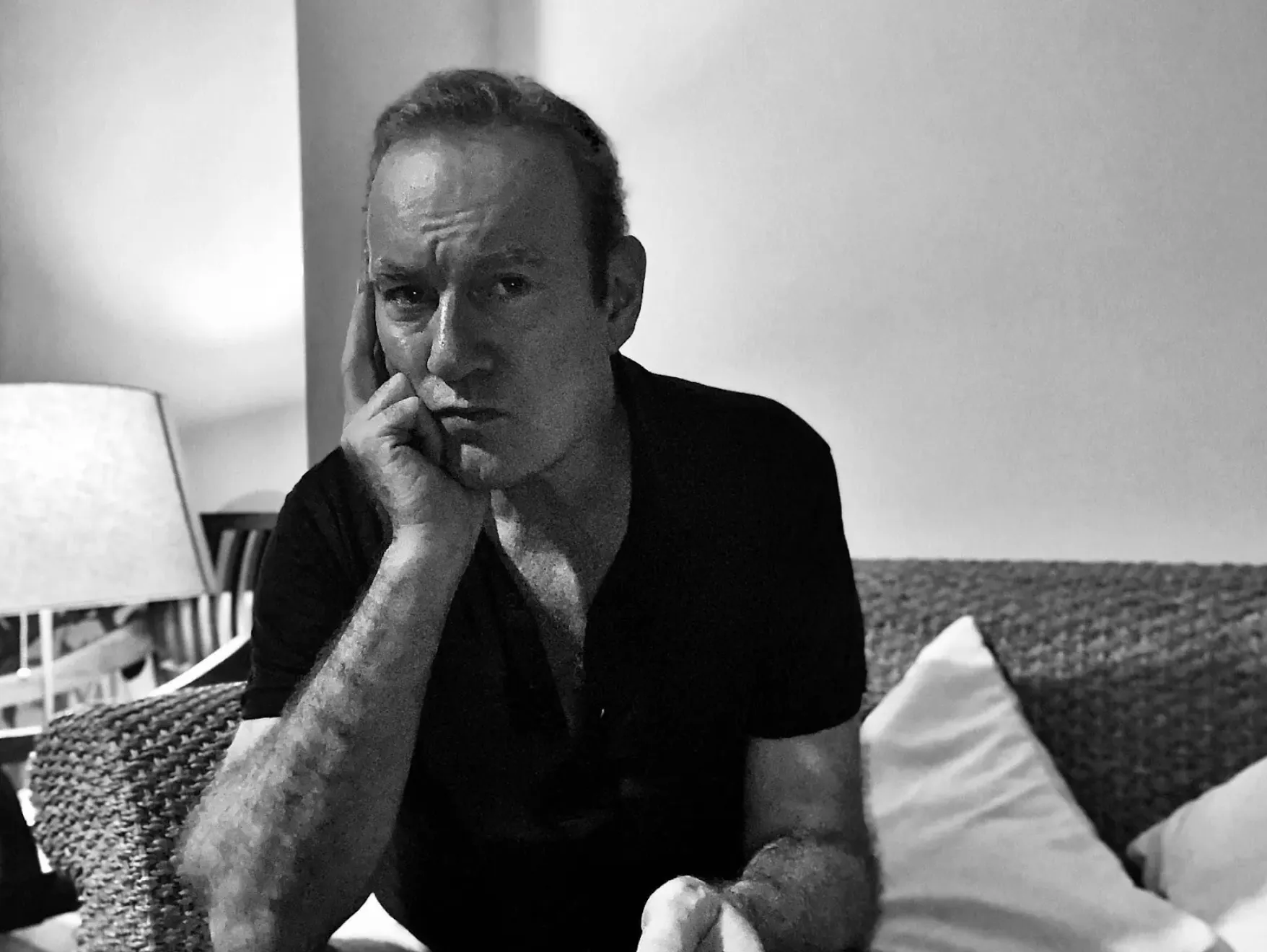

Since its premier at the 52nd Telluride Film Festival in Colorado last month, tantalising images and reviews of Colin Farrell in Ballad of a Small Player have been circulating online. Based on the 2014 novel by Lawrence Osborne and directed by Edward Berger, whose 2022 epic All Quiet on the Western Front landed four Academy Awards, Ballad of a Small Player is set to bring a fresh view of Macau to a global audience.

‘They really followed the book in terms of locations,’ says the novel’s author Lawrence Osborne, from his apartment in Sukhumvit.

For Osborne, ‘authenticity of place is the secret to authenticity of story,’ and he’d always felt, ‘the kaleidoscope of the exploding city has not been rendered in film before.’

‘Berger,’ he says, ‘understood that he had to capture the texture of Macau.’

Osborne is yet to see the film adaptation, which Netflix is closely guarding until its official release in October, although he did get to watch some scenes being shot.

The story follows Lord Doyle, a fraudulent British gambler drifting through ‘Asia’s Las Vegas.’

‘It’s very autobiographical. A lot of that character is about poverty and failure. When I watched Colin Farrell going through the lines on the set, I saw myself 20 years ago.’

As Osborne tells it, he discovered Macau after being hired as a reporter for The New York Times, a job that followed years of poverty and failure as a down-on-his-luck writer.

‘I was in the wasteland in the ‘90s. Eventually, a friend called me into the Times office and said, I can save you, but you need to have two beats nobody else wants. Criminology in America and psychiatry in the developing world.’

The latter beat brought Osborne to East Asia, which has subsequently served as the setting for many of his best-known works.

‘Whenever I was working in the region, I would base myself in Bangkok.’

It was in those years that Osborne walked the city’s canals, befriending down-and-out expatriates and street urchins, the lowlife cast of his non-fiction hymn to the city Bangkok Days (2009).

Yet it was that chagrin necessity, ‘the visa run,’ that introduced him to the Portuguese colonial outpost turned neon-hued gaming mecca on the rump of the Chinese dragon.

‘I always felt Las Vegas was the most depressing place on the planet. But in the lobby of the Lisoba [Macau’s oldest casino] they have these giant statues of Guanyin, the goddess of mercy. I thought it was strange that Stanley Ho felt the need to put all this symbolism in his hotel, as if to remind people of the supernatural element of gambling.’

Macau’s curious blend of the commercial and spectral enchanted Osborne, inspiring a ghost story through line: the fact that Lord Doyle is a haunted man who is eventually saved by Chinese siren Dao-Ming (played by Fala Chen in the film).

‘Reading some of the first reviews, the critics don’t understand that this is an Asian ghost story. It’s just outside of their frame of reference. They don’t get the reference to hungry ghosts or why Doyle is wearing green.’

To understand the mind of a gambler, Osborne started gambling.

‘Initially, I had no plan to write a book. I just wanted to know what it felt like. I played baccarat, which requires no skill, and I actually lost money. But I came to realise gamblers enjoyed losing because it provides a leave of freewill.’

At the time, Osborne was still based state-side, visiting Asia as a journalist. But by 2009, the pressure of life in the Big Apple was starting to wear on the English scribe.

He departed America, and in 2012, made Bangkok his home.

‘I came to Thailand and went to an all-night supermarket, then to a little bar. Out on the street, it was pouring rain and there were two African girls dancing. I thought, this is amazing, nobody cares. There’s a sort of wild freedom in this city you just don’t get in many places.’

Realising he could ‘live here’ at a fraction of New York’s costs, Osborne has been able to focus on fiction, churning out a number of critically-acclaimed novels including 2020’s The Glass Kingdom, which is set in his building during the political crisis of 2013-2014.

‘I wanted to write a book about women in Thailand that weren’t bar girls.’

Like so much of his writing, the subject matter is a runaway expat, in this case Sarah Mullins, who flees America with a suitcase full of cash only to get entangled in the lives of a community living in an upscale apartment complex in central Bangkok.

Although Osborne dislikes the term ‘travel writer’ claiming his works of non-fiction are ‘anti-travel books,’ years working as a journalist have imbued him with descriptive tendencies that border on cinematic. The Glass Kingdom is no exception.

‘She was alone among the flies, and the moon was still high above the dirty white skyscrapers of Bangkok,’ he writes in the opening chapter.

As with Macau, Osborne is keen to bring his vision of Bangkok to global screens. A script for The Glass Kingdom is currently in progress, and this time, he is taking a hands-on role with his new production company Java Road founded with Ballad of the Small Player producer Mike Goodridge and Nicholas Simon of Indochina Productions.

‘One of the reasons we started this company was to get away from being dictated to by Hollywood studios.’

But, after 13 years living in the Thai capital, does he still feel inspired by the city?

‘It’s no longer Bangkok Days. But as an urban knitting board, it’s unbelievable. It’s so textured and complex you can never really get to the bottom of it.’

As with Macau, Osborne senses a close proximity with the spirit world, even at the heart of the urban jungle.

‘A lot of Thais would say they think that this is a world of ghosts and we are just temporarily inhabiting it. That’s a beautiful conceit, and when you are close to people who believe in those things, you also come to believe in them too.’

He says he still doesn’t know many expats and lives a life not entirely estranged from the night prowler depicted in Bangkok Days, although a road accident means he now has to rely on his Yamaha Filano to get around.

‘I still find it a very mysterious city. I like to go to the ceremonial centre where all the palaces and temples are. In the daytime it’s jammed with tourists but at night you can experience this late-18th , early-19th century city, which is what it is at its core, all alone.’