Here we are again, only this time we’ve landed at Funky Lam Kitchen – a modern Laotian menu that doesn’t flinch from bold, full-throttle flavours. The cocktails and the wine list aren’t there to soothe but to spar, chosen deliberately to hold their ground against the fire. Step inside and you’re in a space that feels like someone’s memories turned into design: a renovated shophouse lined with old BMW motorbikes, walls hung with images that hint at histories both personal and political.

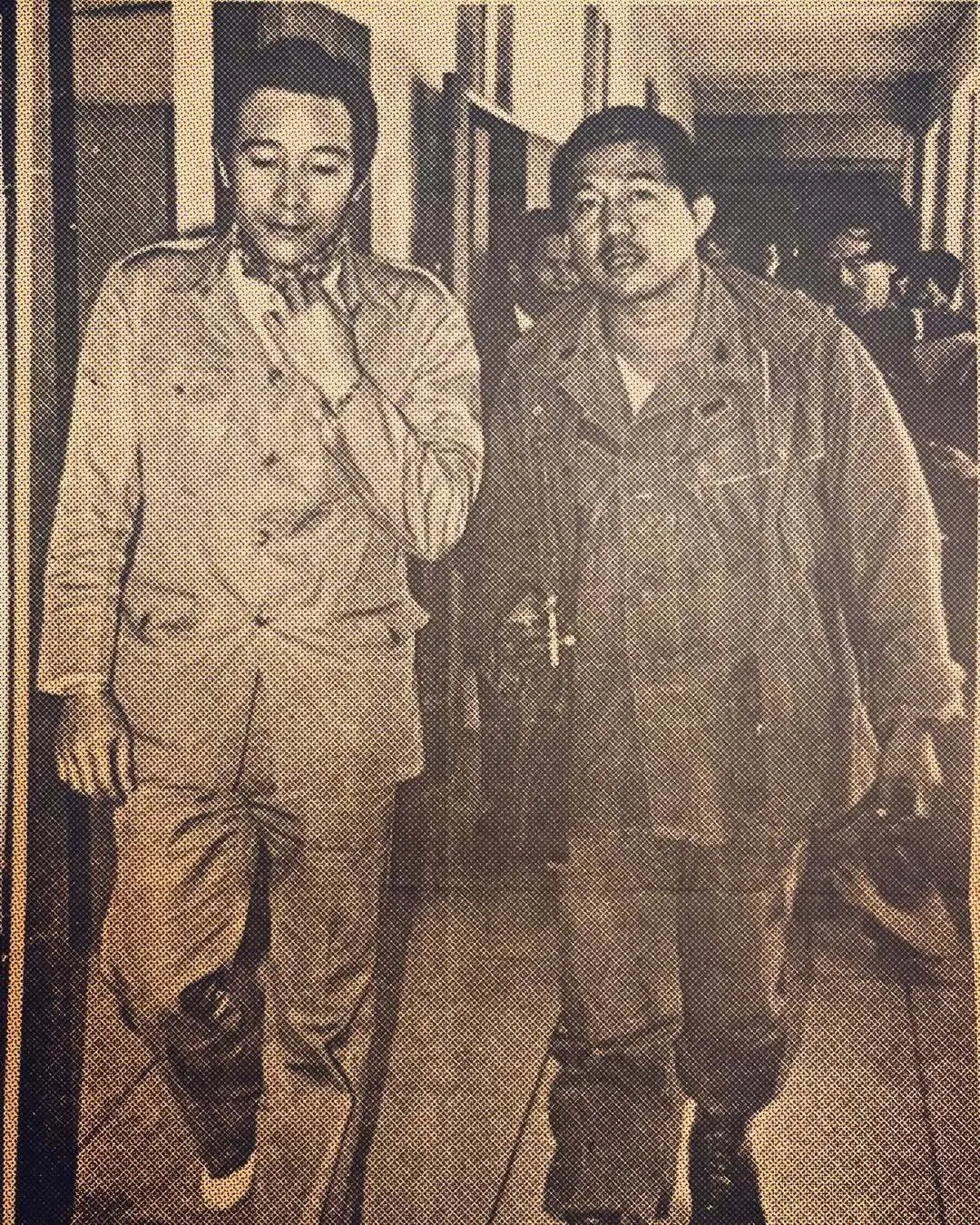

Funky Lam isn’t simply another addition to Bangkok’s dining map. It’s the dream realised by Sanya Souvanna Phouma – the man who gave the city Bed Supperclub, Maggie Choo’s and Sing Sing – alongside his fellow Laotian partner Saya Na Champassak, whose grandmother, once the princess of the south, was famed for menus devised with the palace chef for royal tables. Together, they’ve built something more than a restaurant: a love letter to Lao cuisine, a revival staged with funk, grit and affection.

And that’s why I’m here, to ask how two men who grew up in Paris, haunted by both French kitchens, the stories tucked between plates of olam and glasses of Beer Lao and Laotian memories, ended up here.

The inheritance of nightlife and airways

‘It’s in my DNA,’ Sanya says when I ask if his father’s club influenced him. His father, Prince Panya Souvanna Phouma – Harvard graduate, son of a Prime Minister, head of Royal Laos Air – once co-owned The Third Eye, a psychedelic club in Vientiane during the late 60s. ‘My dad walked into Maggie Choo’s one night, saw the umbrellas on the ceiling and told me it reminded him of The Third Eye. I hadn’t even realised I’d recreated something he’d already lived.’

The parallel is uncanny, but also inevitable. Sanya has spent decades shaping Bangkok’s nightlife with the kind of theatricality that makes a club feel more like a performance.

Saya’s lineage is no less dramatic. His grandfather, Prince Boun Oum, renounced his rights to the Champasak throne and launched Boun Oum Airways – entangled with Air America and the logistics of war. ‘He was an adventurer, a fighter,’ Saya says. ‘He used planes to move supplies – even medical aid – during the Vietnam war. That pioneering streak? I guess I inherited it. There’s a little gamble in everything I do.’

It shows. In the way they talk, there’s a refusal to play it safe, as if legacy itself demands boldness.

Paris, with Laotian eyes

Both men grew up in France, but never entirely fit in. Paris gave them culture, language and the culinary confidence of a capital where Asian food is stitched into the neighbourhoods. Yet, they were always seen – by others, and perhaps by themselves – as outsiders.

‘The French put us all in the same pot,’ Saya shrugs. ‘Vietnamese, Cambodian, Lao – for them, it was just ‘Asian’.’

Saya remembers being sent by his grandmother to scour Parisian markets for the ingredients she couldn’t find. ‘She’d adapt, cook with what was available – European produce, but Lao recipes. That’s how you preserve identity, you improvise.’

Sanya calls it a gift.

“Growing up in Paris gave me a cultural education I’ll always be grateful for. And the Asian food scene there, in places like Triangle de Choisy, it was rich, all-encompassing. We grew up eating everything.”

Between them, Paris was both home and not-home, a place that gave them vision but never quite a resting place.

Building something together

The idea of Funky Lam was less of a lightbulb moment, more of a slow insistence. Both men had returned to Southeast Asia in the late ‘90s, trying to reconnect with their roots. Bangkok, they decided, was the place to do it.’

“We were never fully French, never fully Lao,’ Sanya tells me. ‘But Thailand gave us the chance to explore that middle space.”

Saya nods.

‘We wanted to create something authentic. Not royal Lao cuisine, not nostalgic recreations, but the kind of food people actually eat, the recipes passed down at family tables.’

That’s how Funky Lam came to life. More than a restaurant, it became a vessel for memory – an answer to questions of identity disguised as bowls of soup and smokey grills.

Naming the Funk

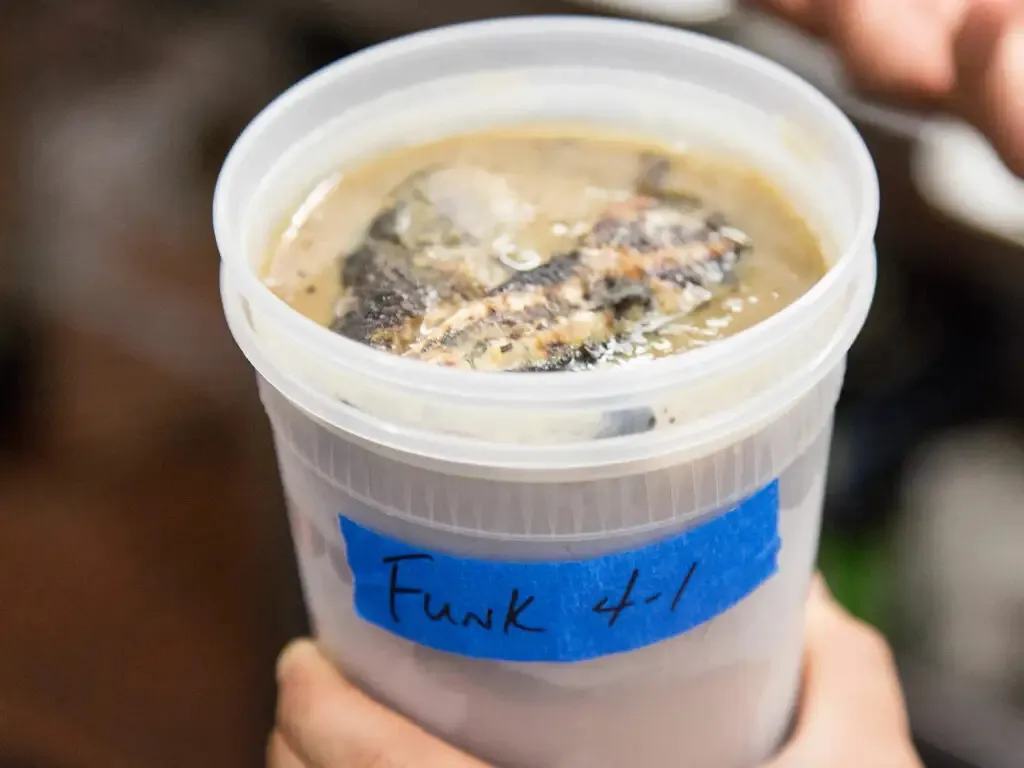

The name itself could be an inside joke. ‘I saw this documentary about a Lao restaurant in New York called Khe Yo,’ Sanya explains. ‘The chef, Phet, would make ‘pla daek’

– fermented fish – but he’d kick everyone out of the kitchen first. When it was done, he’d label it ‘funk. That stayed with me. And ‘lam’ – well, in Lao it means music. Put together, it’s soul food, soul music. Funky Lam.’

It fits. The space is half kitchen, half party. A restaurant that refuses to be background noise.

When I ask them what dish best represents Funky Lam, they don’t hesitate. ‘Olam, from Luang Prabang,’ Sanya says. Saya jumps in with his own favourite: all the variety of Jeaw with sticky rice. ‘It’s a sharing dish. Sharing is caring – that’s Lao culture.’

If the name gestures at music, the menu is rhythm. Heat balanced with acidity, smoke tempered with sweetness. Food that speaks of rivers and forests but sits comfortably next to a bottle of natural wine.

Talat Noi, and what comes next

Choosing The Warehouse Talat Noi wasn’t a coincidence. ‘It’s the epicentre of art and food culture,’ Sanya says. The neighbourhood, with its low-rise warehouses and riverside grit, mirrors something of Vientiane. ‘It’s got character, less of the high-rises, more of the history.’

They’ve lived in Bangkok since 1997, long enough to watch it change. ‘This neighbourhood especially,’ Saya points out. ‘The creativity in the past five years, it’s been incredible.’

And what of the future? They grin when I ask what people won’t see coming.

“Rustic dishes, even more authentic ones. Maybe some royal recipes reimagined. Live music, unusual acts. And yes – another Funky Lam. In Cha-am, at SO/ Sofitel Hua Hin. We’re calling it Baan Funky Lam.”

The ambition is restless, but rooted. For all its motorcycles and cocktails, Funky Lam remains about family recipes and childhood memories, about two men trying to reclaim something lost and offer it back, hot and loud, to anyone who steps inside.

Restaurants, at their best, are time machines. They carry the weight of family, geography and politics without ever letting you forget the plate in front of you. Funky Lam is exactly that – a place where heritage becomes edible, where a grandmother’s market list in Paris meets the psychedelic swagger of ‘70s Vientiane, where two men who never fully belonged built a space that feels like home.

And maybe that’s the real trick. Lao food here isn’t a side note in a Southeast Asian culinary revival – it’s the headline. Funky Lam doesn’t whisper its identity, it sings it, funk and all.