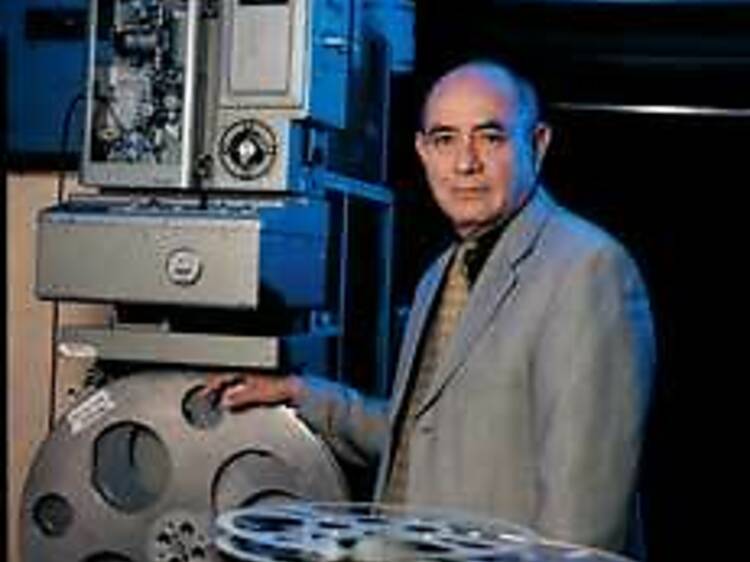

Something of a tramp himself in those days, Vargas was driving a cab, trying to figure out what to do with his up-to-then chaotic life. He had no idea that a series of miscalculations by some experts were about to launch him on a personal crusade he's been devoted to ever since: raising awareness of Latino culture as the director of the Hispanic Film Festival's immensely successful offspring, the Chicago Latino Film Festival. The 21st installment of the fest, the nation's oldest, largest and most comprehensive showcase of contemporary cinema from Latin America and Spain, begins Friday 8 and runs through April 20. (For those of you who are counting, it's 21 years old because the fest was once held twice in a single year.)

"A friend who was connected to the college asked me if I wanted to help with the film festival. They wanted to use it as a recruiting tool for the college," says Vargas, who'd just finished a degree in television and film production at Columbia College and leapt at the opportunity to serve as a consultant.

He lobbied for a program that would appeal to a broad audience by comprising English-subtitled films from several Latin American countries and Spain. His multicultural outlook came from personal experience. A native of Colombia, he'd lived in three Latin American nations: his own; Argentina, where he earned a law degree, practiced labor law, and then had to flee when the ruling military junta began arresting and killing citizens with suspected leftist leanings during that nation's Dirty War; and Mexico, which permitted him to work as a paralegal. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1979, attempting a soon-aborted career as a photographer in L.A. before "growing bored" of that city and moving to Chicago, a city he knew nothing about, save what he'd seen in gangster movies.

About 500 people showed up for the first fest, but the college failed to register a single new student. St. Augustine officials were reluctant to give it another go in 1986, Vargas says, "but they had to do it again because they had the grant money." Vargas took over as director, assumed fiscal and administrative responsibilities on behalf of the college and upped the film count to 19. More than 3,500 people showed up. The college recouped $4,000 of the $10,000 spent on the fest, but again, no one signed up for classes.

"So—I couldn't believe it—they gave it up," Vargas says, "and I thought, 'There's something here.'"

The next year, he founded an organization named Chicago Latino Cinema, convinced Columbia College (today home to the largest collegiate filmmaking program in the country) to house the fest at its Getz Theater building, charmed Cultural Affairs czar Lois Weisberg into kicking in $10,000 ("Had we not received that money," Vargas says, "we'd not be here today"), and got the city to promote it as part of Chicago's sesquicentennial celebration. Eight thousand ticket buyers proved that Vargas's intuition had been right on target.

But the fledgling festival's early success was also inadvertently ensured by the organizers of the Chicago International Film Festival (CIFF), the city's long-reigning festival kingpin and the oldest international film fest in North America. The previous September, the CIFF had turned down Mexican director Paul Leduc's 1986 Frida Kahlo biopic, Frida, Naturaleza Viva. Vargas, whose fest was scheduled for the following May, pounced.

"You know, it's not a masterpiece, but it's a good little film," says Vargas, who booked it and then watched incredulously as nearly 1,500 people attended three screenings in one day at the 500-seat 3 Penny Cinema. Vargas brought the film back in August for a one-night-only screening at the Music Box and promptly sold out two shows.

The same thing happened the following year when the CIFF rejected La Gran Fiesta, the first feature-length movie produced by the Puerto Rican film industry. "Not a masterpiece, but a good little film," repeats Vargas, who has always made a point of championing less-than-great movies in the interest of supporting underdeveloped film industries in Latin America. He snatched it up, screened it twice at a special March premiere at the 3 Penny prior to the fest, and added a 1am screening to accommodate the overflow, which extended in a line down Lincoln Avenue.

"To be honest, I'm deeply grateful to the Chicago International Film Festival for rejecting those films," he says. "It gave us a challenge, an opportunity to do things our own way. There had been efforts to create a Latino film fest as a branch of the international fest in the late '70s and early '80s, but in the end it didn't work. I've got nothing against them, but we must be doing what is ours. We can't entrust it to anyone else."

When Vargas says "we," he's speaking in global terms, referring to all of the Latinos in the world. "We value the opportunity to use the festival as a cultural tool," says Vargas, who today oversees a tiny staff in an office at Columbia College, has an 18-person board of directors, hires temporary volunteers and manages an annual festival budget that's grown to $1.2 million. Still, the festival remains, for the most part, a one-man endeavor. "The Latino family is composed of more than 20 nationalities, so we make a conscientious effort to get films from all those countries. This year, we have pretty much all countries except for Panama."

Over the past 20 years, Vargas estimates that he and his team have screened about 1,000 films viewed by more than 250,000 people. There have been plenty of unexpected highlights, such as The Girl of Your Dreams, starring a young Penelope Cruz, and Guantanamera, Tomas Gutierrez Alea's last film, made with assistance from the Cuban Film Institute—and denounced by Fidel Castro. And the festival's Gloria (as in "glory") Award, instituted six years ago to honor lifelong contributions to Latino culture, has been presented to the late Celia Cruz and Rita Moreno, among others. [This year's award will go to legendary Brazilian director Carlos Diegues, who will attend a closing-night screening of his 2004 comic parable, Deus e Brasileiro (God is Brazilian).] But the multicultural agenda trumps glamour, Vargas says.

"We're not interested in bringing stars to the festival," he says. "First, it's really costly. And then, celebrities often have special requests—no, no, no. We go for the films that need to shine."

This year, that includes such unsung curiosities as Suite Habana, a dialogue-free film from Cuba that proceeds like a musical composition as it follows the lives of ten of the city's citizens, and Caribe, the biggest blockbuster in Costa Rica's history, about a husband-wife couple who find themselves at the center of a struggle between angry locals and a multinational oil company that wants to drill off the coast.

Fortunately for Vargas, securing such films has remained relatively easy despite the emergence of other Latino film fests in San Diego, Los Angeles, Miami, Boston and New York. "We support them," Vargas says. "We're not interested in keeping Chicago as the only one. It's a necessary development if we are to change perceptions about Latino culture."

To that end, Vargas doesn't limit his entrepreneurial vision to cinema. Since 1995, he's also produced Latin dance and music concerts and other cultural events year-round, from tango shows to a 1996 appearance by the Ballet Moderno y Folklorico de Guatemala at Navy Pier. (The total annual operating budget for the non-profit organization is about $1.6 million, of which the film fest devours the lion's share.)

As this year's edition of the festival unfolds, he's about to launch a campaign to raise $50 million for the creation of the International Latino Cultural Center of Chicago, a sprawling, multicultural, multi-arts facility he wants to build in a central city location. (In 1999, Vargas also adopted the name for his organization.) Three movie theaters are planned for the center, and Latino and Spanish-language cinema would be shown throughout the year, making the Chicago Latino Film Festival, should the center one day become a reality, obsolete—though Vargas says he'd gladly host another organizer's film fest at his center.

"It would be such a waste to stick to film only," Vargas says pointedly. "Films have such a power, but they're not the only thing. How about poetry? Plays? Dance? We'll have a majestic place, and it'll be an open invitation for people to come in and enrich their lives at a poetry reading or just have coffee or a meal. Yes, it's a comprehensive, ambitious and risky proposition, but soon Latinos will number 1 billion people from all these countries, so we cannot just be the Chicago Latino Film Festival anymore."

Vargas admits that this time he is reaching for the stars. When he told Mayor Richard Daley the project's price tag at a meeting set up by a still-supportive Weisberg, Vargas says the mayor's eyes grew wide and he responded, "You want another Art Institute?" "I said, 'Precisely.'"

"It will be costly. It's not going to come to us on a silver platter," adds Vargas, pinning some of the difficulty of winning the city's backing on the $475 million spent on Millennium Park, which has made the city and corporate benefactors hesitant to invest heavily in another major cultural attraction so soon after the park's opening last summer. "We have to work hard to build credibility and create trust, and to make the festival better every year so that they look at us and say, 'Yes, these people can do it,' and taxpayers won't be opposed to the city or state donating a piece of land."

Asked if another such center already exists in the U.S., Vargas, who has always kept a low profile and refrained from bully-pulpit tactics, responds diplomatically: "Albuquerque has one, but it's very small," he says. "And Albuquerque is not Chicago."

The Chicago Latino Film Festival runs Friday 8 to April 20. For a schedule of screenings and information on how to get tickets, go to www.latinoculturalcenter.org/Filmfest.