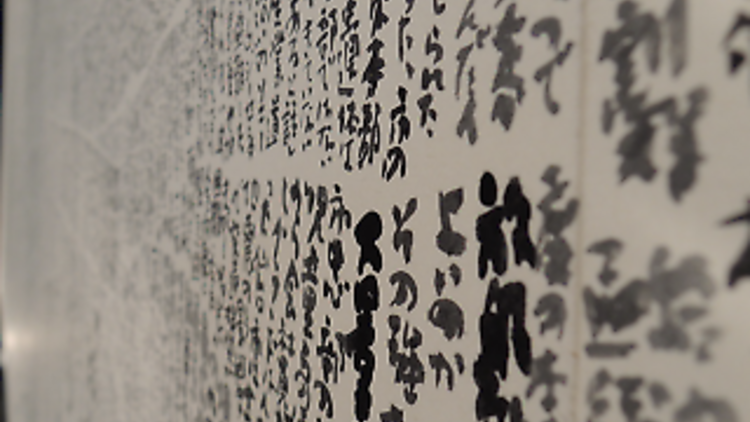

Art in Japan often comes from a philosophical standpoint, where the process is equally important as the result. This is particularly true when it comes to the Japanese calligraphy art of shodo. On the surface, this Eastern form of high art is revered for its striking characters and ideograms made with sweeping brush strokes. However, its beauty lies not just in its composition but also in its ability to capture the artist’s state of mind.

Calligraphy is part of everyday life in Japan. People learn how to write beautifully in their early childhood, and some even take extra courses. For professional calligraphers, it is more than just writing with a bamboo brush and sumi-ink; it is a life-long commitment.

As an art form, calligraphy demands not only physical but mental preparation. The paper gives you only one chance. There is no room for correction as soon as the ink touches the paper; the slightest hesitation risks ruining the work. The angle at which the brush is held, and the pressure and speed with which one applies the first stroke, define the shape of the character. The subtle variations in the thickness of and between the lines are said to be reflections of the artist’s state of mind. This approach to art is influenced by Zen Buddhism as it captures the spirit of the calligrapher in that moment in time.

The main principle of the composition is balance, for which the interplay between the black line and white space is essential. As the artist moves the brush through the white paper, the lines must have fluidity, depth and strength. Rather than writing a letter, the brush strokes draw the space. The space, in turn, defines the form. If both line and space are in balance, this aesthetic principle has been achieved. This act becomes a performance, where the artist engages with body and mind.

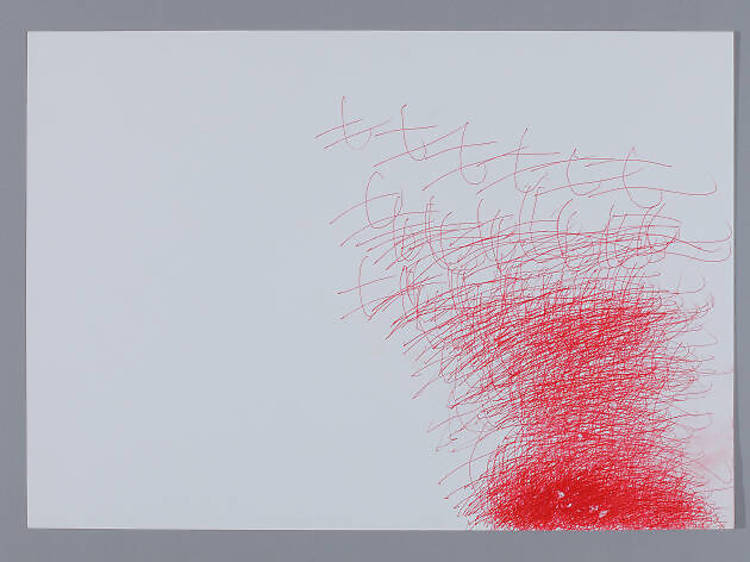

Japanese artist Aoi Yamaguchi began learning calligraphy at the age of six under the tutelage of Zuiho Sato, a traditional calligraphy master. Yamaguchi’s training involved not only perfecting her own calligraphic skill by imitating the techniques of the great masters of the past, but also studying their works in order to reflecton their spirit and philosophy.

As Yamaguchi says, ‘It is a challenge for anyone to embody their spirit in handwritten words. Meditate, prepare the ink, focus on the moment, pick up the brush and write the steady strokes in a smooth, continuous flow without hesitation. Your body and mind have to be aligned. You will make lots of discoveries about yourself, and will go through moments of struggle and self-fulfilment.’