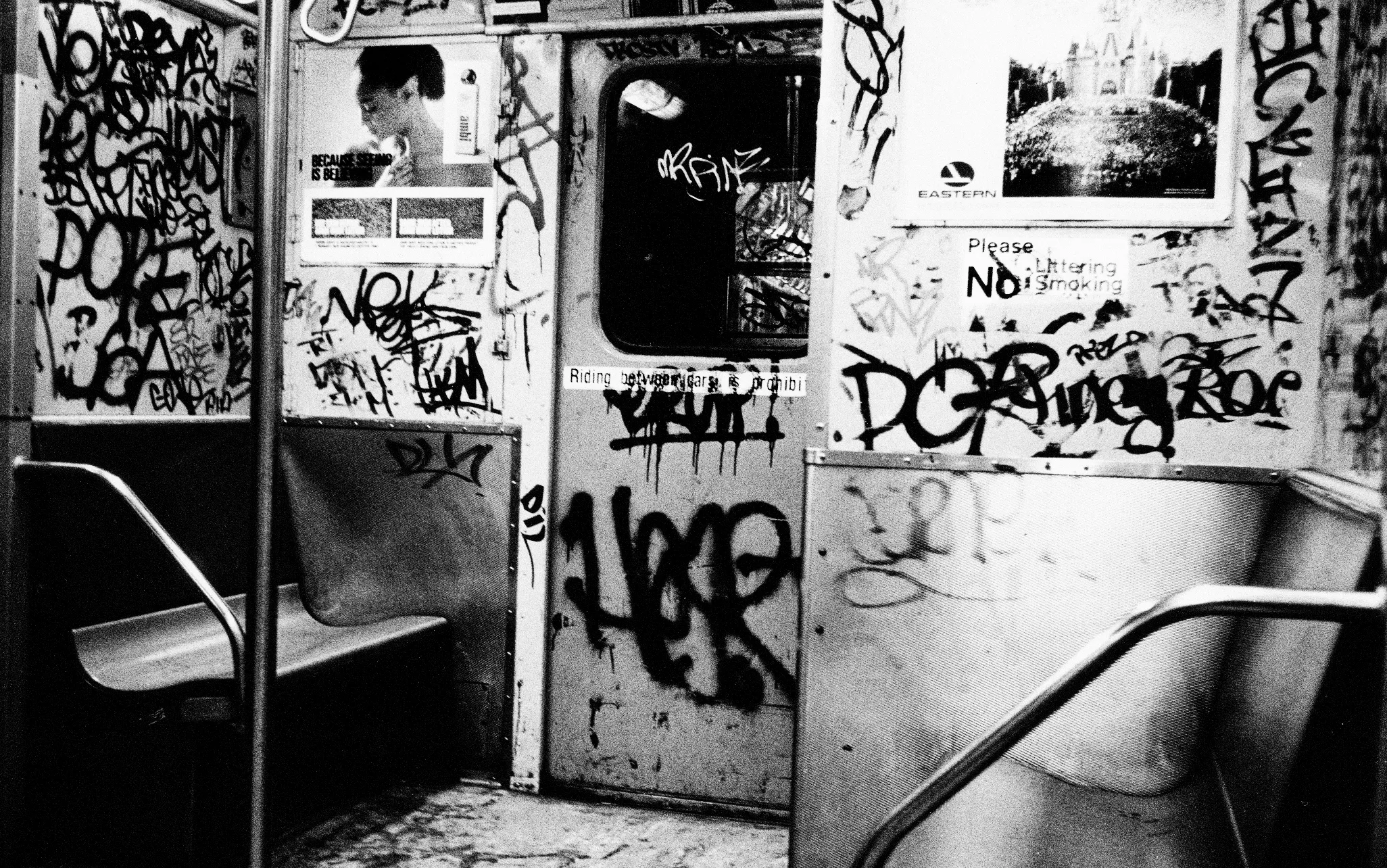

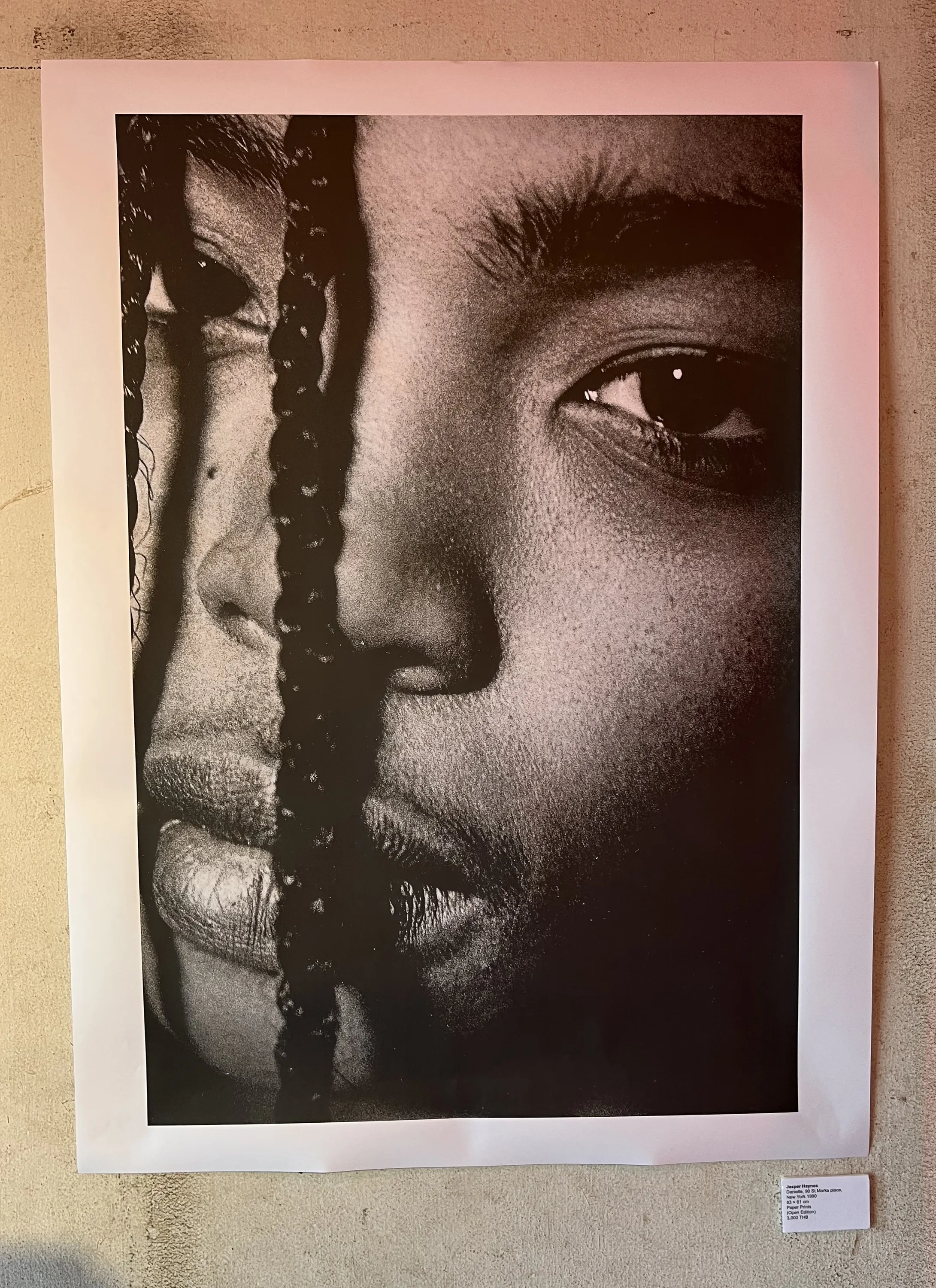

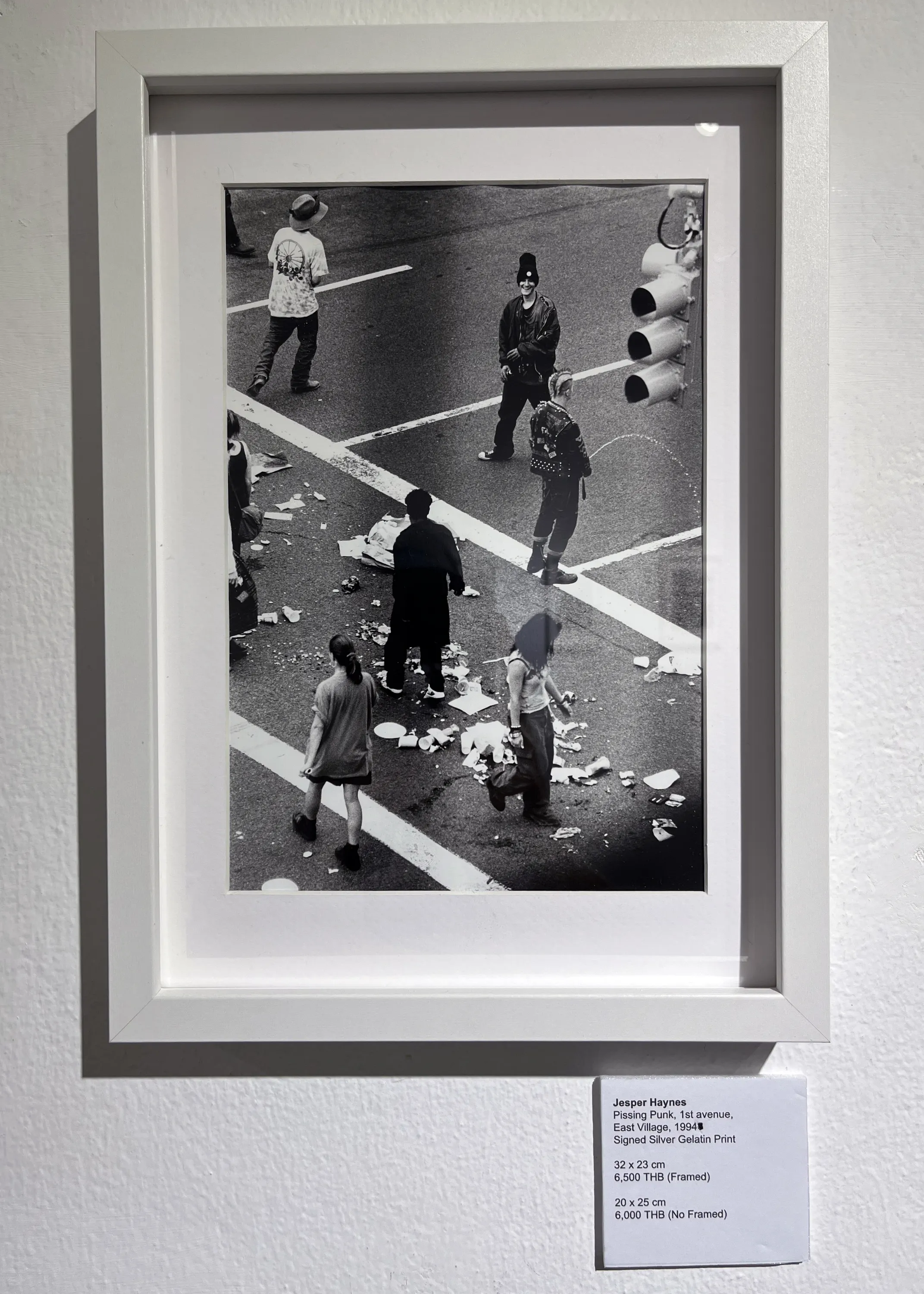

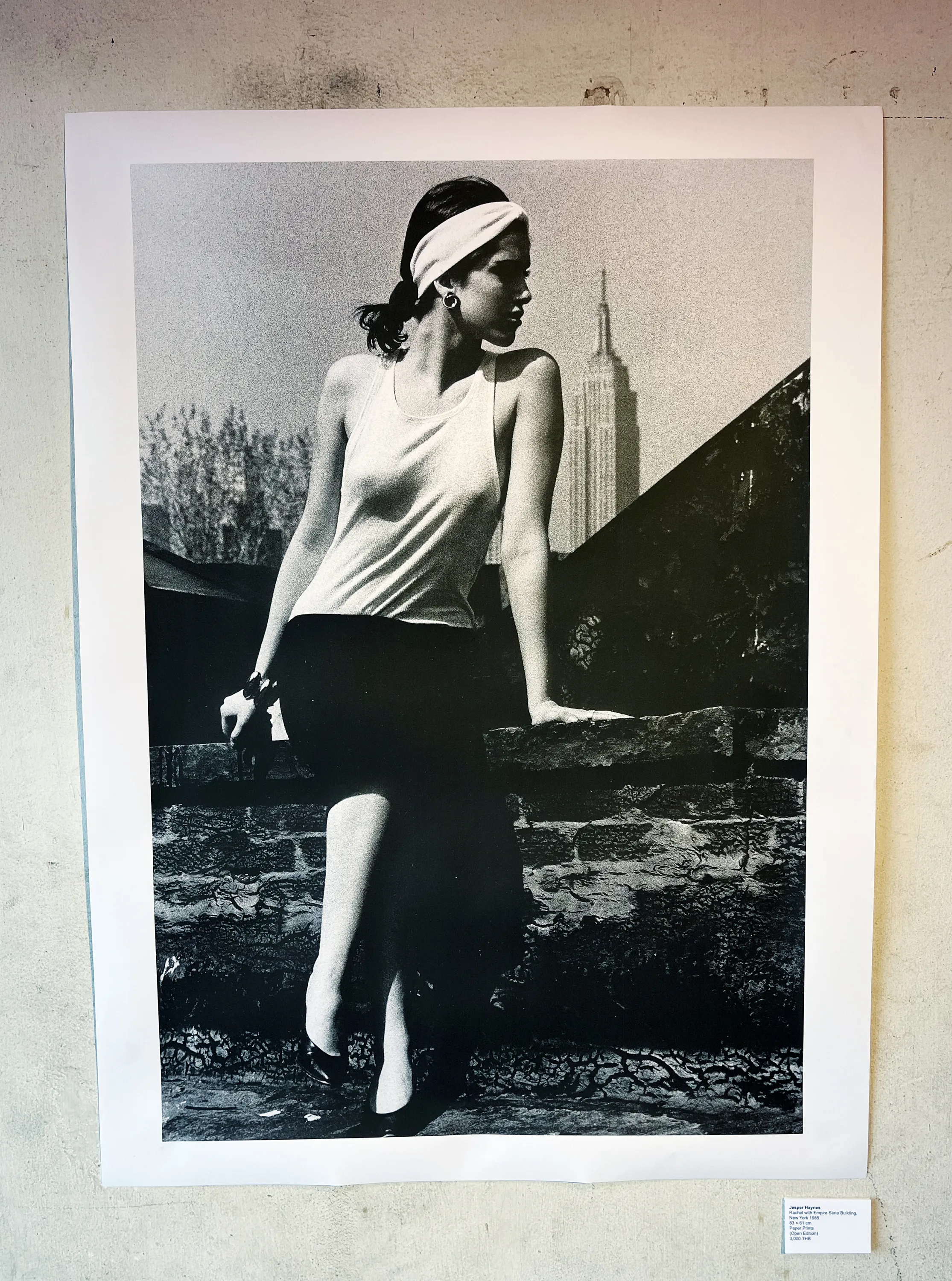

New York has been photographed to death. Every alley mythologised, every night flattened into attitude. What Jesper Haynes offers instead is something quieter and more unsettling: a record of being there without rehearsing what it might later become. New York Darkroom, his recent exhibition in Bangkok, looks back at downtown New York in the late ’80s and ’90s without soft focus or hero worship. Faces are close. Streets feel narrow. Nothing performs for the camera.

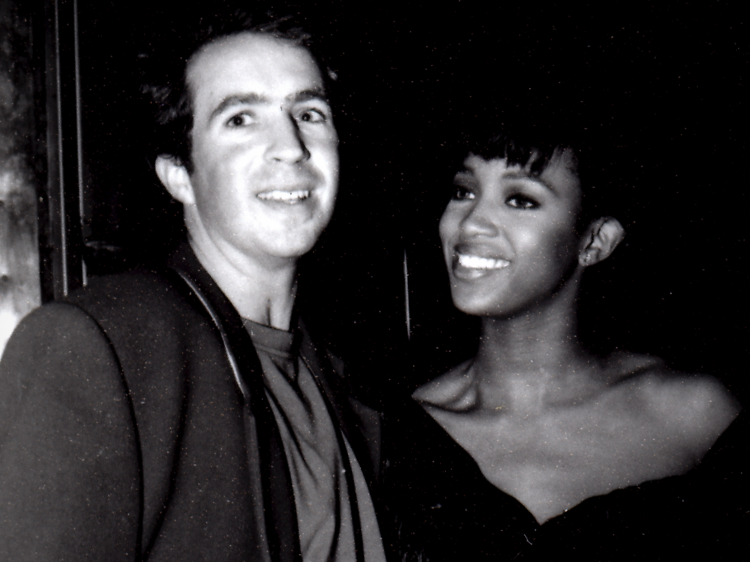

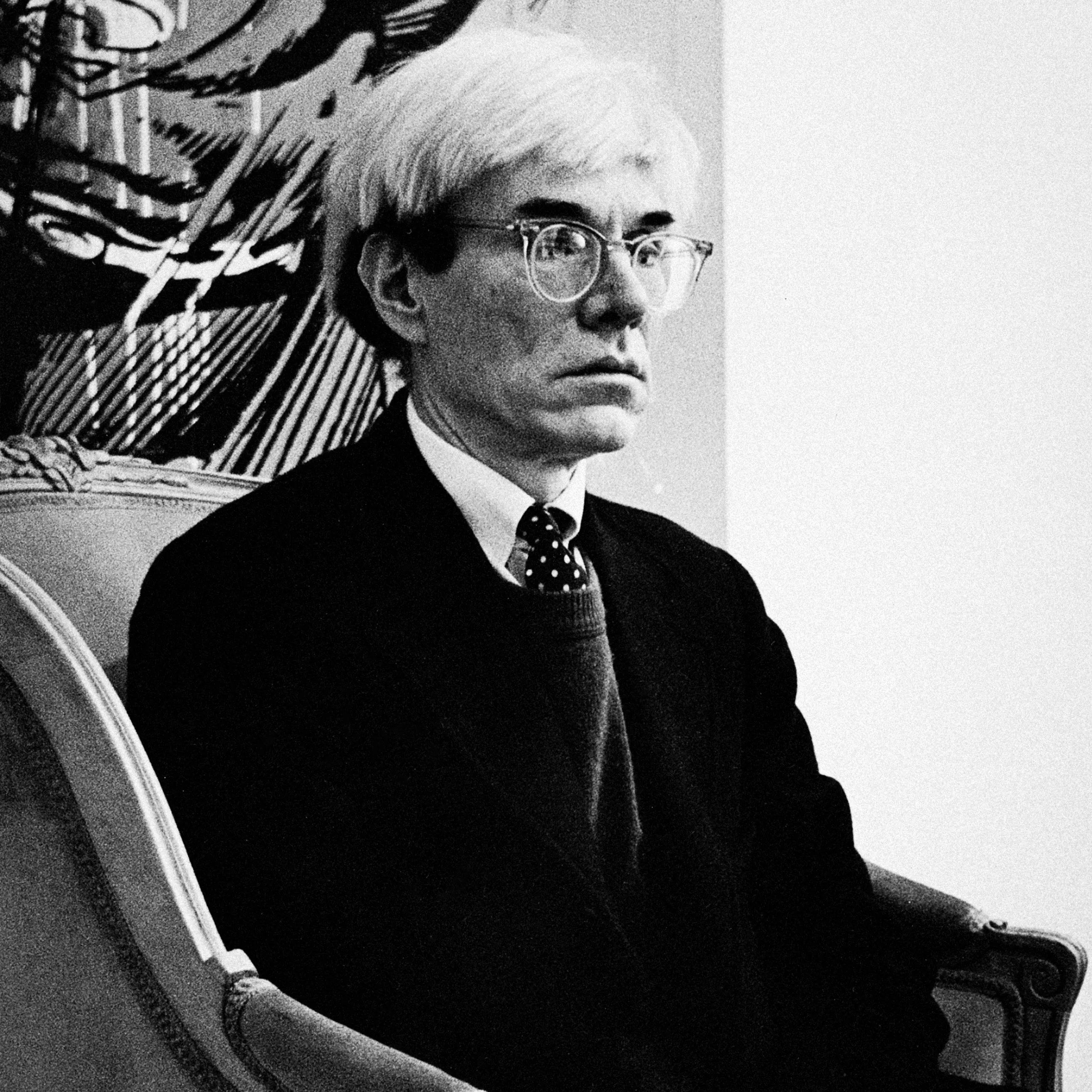

Speaking to Haynes, what becomes clear is that this work is not about legacy. It is about attention. About what happens when you show up night after night, shoot one frame instead of ten and trust that whatever remains will explain itself later. His photographs, featuring figures such as Andy Warhol, Willem Dafoe and John Lurie alongside friends, lovers and strangers, feel less like cultural artefacts than private evidence. Proof that something happened. Proof that he was there.

This is not nostalgia. It is memory with its elbows out.

Before New York became a story

When I ask Haynes whether the New York he photographed felt historic at the time, he doesn’t pause. ‘Simply immediate,’ he says. No sense of witnessing a future legend. No awareness of living inside a reference point. Just now.

That matters. The photographs in New York Darkroom don’t announce themselves as documents of an era. They are too absorbed in the moment for that. Haynes arrived in New York as a teenager after Andy Warhol invited him to visit, an invitation that quietly rerouted his life. He wasn’t chasing success or stability. ‘I wasn’t interested in the American Dream,’ he tells me.

“I was fascinated by the idea of artists all coming to one city.”

What he found was a city on the brink and on the cheap. Bankrupt, rough around the edges and somehow generous because of it. ‘Rents were very cheap. I paid about $150 a month,’ he says, still sounding faintly surprised by his own memory. Everyone around him was making something. Writers, filmmakers, singers, dancers, DJs. Not networking. Just surviving together.

That sense of shared urgency runs through the work. New York isn’t framed as glamorous or dangerous or romantic. It simply exists, pressing close to whoever is willing to stay out late enough.

One roll, one night, one frame

Haynes shot constantly. Often at least a roll of film a day. Not out of obsession with productivity, but because that was the rhythm of his life. He went out seven nights a week for years. Nightclubs, apartments, dinners that blurred into mornings. What anchored it all was the darkroom.

“The beautiful thing about being in the darkroom after being in a nightclub all night was that I was alone.”

‘It was a form of meditation.’ The isolation mattered. Developing film became a counterweight to the noise, a private space where nothing demanded explanation.

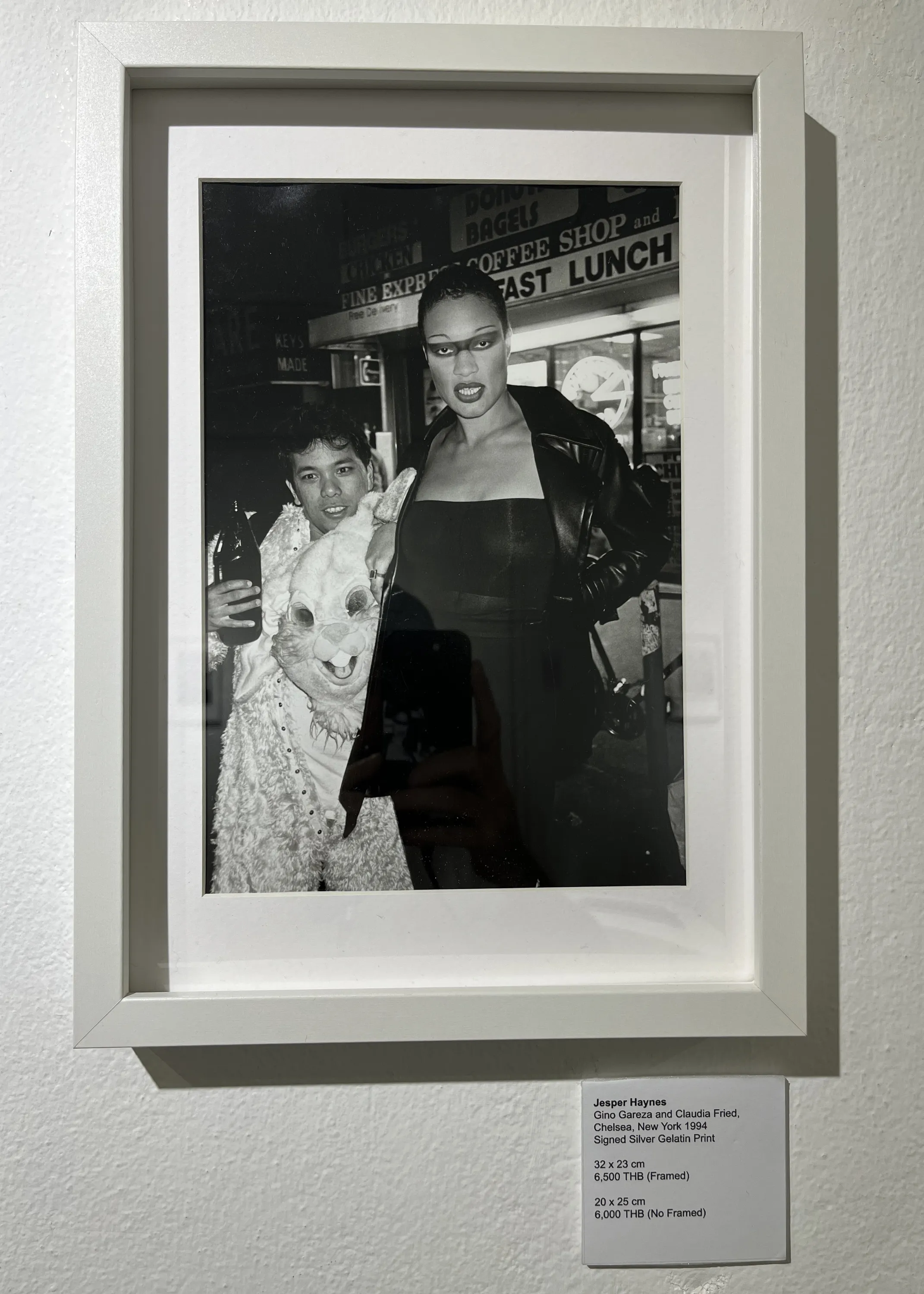

This is why New York Darkroom insists on showing contact sheets. Haynes wants the process visible. Not to demystify it, but to make it human. Hesitation. Repetition. Uncertainty. ‘I want it to be immersive. I want people to connect and experience it,’ he says.

What strikes me most is how often there is only one frame. One click. No backup. ‘That’s how we were shooting back then,’ he explains. You paid attention. ‘You had 36 pictures. You couldn’t waste them.’

We talk briefly about the return of film photography and whether it means anything. Haynes shrugs at trend language. Film forces intention. It slows the hand and sharpens the eye. ‘When I shoot with film, I’m much more conscious,’ he says. Where light lands. Where your eye goes. Digital allows for correction later. Film demands decision now.

Trust, ethics and knowing when to stop

The intimacy in Haynes’ photographs feels earned rather than taken. That is not accidental. ‘It’s about gaining trust and being honest,’ he says. ‘I don’t like to sneak pictures.’ He draws a clear line around vulnerability.

In the late ’80s and ’90s, a camera still carried a certain innocence. ‘People were happy to have their picture taken,’ he says. Now, suspicion arrives first. Everyone is already performing for a future audience. That shift has changed not only photography, but responsibility.

Haynes was conscious of ethics even then. Some nights were messy. Alcohol blurred edges. The real decision came the next day. ‘I’d have to ask myself whether it was okay to show those pictures,’ he says. ‘I don’t appreciate photography that takes advantage of people.’

Time has sharpened that instinct. He shows far less nudity now, not because he has become cautious, but because he feels accountable. ‘They were 20. They weren’t thinking about their picture being shown in the future,’ he says. Sometimes he contacts people he hasn’t spoken to in decades to ask permission. In a world reshaped by AI and endless reproduction, that care feels quietly radical.

Listening to him, I realise how rare it is to hear a photographer speak about restraint without self-congratulation. This isn’t a moral pose. It’s simply how he works.

Three photographs, three small universes

New York Darkroom includes well-known figures, but fame is never the subject. Context is. Three images make that especially clear.

The first is a horizontal portrait of Andy Warhol, taken in Stockholm. Haynes was still in high school. A friend tipped him off that Warhol would be at a private home for a TV interview. He skipped school, grabbed books and photographs and biked over. Somehow, he slipped inside.

For an hour, it was just the two of them, waiting while lights were set up. Warhol was calm, curious, slightly shy. ‘He was asking me more questions than I asked him,’ Haynes remembers. The photograph was taken with a Minox, the same camera Warhol used. One frame. No before or after. ‘I thought, okay, I have it. I don’t need to take two.’

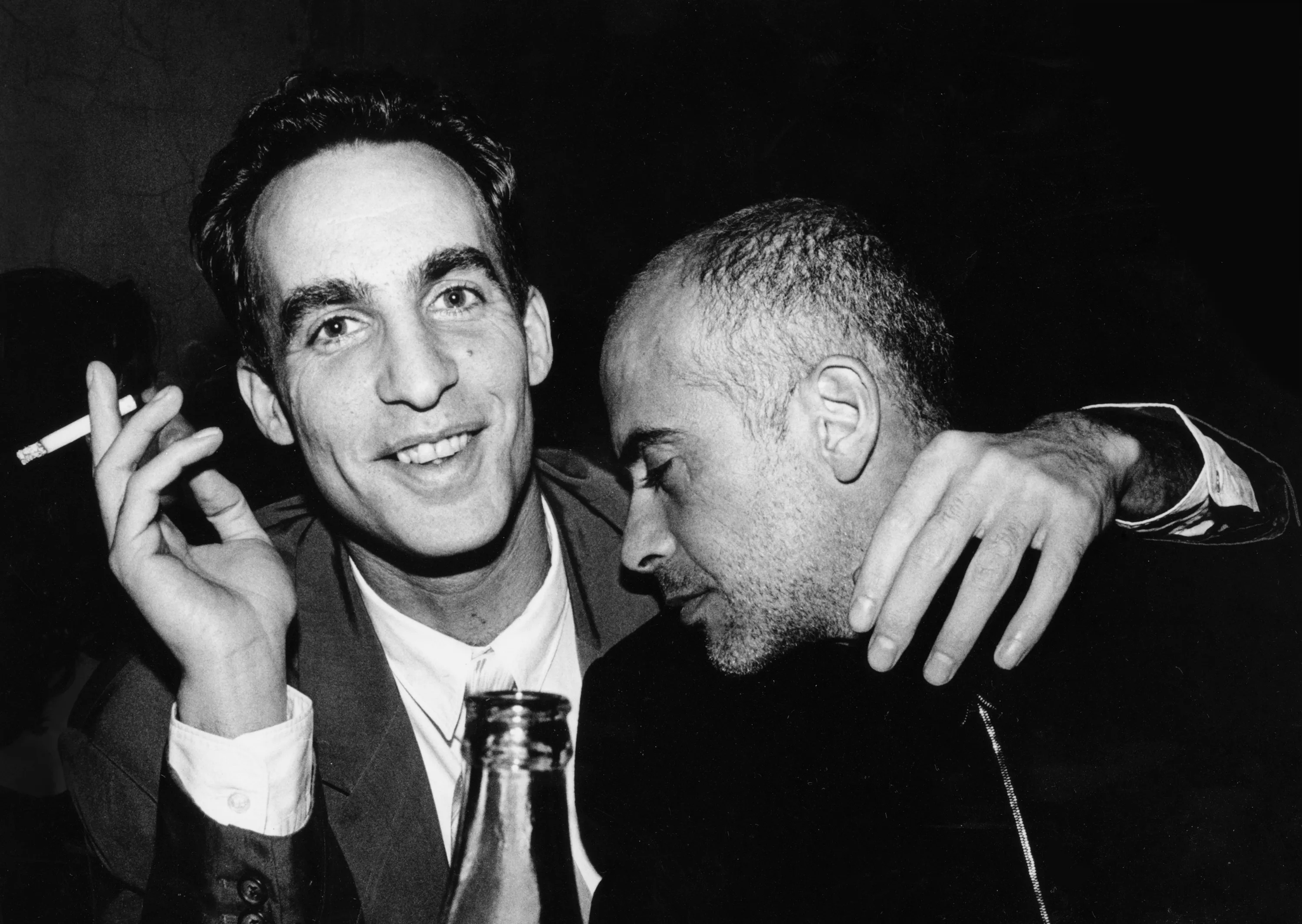

The second image shows John Lurie and Francesco Clemente at Club MK’s in 1989. It was a dinner party. Haynes already knew Lurie through friends. He photographed them the same way he photographed everyone else that night. ‘It wasn’t a moment of “oh, there’s John Lurie”,’ he says. Keith Haring appears in another frame. Someone unknown in the next. Fame dissolves into proximity. The ease comes from trust.

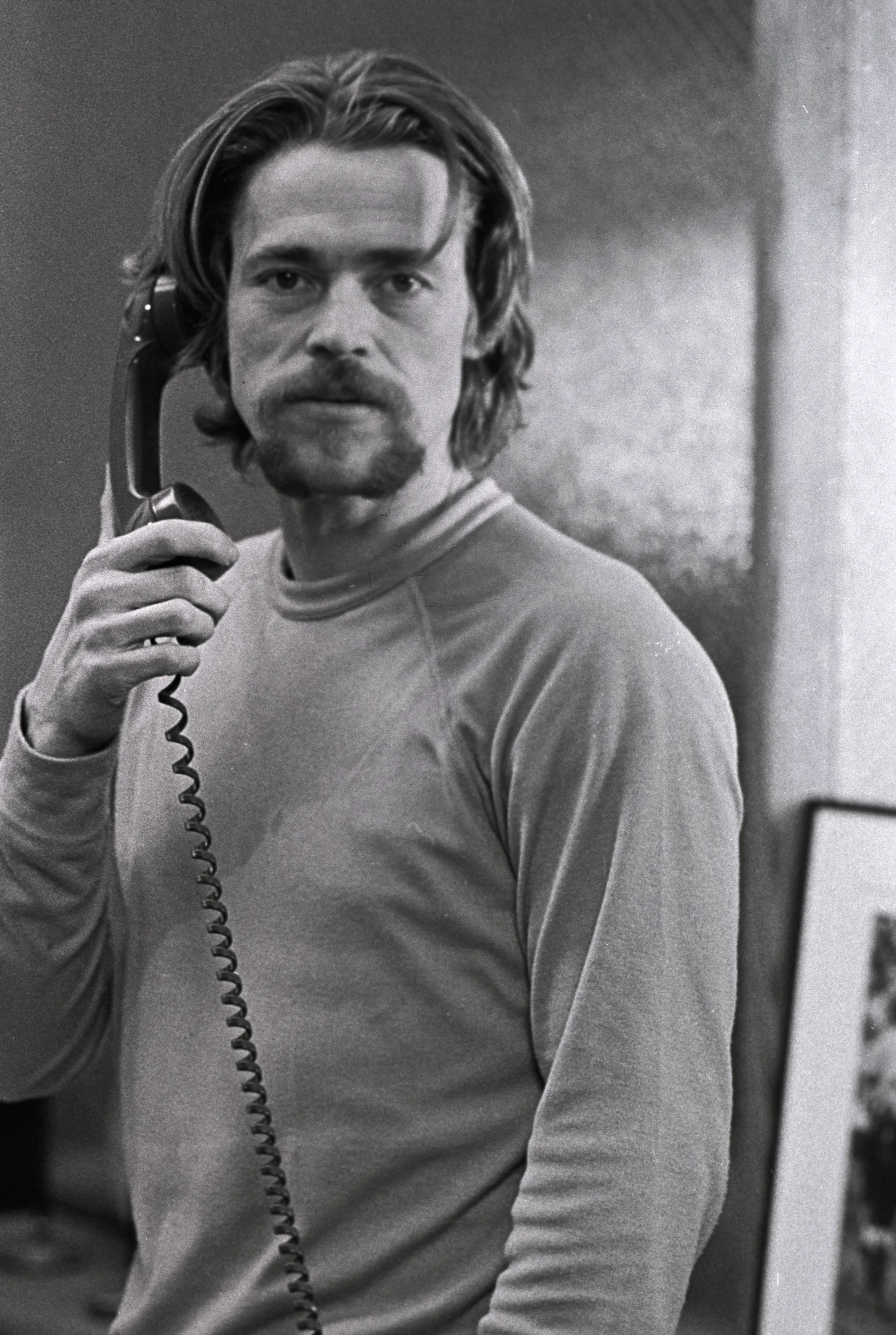

The third photograph captures Willem Dafoe mid-phone call in New York, also in 1989. Haynes knew him through a friend in the same theatre company. There was no direction. No interruption. ‘He knew I was walking around taking pictures,’ Haynes says. One frame. That was enough.

Bangkok, distance and what still feels alive

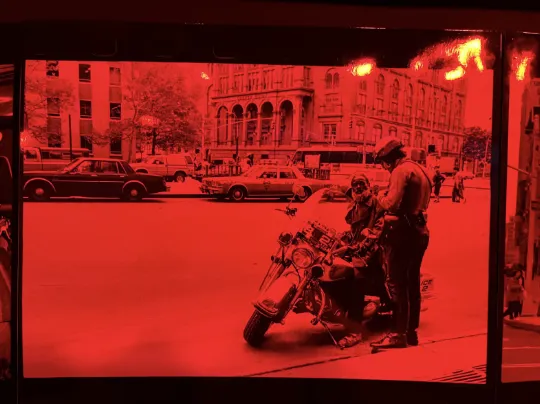

Showing New York Darkroom in Bangkok feels less like a detour and more like a continuation. Haynes has been coming here since 1987. ‘I love Bangkok,’ he says. Not despite its roughness, but because of it. ’

Texture is a word he returns to often. Old buildings beside new ones. Main roads giving way to narrow sois. ‘You feel like you’re in the middle of the city,’ he says. For a photographer, that friction matters. He talks openly about wanting to make a book about Bangkok one day. This is not a passing fascination.

Distance has changed how he sees New York. After 40 years, it no longer surprises him. Image saturation has flattened everything. Instagram. Advertising. Endless visual noise. ‘There’s a point where you feel almost like you’re going to throw up,’ he says, half amused, half exhausted.

What still cuts through is personal work. ‘The more personal it is, the more interesting.’ That belief underpins New York Darkroom. It is not trying to capture everything. It is trying to understand something.

Community, he says, was the biggest lesson New York taught him. Not the clubs, despite how often he was there, but home. An East Village apartment with a constant flow of people. Dinner parties several times a week. The buzzer ringing endlessly for 20 years. That life became the subject of his book St Marks 1986–2006, which he considers his most honest work. ‘That’s inside,’ he says. New York Darkroom is the outside view.

Photography, for Haynes, is both preservation and self-understanding. A way of seeing how he became who he is.

“If I hadn’t taken the pictures, I would have totally forgotten.”

As if those lives might have slipped out of existence altogether. New York Darkroom does not argue for a better past. It doesn’t pretend things were purer or freer. It simply shows what it meant to look closely when fewer people were watching themselves. In an era obsessed with speed and visibility, that quiet attention feels almost confrontational.

If you want to experience a city not as a myth, but as a series of shared nights and small decisions, this is an exhibition worth spending time with.

Catch New York Darkroom at Chaloem La Art House from January 24 to February 14, midday to 6pm.