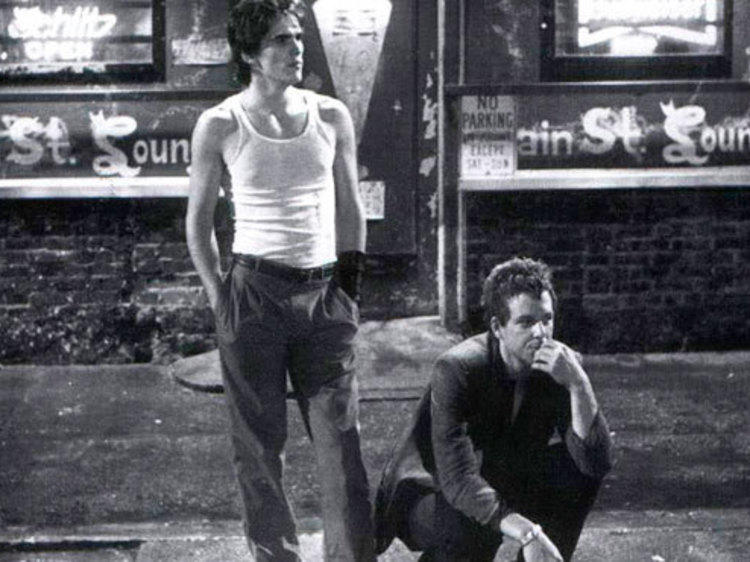

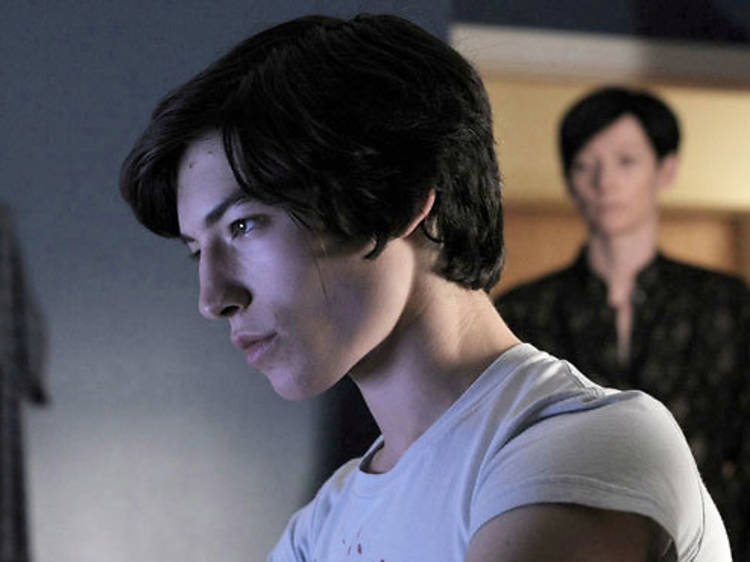

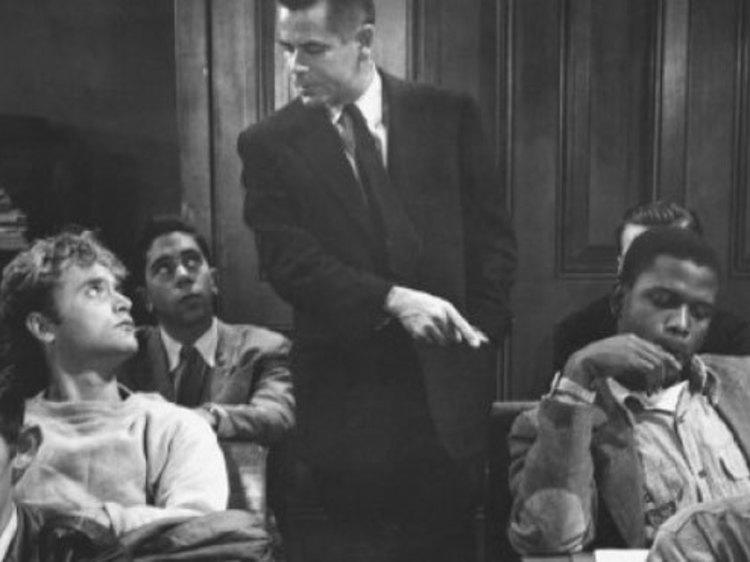

If we’re being honest, not all the kids are all right. In fact, some are downright rude. Murderous, even. Yes, to be young is to feel the weight of society’s expectations on your shoulders, but the young people on our list of cinema’s most memorable depictions of youth in revolt aren’t just your average angsty adolescents. To be frank, many of them are irredeemable assholes. But that doesn’t mean we can’t catch a vicarious thrill from watching their exploits, and recall the days when we ourselves were young, dumb and angry at the world, rather than old, tired and resigned. We’ve ranked these movies as a countdown of bad behaviour, from mildly obnoxious to the straight-up criminal. Our only parameter: they must be teens and younger, not twentysomethings.

Recommended:

🧒 The 100 best teen movies of all-time

😍 The best teen romance movies of all-time

🤯 The most controversial movies of all-time

😬 The best thriller movies of all-time