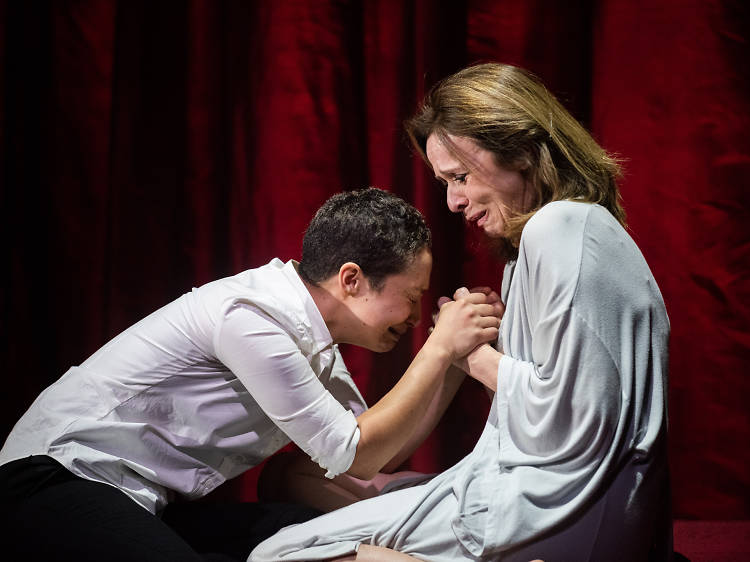

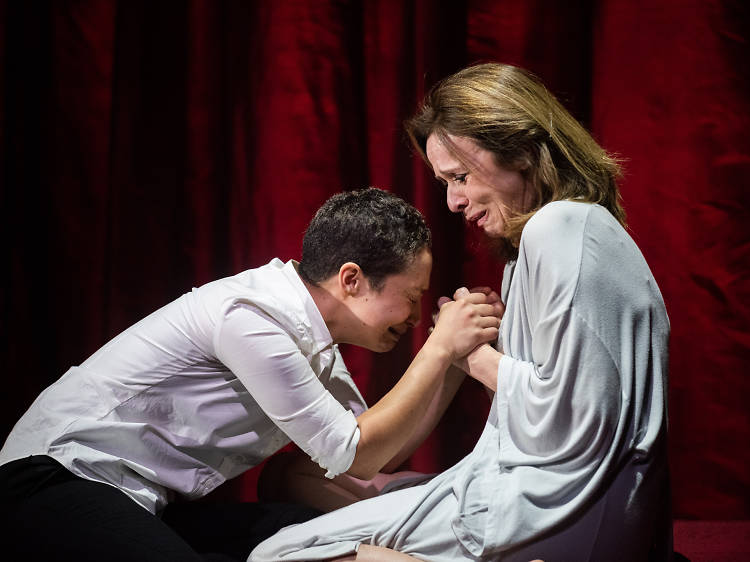

Suicide Forest

Theater review by Naveen Kumar

A craggy wooded area at the base of Japan’s Mount Fuji, the so-called Suicide Forest is a popular destination for people in pursuit of death. It is described, in the first scene of Haruna Lee’s play, as treacherous and enveloping: a quicksand nightmare haunted by lost souls. The same might be said of Lee’s perverse and electrifying psychodrama, in which the playwright performs a central role. It’s a raw, provocative and eviscerating exploration of the artist’s own identity, wrapped in the bubble-gum-pink and pastel hues of Tokyo export Hello Kitty.

Hyperfemininity and the infantilization of young women are at the heart of Lee’s inquiry, which plays out as a series of brief sketches anchored in the psychosexual imagination. A salaryman (Eddy Toru Ohno), whom Lee’s script describes as “the face of Japanese masculinity” and “a man of uniformity,” is sitting in his office when his secretary (Yuki Kawahisa)—a cartoon coquette come to life—enters on routine matters. “What are you thinking in that disgusting, perverted little brain of yours?” she demands. (Naughty thoughts, it turns out.) His daughters (Dawn Akemi Saito and Ako), dolled up as Harajuku teens, come next, circling him and giggling for money. Their school-uniformed friend (Lee) seems more doll than human; when they leave her alone with their father, she slumps limply in a loveseat.

Director Aya Ogawa’s surreal and hypnotic production, seen last year at the Bushwick Starr, handles acts of s