If you wanted to make a film, how would you promote it? A trailer, perhaps. A poster campaign. A carefully timed festival debut. What you probably wouldn’t think of – unless you’re Note Pongsuang – is opening a bar.

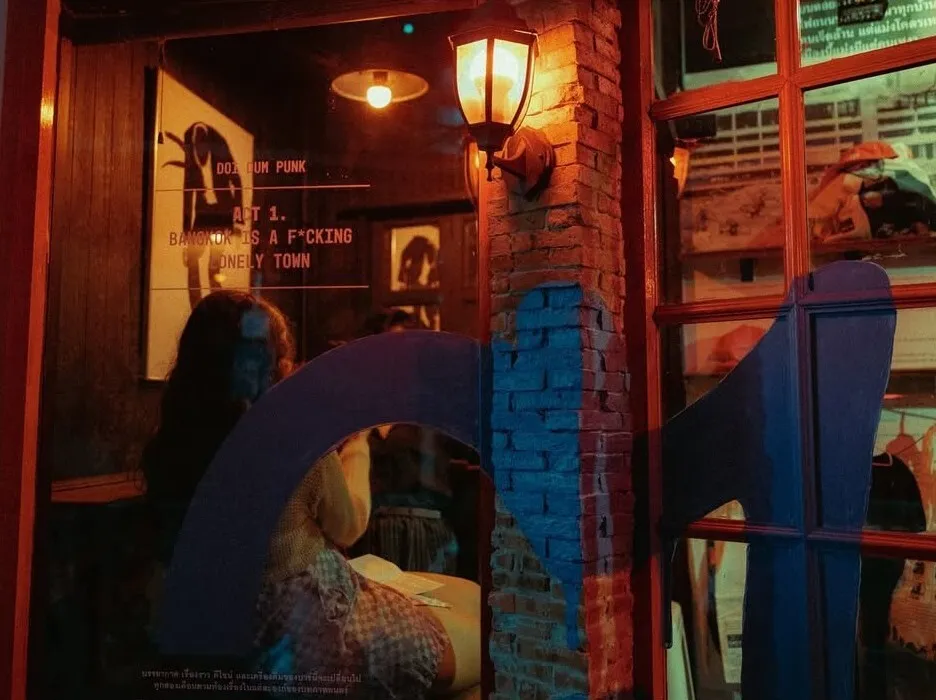

I’m sitting inside Doi Dum Punk, the small bar decorated with bits of art on the wall, newspaper pasted as wallpaper and a guitar that looks like it’s never been touched. Outside, a tag hangs on an electric post declaring, almost gleefully, ‘fun fact, punk is dead’.

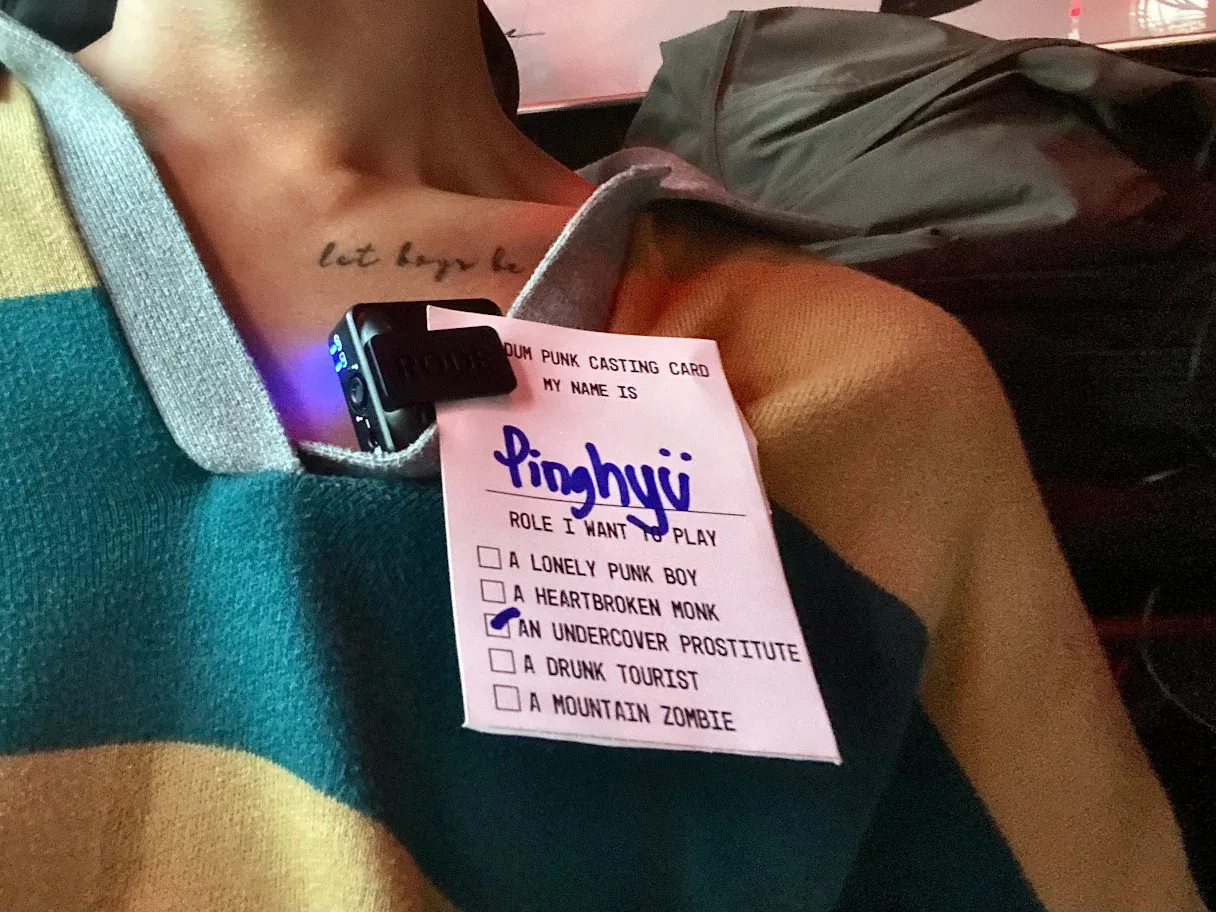

Before sitting down, Note handed me a hand-drawn tag with a list of movie roles to choose from: a lonely punk boy, a heartbreak monk, a drunk tourist or a mountain zombie. Of course, I go for an ‘undercover prostitute’. Now, with a gin and tonic in hand, I watch him talk through this improbable scheme with the easy certainty of someone who has, more than once, bent Bangkok nightlife into new shapes.

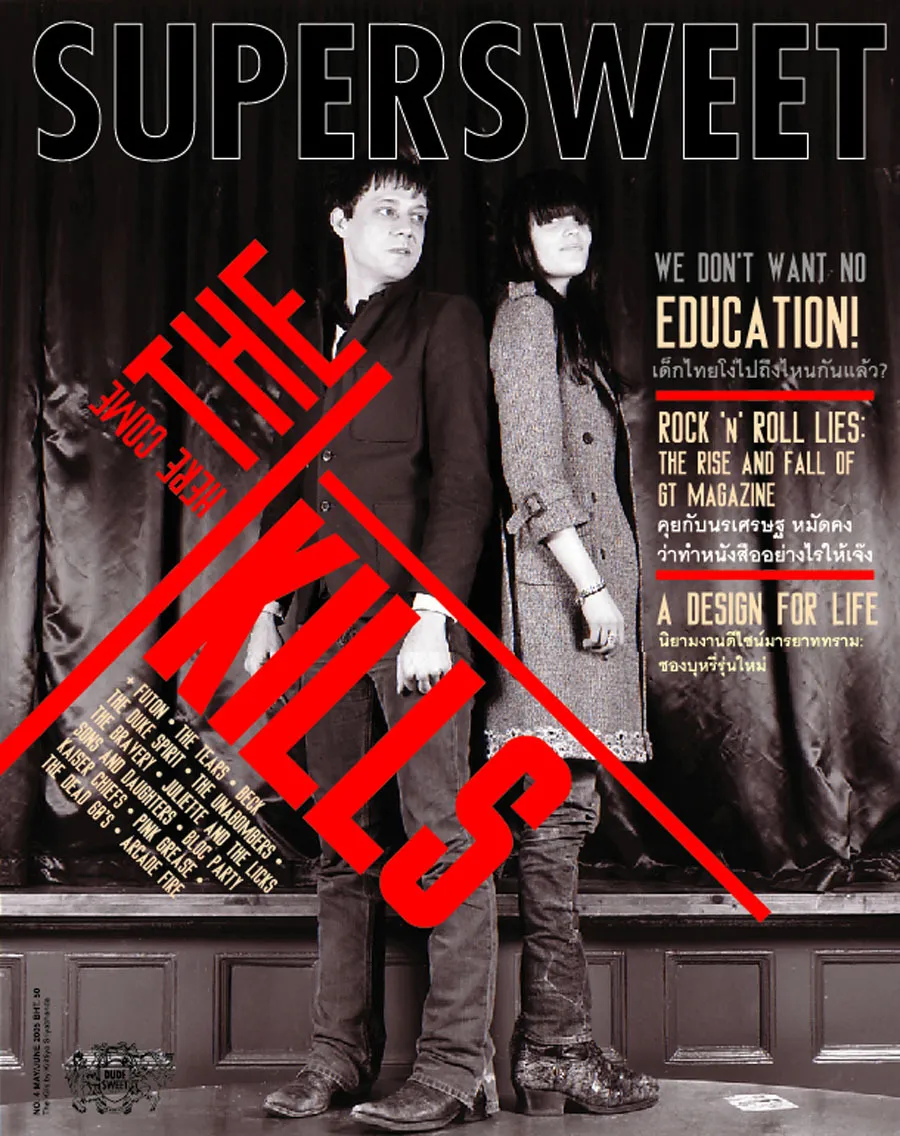

Note is the founder of Dudesweet, a name still uttered like an inside joke that turned into a generational movement, and of National Bar, a space that looks like it tumbled out of his Silpakorn sketchbooks. As a living archive of the city’s indie scene, and for me – someone who grew up hearing stories of early-2000s warehouse parties with badly photocopied flyers – it feels like slipping behind the curtain of a myth. His legend is well known, but Doi Dum Punk, a pop-up bar designed to fund and promote a screenplay, is the reason I’m here with a camera rolling, notebook in hand, and questions queued up.

‘It’s mad,’ I think, ‘but it’s also very, very sweet.’

The birth of a word

Note doesn’t claim credit for coining ‘dek naew’ – Bangkok’s shorthand for cool kid – but he knows exactly when the phrase escaped into public life.

‘Back in the day, ‘dek naew’ was meant as an insult,’ he tells me. ‘It came from ‘dek alter’ – short for alternative kid – because we were influenced by 90s music. It wasn’t glamorous at all.’

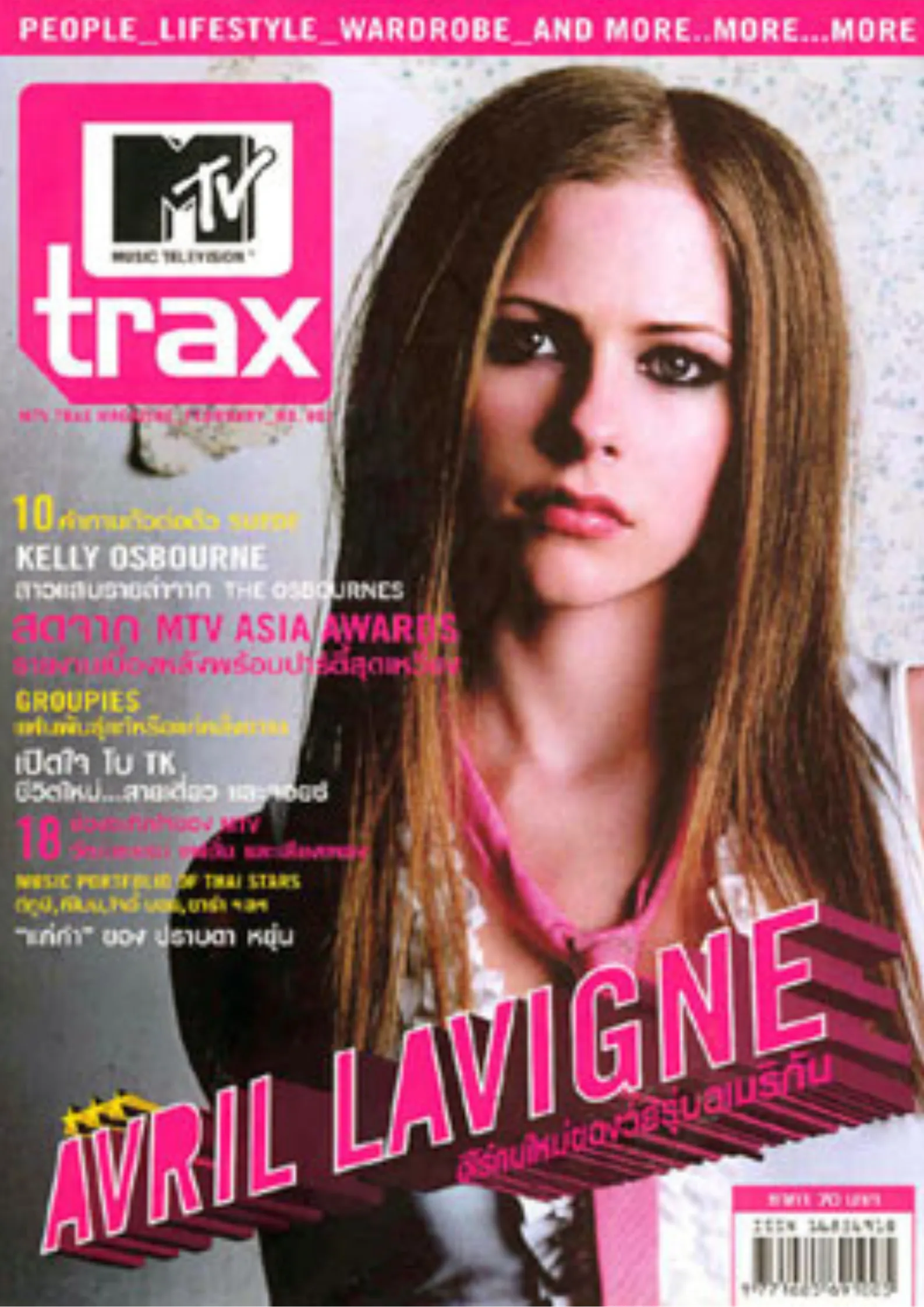

At the time, Note was writing for MTV Trax Magazine. In 2004, he published an article documenting teenage life, headlined simply: The Life of Dek Naew. ‘That was when it really stuck,’ he recalls. The word has lingered, bending with the years. ‘Fast forward to now, the music has changed, but the feeling is still there. People still want to belong to something, even if they call it by a different name.’

As he says this, I think of how easily slang gets discarded, how quickly a phrase can wither, and yet this one still clings on. Maybe because it wasn’t just a word – it was a mirror.

The accidental institution

When I ask about Dudesweet, now 23 years old, he laughs. ‘Old enough to be a university graduate with regrets,’ I tease. He nods.

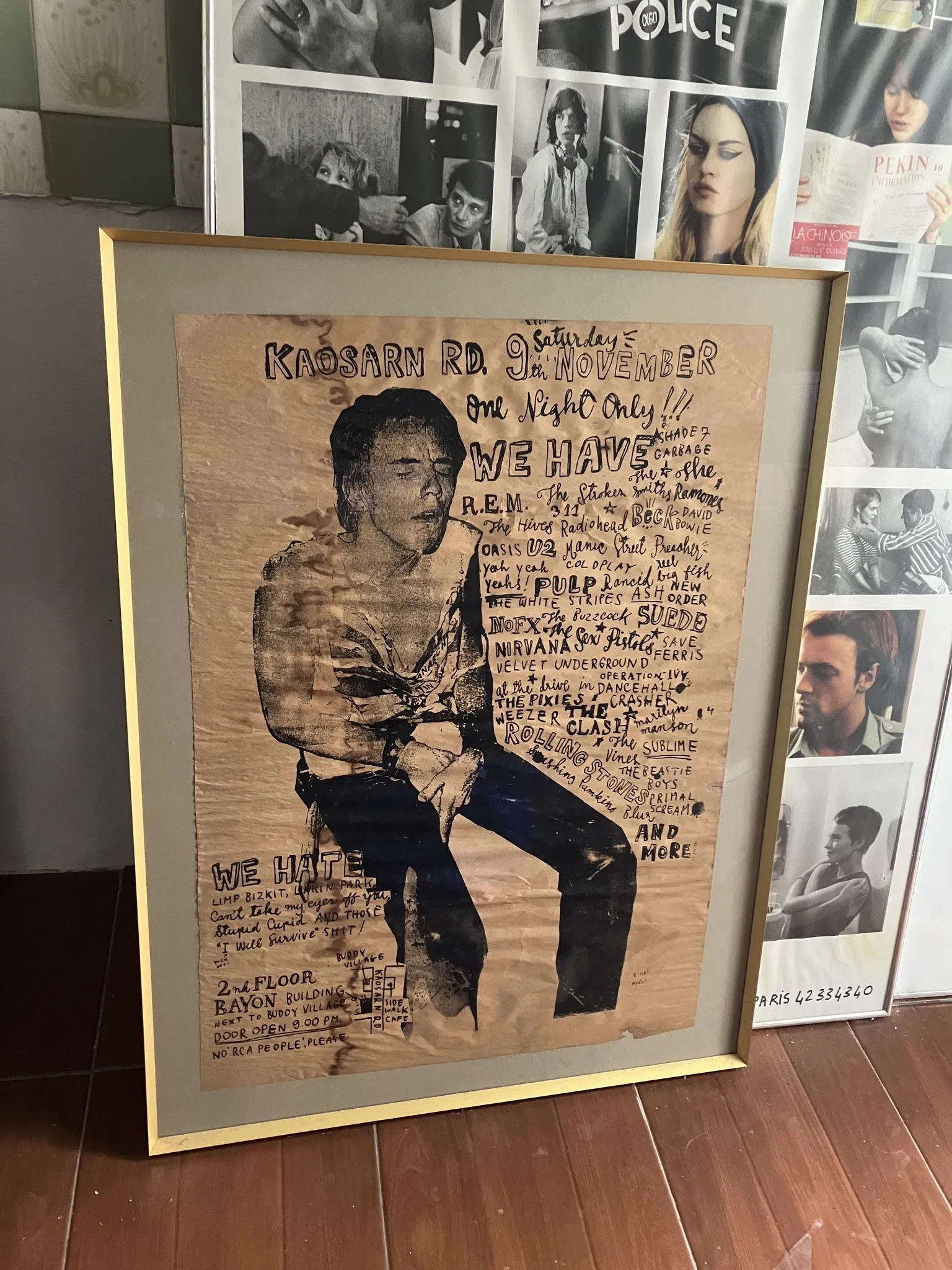

‘It started as just a party with friends,’ he says. ‘Cheap beers, a bit of art. The poster even said ‘one night only.’

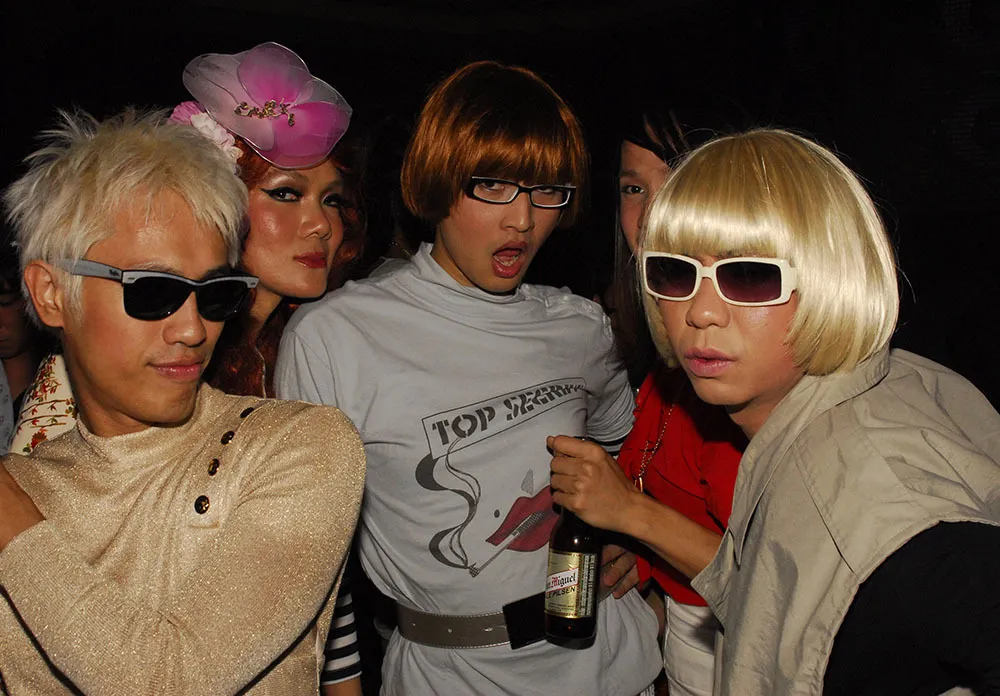

In the early years, there were never more than 80 punters at a Dudesweet night. Flyers were Xeroxed, posters hand-screened, and the only algorithm was word of mouth. But among art students and young musicians, the stories spread – of parties on rooftops, in abandoned hospitals, in places that weren’t meant to be dance floors. By the third year, fashion designers and bands who’d never attended were still talking about them.

‘From 80 people, it grew. And I think what never changed is the attitude. The Gen X spirit of ‘I don’t give a fuck.’ We never had things easy, so just fuck it.’

I envy that clarity. For my generation, rebellion often feels curated, pre-approved by algorithms. For his, it was sweaty rooms and trial by fire exits.

Strange homes and stranger nights

One thing about Dudesweet: no venue was too odd. Airplane cabins. Rooftops with dodgy electrics. Abandoned hospitals that looked like film sets even before the crowds arrived.

‘The most chaotic was on the plane,’ Note remembers. ‘You don’t know what you’re allowed to do up there. And some venues didn’t even have AC.’

Still, when I ask what space feels like ‘home’, his answer lands softly. ‘Here, Doi Dum Punk. My house is nearby. It feels right.’

It’s strange to hear someone who once staged chaos in defunct buildings describe a sense of home, but perhaps that’s the point: you have to burn through a few ridiculous ideas before finding the one that sticks.

Notes from the National

Before Doi Dum Punk, there was National Bar – his more permanent love letter to himself.

‘I found my old Silpakorn sketchbooks when I was cleaning,’ he says. ‘Ideas I drew when I was 19. I just stole from myself.’

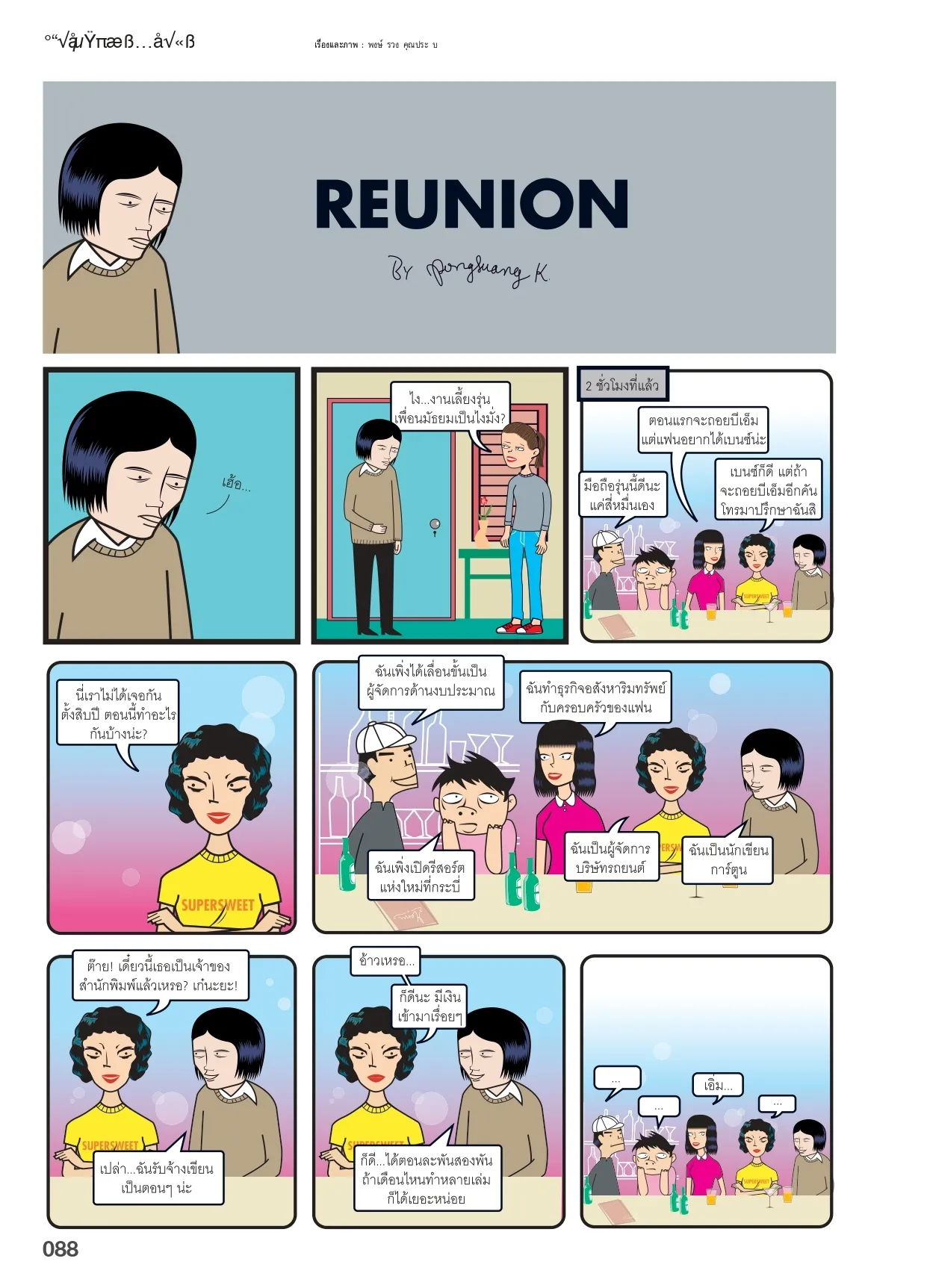

The result is a space that blurs diary, gallery and drinking den. Its Instagram stories, too, became unexpectedly famous – cartoon strips drawn in his spare time, later reborn as NFTs. And his favourite? Reunion.

‘Actually, my first job was as a cartoonist for Proud Magazine,’ he explains.

‘When you’re young, you dislike so many things – so the jokes came from that. City life, politics. I rediscovered those sketches, and it all came back.’

Even here, I sense the same pattern: pulling from archives, remixing the past until it feels current again. Perhaps the true Note formula is less invention than resurrection.

Photographing generations

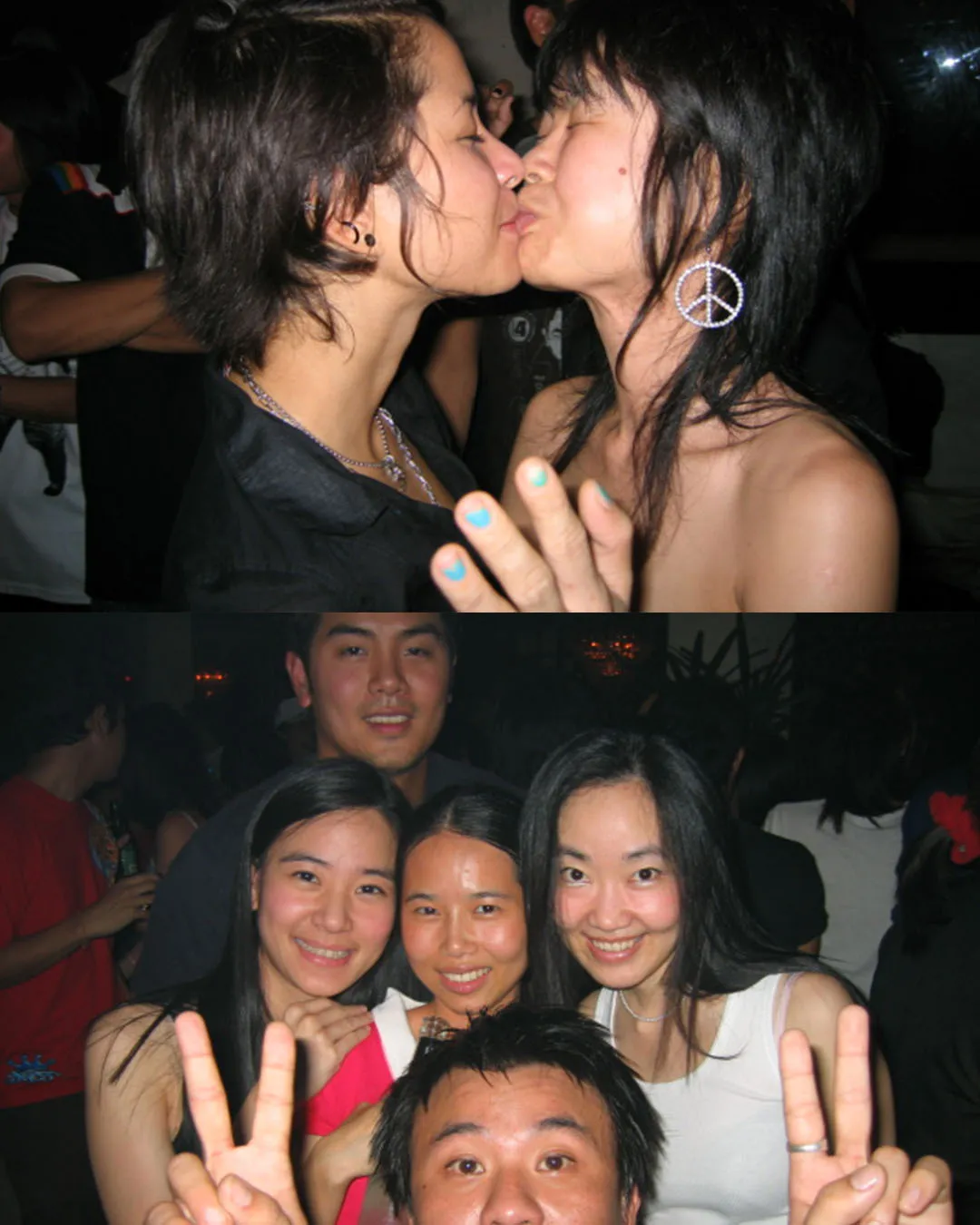

We talk about the thousands of photos he’s taken through Dudesweet years – grainy portraits, forgotten outfits, strangers posed as if they knew they’d be remembered.

‘I’m working on a photobook now,’ he says. ‘It’s called Wake Up, Party, Sleep, Repeat. But it’s not just drunk people dancing. It’s history. You see trends, make-up styles, even conflicts. The first year smoking was banned indoors – you see that too.’

He speaks like an archivist, not a promoter. A city’s hidden curriculum taught in eyeliner, hair dye, and who chose to stand near the speakers.

For me, this is the most moving part. It isn’t nostalgia – it’s proof. A visual ledger of a Bangkok that shapeshifted every few months, but always found its way back to the dance floor.

Doi Dum Punk: A bar that wants to be a film

Finally, we arrive at the reason I’m here. Doi Dum Punk, the pop-up bar staged as both a performance and a fundraiser, is perhaps his boldest idea yet.

‘The bar will run for six months, July to December,’ Note explains. ‘It’s a way to promote the screenplay and raise funds for Doi Dum Punk, a coming-of-age comedy. It’s still just a script, but hopefully one day it will be a real film.’

The timing feels uncanny. As of now, the Thai film scene is going up, up, up. A Useful Ghost just won the Critics’ Week section at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival, while Human Resource picked up the Fondazione Fai Persona Lavoro Ambiente Award in Venice. Against this backdrop, Note’s project doesn’t seem far-fetched – it feels like a dare to keep pace with a national moment.

Each act of the screenplay shapes the bar itself: music, atmosphere, decor, drinks, even scent. Every two months, the entire space transforms. Alongside this, there are talks with filmmakers, casual discussions on cinema and storytelling, little collisions that might plant future projects.

‘Of course, a pop-up bar can’t fund an entire film,’ he admits. ‘But it can build an audience, make people part of the process from the beginning. It’s a meeting point – for writers, film lovers, dreamers.’

And if the goal slips away? He shrugs. ‘Then I’ll go full indie. Cheap camera, low-cost production, whatever it takes. Better to make it rough than not make it at all.’

I ask if the bar has influenced the script. He grins. ‘Yes. People come in, they talk, they share stories. I collect ideas, add them in. It’s alive.’

Why not just release a trailer? Why ask people to step inside an unfinished idea?

‘Because this way I meet filmmakers, funders, curious people. And it doesn’t cost much. The bar tells the story better than a poster ever could.’

He’s right. Sitting there, I feel part of something still forming. It’s not just promotion – it’s immersion.

As our conversation winds down, I realise Doi Dum Punk is not really a bar and not yet a film. It’s a hinge: a liminal experiment where nightlife becomes cinema, where parties bleed into scripts, where the future is drafted in beer rings on tabletops.

In a way, it’s the purest continuation of Dudesweet’s original mission. Cheap drinks, strange locations, art stitched into the fabric of a night. Except this time, the story doesn’t end when the lights go up.

‘Maybe it works, maybe it doesn’t,’ Note shrugs. ‘But at least it’s something new.’

With the conversation over and bellies full of beer, we witnessed two accidental motorbike crashes on the rainy soi outside. I walk out into Bangkok’s humidity with the phrase still looping in my head. Something new. For a city that thrives on repetition – new malls, new rooftops, new DJs – Doi Dum Punk feels like an act of stubborn imagination. A reminder that culture doesn’t just arrive; sometimes it gets built, brick by brick, bar by bar, draft by draft.

And maybe, if we’re lucky, reel by reel.