Like your culture raw and sensual? Bangkok’s first world-class art collection, Dib Bangkok, has just opened. While biennales have brought brief glimpses of works by top foreign artists, we at last have a destination art museum.

The late art aficionado Petch Osathanugrah had collected over a thousand major works by prominent artists. Their showcase occupies a quiet soi between the glitz of Ekamai and the grunge of Khlong Toey. After Petch died unexpectedly, his son Purat ‘Chang’ Osathanugrah completed the project with his father’s chosen architect and director. The result is spectacular.

It all looks very sleek, but Dib actually means ‘raw.’ The museum’s mission seeks ‘raw authenticity.’ Its inaugural exhibition ‘(In)visible Presence’ is all about drama, texture and sparking raw response. The 81 works by 40 artists stimulate the senses, whether aromatic herbs, kinetic sculpture, sound art, spaces coloured by the weather or art you can sit on.

‘(In)visible Presence’ also pays tribute to Petch, an impish character who used to be a pop star. Overseeing Dib from a ledge in the cafe, his startling portrait ‘statue’ is a plastic doll likeness playing guitar ‘in the raw.’

Dib literally opens with a bang. A baseball bat lies chained to a long white wall lining the entrance. The Australian Marco Fusinato called it ‘Constellations’ due to the shattering marks made when visitors smash that bat into the pristine plaster. It’s cathartic to whack out your stress on an artwork, but there’s a surprise. Sensors in the wall amplify your bang to 120 decibels. It’s more than a vibe – everything vibrates.

Raw applies to the architecture too. Adapted from a warehouse, it features distressed columns and an original Sino-Thai grille. ‘We all carry scars and marks from our life story,’ says museum director, Miwako Tezuka, formerly of New York’s Japan Society and Asia Society. ‘Consider Dib as a living creature that will grow with us. So we will always be unfinished, uncooked, because we are evolving.’

The building is an exhibit in itself. Playfully geometric, it was conceived by WHY Architecture. Founded in 2004 by a Thai, Kulapat Yantrasast, WHY has sculpted cultural centres for A-list clients including MOMA, Harvard, the Louvre, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Gallery design is a way for cities to brand and Dib could become a signature of Bangkok, which lacks statement landmarks due to a supposed ban on foreign ‘stararchitects.’

‘The warehouse came from the 1980s, however, it has been converted with a truly modern aesthetic, incorporating industrial history,’ Miwako adds. ‘However, once you’re inside you never feel suffocated. It is always human scale. There’s always human touch.’ Some art you can indeed touch, but most you shouldn’t, and docents are on hand to instil art etiquette.

Upon arrival, you’re hit by the sheer scale. The structure’s also conceived as a backdrop for selfies right from the gate. Cars dip to park beneath a reflecting pool that mirrors the saw-tooth skylights and the bevelled conical tower known as the chapel, which houses enormous eggs pressed from household utensils by Indian artist Subhod Gupta.

You emerge into a courtyard flanked by the galleries, event halls and Watthu-Dib Bistro & Bar, where the former chef from Shades of Retro focuses on natural flavours. Across the courtyard, gigantic stone spheres by Alicja Kwade resemble planets. “She often uses chance to determine her work,” explains curator Ariana Chaivaranon. “She would play with marbles, and this random movement ends up determining the placement.” They’re so heavy the floor had to be reinforced. Quarried from around the globe, each orb of stardust feels cooler or warmer, rougher or smoother, spangled or marbled. “We’re also playing with scale, so are these tiny worlds, or a giant’s marble set that shrinks us?”

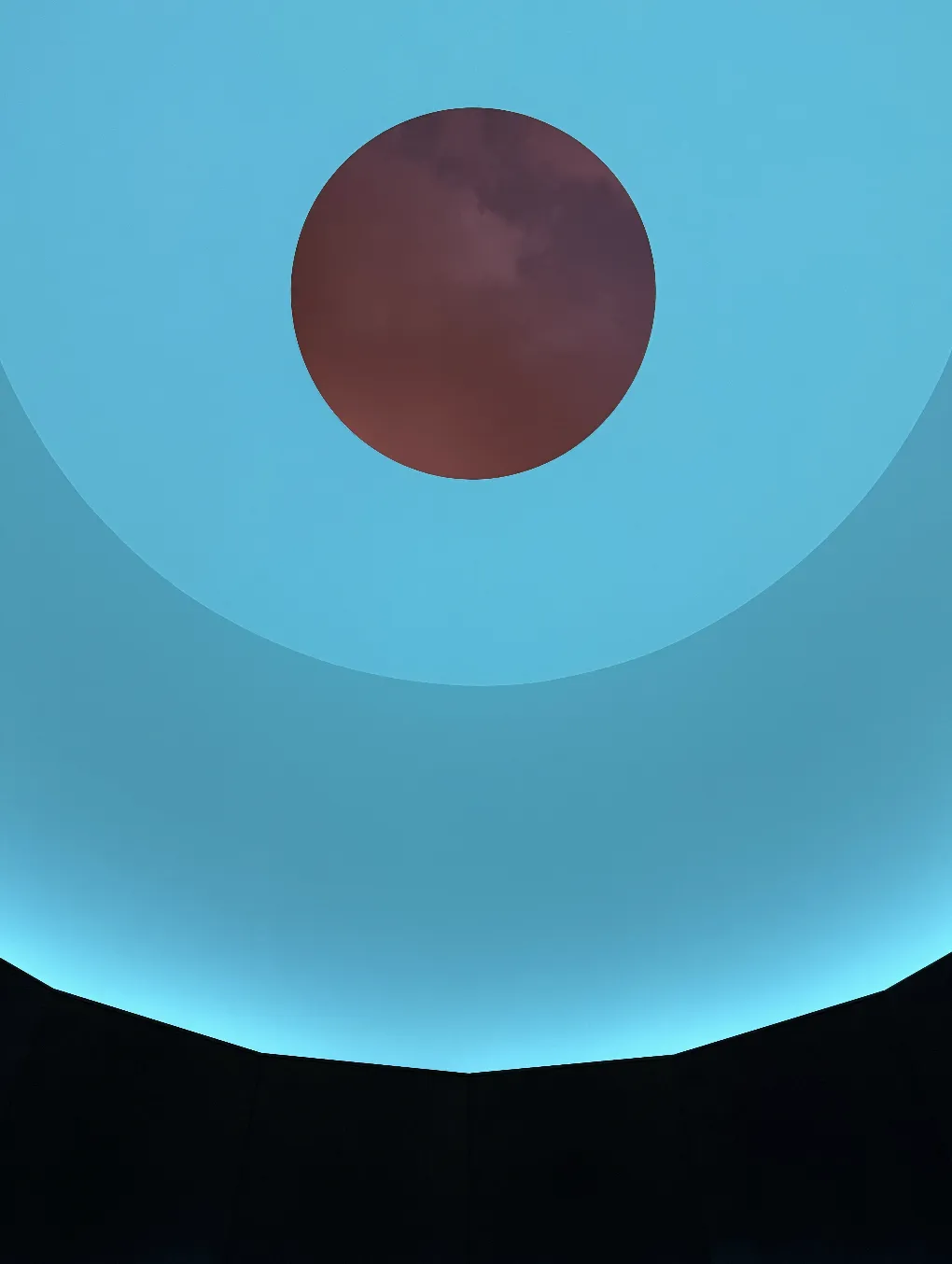

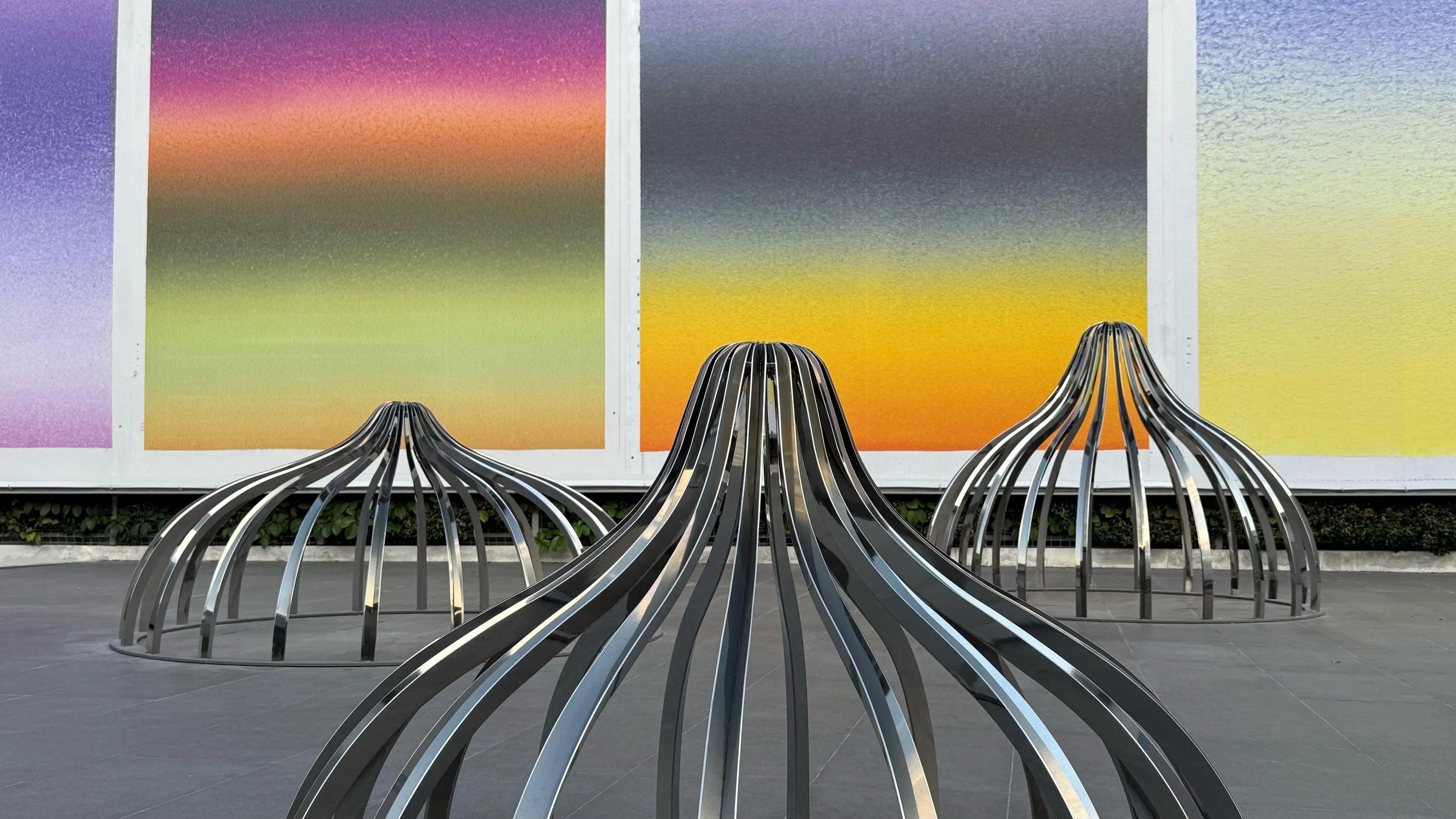

From the elevated terrace dotted with metal breast stupas by Pinnaree Sanpitak, towers another architectural artwork. ‘Straight Up’ by American James Turrell features one of his famous cameras obscura. A room below holds its projection, while a room atop its staircase frames the sky, with sunset requiring an extra ticket.

The gigantism continues inside. Daylight suffuses vast white halls in the ground and top floor galleries. Floating in the ground floor, a foil dirigible by Korean star Lee Bul gets inflated daily. That lightness contrasts with the weight of Jannis Kounellis’s steel bed fixed to a reinforced wall. With cloth rolls pressed between girders, it makes everyday life monumental.

Dib’s great service is to show Thais ranking alongside top world artists. Surasi Kosolwong has shown in Tate Modern, yet hardly ever at home. Here you can sit in his suspended upturned VW Beetle, amid mementos from his childhood holidays. More poignant is a work by Takerng ‘Be’ Pattanopas, who died suddenly this Christmas. Peering into a hole in his corroded metal shield reveals an organic realm within, inspired by Be’s meditations on mortal biology, Buddhism and the universe.

The top floor is dedicated to Montien Boonma, the father of Thai contemporary art. The works span his pottery and herbs, metalwork and video, commemorating his wife’s battle with cancer and his questioning of existence. Next door, Anselm Kiefer’s explosive installation of sunflowers, photos and letterpress fragments grapples with the fraught legacy of postwar Germany where he grew up amid the tainted rubble.

The middle floor – darker, subdivided, more intimate – evokes memory. Here you’ll find Apichapong Weerasethakul’s film of an abandoned hotel bedroom and the kinetic ‘Lover’s Bed’ of Rebecca Horn. Risque slides by Nobuyoshi Araki contrast with covers of the New York Times spray painted by Shu Shibuya to express the personal and collective impacts from each day’s sunrise. Outside enlargements span a wall the length of the museum. Most mesmerising is Somboon Homtienthonong’s lying in state of ornate Lanna temple pillars, which take on the aura of giant sacred bones.

Appropriately to this memory floor, a room offers glimpses of ‘Vanishing Bangkok’ by Petch’s father Surat Osathanugrah. Surat was a keen photographer and a visible presence in Thai arts. He founded Bangkok University and spawned an artistic dynasty now in its third generation.

The Osathanugrah family own Osothspa, the pharmaceuticals and drinks conglomerate founded in1891. Dib crests a corporate wave that is transforming Thai art. Earlier, Jim Thompson’s collection was augmented by the related Jim Thompson Art Centre, Jim Thompson Farm, MAIIAM in Chiang Mai and MAIELIE in Khon Kaen. In the 1980s-90s, banks invested in neo-traditional art, a style found in MOCA, the Museum of Contemporary Art founded by the DTAC telecom tycoon Boonchai Bencharongkul. Since 2018, ThaiBev has sponsored the Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB). The family behind CP then opened Bangkok Kunsthalle and Khao Yai Art Forest, while Central Department Stores joined in with deCentral gallery near Dib in Phrakhanong.

Private art museums reveal the collector’s personal taste. They aren’t survey institutions like the National Art Gallery, which languishes unfinished at Thailand Cultural Centre. And they lack the public role of Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC), which sprung from grassroots artist activism.

After decades of the bureaucracy managing culture as an ideological expression of ’Thainess,’ corporations might emerge as new art gatekeepers with billion-dollar reputations to safeguard. Such serious funding and splendid platforms could sway artists away from risk towards acceptable art spectacle. It remains to be seen whether this enables more Thai artists to make a living from art, or entrenches established ‘artist brands.’ Happily, Dib and MOCA both buy new art.

‘I would say contemporary art is not for everybody, but it is for anybody who is willing to open their mind,’ Miwako says. While the art is magnificent, it’s nearly all conceptual and not mass market taste. But Dib has a community and family outreach program, partly at its linked site in Phromphong designed by Thai architects Supermachine.

Dib is only the third museum in the world to have an advanced AI guiding app, ARTLAS. Free and multi-lingual, it can tailor a Dib route to suit your timeframe, age, interests, mobility and art knowledge, with special settings for kids and experts. It can identify exhibits and provide as much or little information that you like.

Those ambitions face a hurdle: Dib’s really expensive. Thais pay B550 and foreigners B700. That is more than many bigger museums in wealthy countries. The investment here is huge, but it’s hard to fathom the maths amid a global cost-of-living crisis. Halving the prices would far more than double the traffic. High pricing lessens the chance of return visits, not joining friends sent here, and may crimp revisits for the next exhibition in August 2026. Many complain that there aren’t family, annual or lifetime passes. That said, the exceptional quality makes it a must-see.

Thailand has long traded on its traditions but neglected the cultural tourists who’d fly here for a musical, a museum, an exhibition. People have come just for biennales, and now they have a year-round drawcard for art tourists. Meanwhile, Bangkokians no longer have to fly abroad to see international contemporary art. Go on, take a dip into Dib.