Updated for 2026: Welcome to the canon, Uncut Gems! It took a few years to allow the then-united Safdie brothers’ high-stress rollercoaster to truly sink in, but once we stopped hyperventilating, it became clear that it’s one of the all-time great thrillers, even if ‘thriller’ seems, in its case, too weak a word. Will Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme eventually join it? Time will tell.

What makes a great thriller? Well, let’s see. Are your palms sweaty? Your teeth clenched? Is your heart pumping and your leg shaking uncontrollably? If so, the chances are that the movie you’re watching is doing its job. When done right, a thriller provokes a physical response more than any other genre, bar horror. Exactly how it initiates those reactions, however, varies greatly.

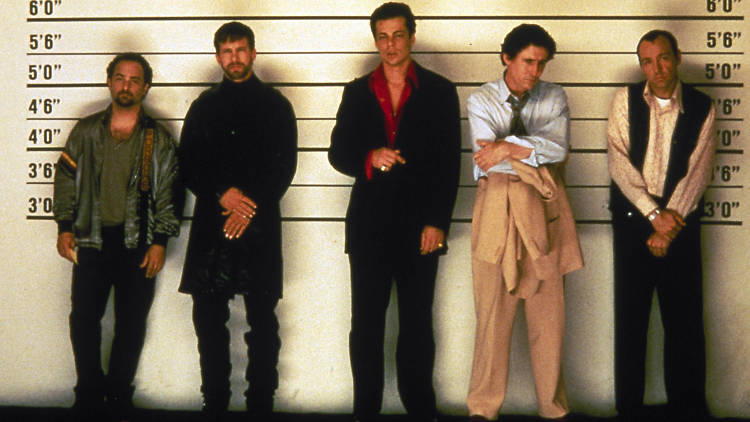

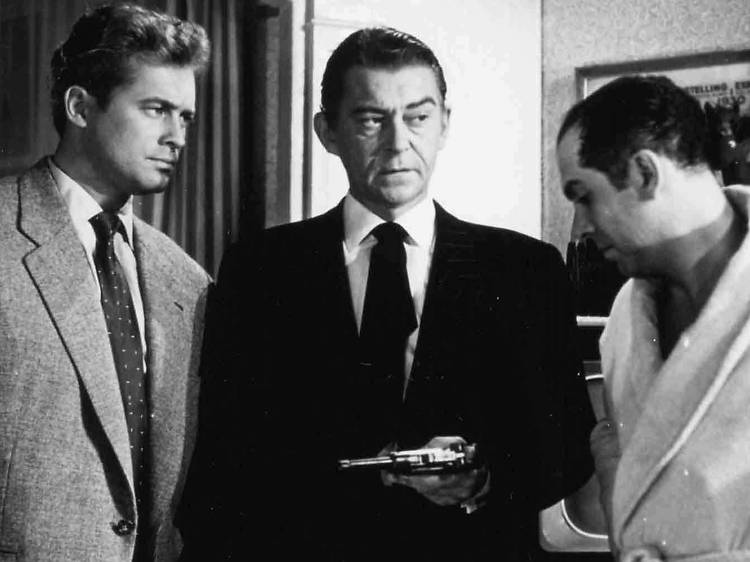

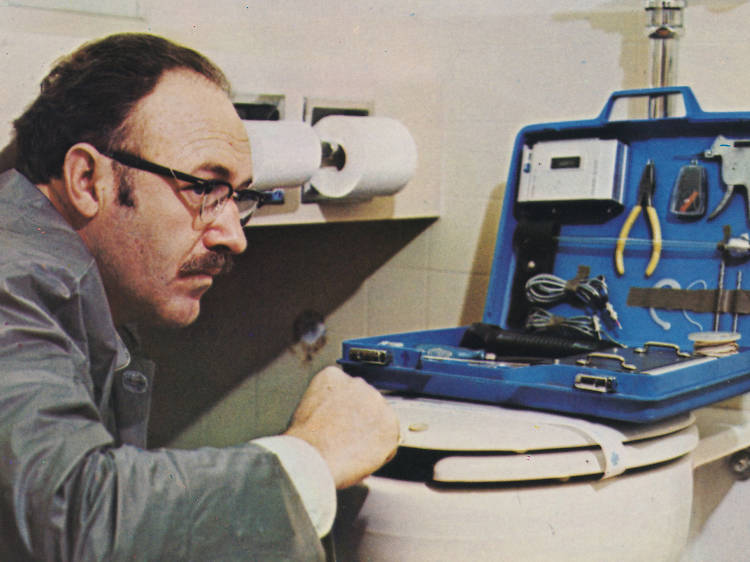

In the pantheon of the best thrillers ever made, you’ll find murder, political intrigue, espionage, conspiracy, manipulation, gaslighting, and, of course, lots and lots of crime. But as a category of movie, the thriller is also loosely defined – within the genre, you’ll find examples of science fiction, horror, heists, action, even comedy, along with the ever-nebulous ‘psychological thriller’ subdivision. In other words, the thriller contains multitudes. But the best of them will always draw you in, make you sweat and leave you breathless. Here are the 100 greatest thrillers ever made.

Written by Abbey Bender, Joshua Rothkopf, Yu An Su, Phil de Semlyen, Tom Huddleston, Andy Kryza, Tomris Laffly & Matthew Singer

RECOMMENDED:

🕯️ The 35 steamiest erotic thrillers ever made

😬 The best thriller movies on Netflix

💰 The 60 most nerve-racking heist movies ever

🧠 The greatest psychological thrillers ever made