There's a peculiar silence that follows when you tell someone 'I don't drink'. It lands awkwardly, like you've just admitted to something vaguely embarrassing. But that silence has been shrinking lately. Gen Z are leading a quiet revolution, choosing clear heads over hangovers and questioning why socialising has to revolve around a bottle. After lockdown rewired our habits, old rituals started looking a bit naff. Drinking less isn't just about health anymore – it's cultural. Which raises an obvious question: if you're not drinking, where the hell do you go in a city that's built on the mythology of nights out?

That's how I ended up deep inside Sammakorn Village, a residential labyrinth in Bangkok that's home to more than 6,500 households and, rather improbably, one of the most unusual bars in Asia. STØCKHØLME Sober Bar is Thailand's first alcohol-free bar and the first in Asia. It opens from 2pm-10pm, welcoming everyone from the sober-curious to families who rock up with dogs and teenagers in tow.

I'd expected earnest kombucha, wellness lectures and maybe a queue of yoga mats. Instead I walked into something warm and surprisingly mischievous, where cocktail shakers were working overtime and two people, Korranath 'Oak' Thamamnuaysuk and Weeree 'Wee' Yomjinda, greeted me like friends determined to prove that sobriety has never meant boring. What followed was two hours of tasting, chatting and mild existential questioning about what the word 'bar' actually means now.

A lifestyle shift you can actually feel

The more we talk about drinking less, the more it sounds like common sense rather than some grand statement. Lockdown forced us to examine our routines under harsh light, and many people realised a night out didn't require being off your face to feel genuine. Alcohol was just the default setting, not necessarily the desired one.

Walking into STØCKHØLME, I felt that mix of curiosity and self-consciousness that sober spaces can trigger. There's a minor panic that you'll be judged for expecting a buzz, even when you're not asking for one. But as I sat down, the room felt oddly familiar. The sounds were identical to any bar – ice clinking, muddlers working, quiet conversations – just without the gradual descent into slurred speech.

The bartender stood behind the counter, hands moving with the confidence of someone who's mixed thousands of drinks but none with alcohol. He told me sober bars have been spreading across Europe and the US for years. They're not novelties anymore but part of an emerging landscape where you can have a night out without the side-effects.

'People see us as a bar for everyone,' Oak said. Not a temple of restraint or a wellness lecture hall, but a space where you can gather without your personality being dictated by what you're drinking.

“We try to communicate that all our beverages are drinks used for socialising. We want people to come out more, have fun, have memories. We don't believe alcohol connects people because some wake up and can't remember.”

There was no judgement in his voice, just a simple observation. In that moment I got it: sober spaces don't remove pleasure, they restore attention.

The story behind the name

Before the drinks arrived, Oak explained the name. STØCKHØLME. It's actually a marriage of two words: stock and holme, meaning a small and rounded islet derived from the Old Norse 'holmr'. Together they become this imagined place, a storage house in the middle of water. A metaphor for safekeeping, or a tiny sanctuary where things can evolve without disturbance.

The bar started as a bottle-only takeaway project. Almost a hobby. When they found a suitable space, they built a modest storefront.

“We made it happen, and every struggle along the way was worth it”

Vee said, laughing. Now groups travel across Bangkok to try the drinks, hold meetings, bring their families or just sit quietly together. Some visit to curb cravings, others out of curiosity, some to reminisce.

Oak leaned forward as he described the prejudice that still clings to alcohol-free drinks. 'In Thailand, when we talk about zero percent alcohol beer, many say it's not beer. But abroad they accept it. You drink it the same way.' His voice has that familiar frustration of someone trying to open a door that others keep pushing shut.

But he doesn't frame his work as an argument. He sees it as translation. He and Vee are missionaries of understanding, not persuasion. They want non-alcoholic drinks to sit comfortably in everyday life, not as medical substitutes but as genuine social choices. Their eyes light up when talking about visitors who leave surprised, even relieved, that sobriety could taste this complex.

'Actually, what connects people and what many overlook is the stories and conversations they sit and talk about,' Oak said. It was the most accurate summary of their philosophy, delivered softly, like someone who's watched hundreds of strangers open up over glasses that contain no intoxicant except intention.

Fermentation without the fuzziness

Oak's journey into this world was accidental. He discovered he was allergic to alcohol 15 years ago. Instead of abandoning the craft entirely, he studied it more seriously. A WSET alumni (Wine and Spirit Education Trust), he trained as a wine sommelier before venturing into the broader world of fermentation, learning about distillation and the precise mathematics of flavour.

“I used to be stuck on the idea that wine must only be made from grapes, but now we see wine as a process.”

‘Ferment grapes and it's wine, ferment plums and it becomes plum liquor, ferment rice in Thailand and it's satho. We look in this direction.'

He talks about fermentation the way other people discuss architecture. Every ingredient is a building material, every process a blueprint. They create non-alcoholic gin and whiskey for zero percent cocktails, using distillation techniques that mimic the aromatic backbone of traditional spirits without the ethanol.

'We make non-alcoholic gin or whiskey for zero percent cocktails,' he says simply, as if the labour behind that sentence could be folded into one line.

The placebo effect and divine intoxication (yes, really)

What I felt, Oak explained, was the beginning of a placebo effect, or what he calls 'divine intoxication'. The phrase sounds dramatic but his explanation wasn't. 'Divine intoxication doesn't require being drunk. It's the effect of using all five senses – the sound, the atmosphere, the appearance, the touch of complex flavours with bitterness and astringency and the smell. At the beginning when we start drinking, the body doesn't know if there's alcohol because absorption hasn't happened yet, but the brain already processes that we're drunk.'

It made unsettling sense. Taste is often memory dressed up as pleasure, and our memories associate bitterness, smokiness or tannin with alcohol. When those notes appear, our mind completes the equation. It creates the sensation of drinking without the aftermath.

I sat there, glass in hand, feeling alert yet loosened, like someone had cleared away the static without dimming anything. This is the paradox of sober bars: you gain clarity but lose inhibition. You feel present without being rigid. The flavours lingered and I found myself more open in conversation, more amused by small details, more appreciative of the choreography behind every drink. It was intoxication translated through consciousness rather than chemistry.

More than wellness theatre

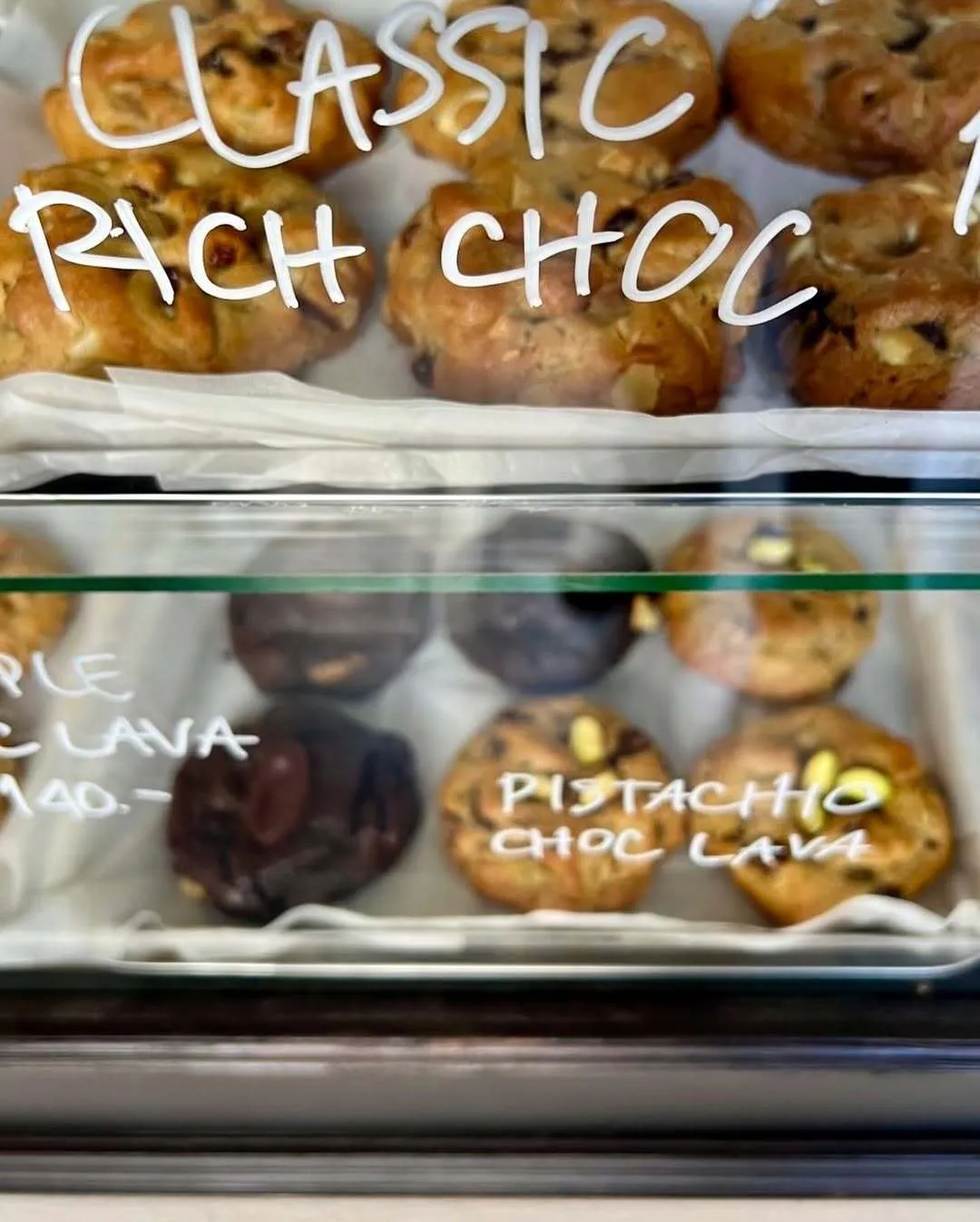

STØCKHØLME isn't some sterile wellness studio. There are pet treats on the counter because the bar is pet-friendly. Packaged snacks dangle from hooks next to shelves of beautifully labelled bottles. There are cookies from collaborative bakeries paired with drinks, as if the room itself wants to look after you. It has the comfort of someone's front porch disguised as a bar.

One surprise was the 'coffee shot' option. Oak can add cold-brew coffee to certain drinks, shifting the flavour from contemplative to mischievous in one pour. It's a clever nod to the bar's identity as a laboratory rather than a sanctuary from indulgence.

During my visit, I joke, 'Can we call it the vegan of the alcohol world?' Oak smiled but shook his head. 'It is that thing, correct. But better to call it vegetarian alcohol.' The phrase hung there, both playful and oddly precise.

“We have the most fun with groups who have never drunk alcohol before.”

Vee said. For them the bar becomes both classroom and stage, a place to witness flavours without baggage. Some visitors come wanting to quit. Others are tired of the predictable arc of a regular night out. Many just want something new that doesn't end with regret.

Every story felt different. The bar has quietly become an archive of modern life, filled with micro-portraits of people testing new ways of connecting. For Oak and Vee these stories aren't distractions from the work – they are the work. They recounted experiences with genuine excitement, as if every visitor adds another chapter.

Building a sober future, one glass at a time

Towards the end of our conversation, Oak's tone shifted. He spoke about the future with grounded optimism that felt refreshing. He doesn't want STØCKHØLME to become some precious rarity. 'We don't want to be the only shop where people come to learn,' he said. He hopes non-alcoholic drinks will become normal choices for Thai people, not curiosities requiring explanation.

He's not worried about competition. He welcomes it. The more sober bars that open, the richer the culture becomes. Knowledge should circulate, not be guarded. Sober spaces aren't meant to corner markets but open possibilities.

What struck me most is how naturally the bar embraces diversity. 'Everyone' isn't marketing speak here but an architectural principle. People of all genders, beliefs and lifestyles walk through without performing versions of themselves. The atmosphere is gentle enough to hold contradictions, dynamic enough to avoid the polite stiffness that sometimes shadows wellness spaces.

As I prepared to leave, I took a final sip. The flavours had softened but the clarity felt sharper than when I'd arrived. Sober bars challenge a very old myth: that alcohol is the glue of social life. Yet here I was, connected, amused, attentive. My senses didn't feel deprived – they felt amplified.

Walking back through the residential maze of Sammakorn Village, past the ordinary houses and parked motorbikes, I thought about how this quiet revolution is spreading. Bangkok is famous for nights that spill into morning, for rooftop bars and street-side drinking that never seems to stop. But perhaps there's space now for nights that end early but remain vivid, for experiences that don't require a hangover as proof they happened.

STØCKHØLME isn't dismantling nightlife. It's offering another route through it, one that doesn't punish you for wanting presence over oblivion. The bar proves that choosing not to drink isn't about restriction – it's about expansion. It's about discovering that the ritual, the gathering, the conversation were never actually about what was in the glass. They were about the people holding them.

And if you need proof that this works, just look at how far people are willing to travel into a residential village to find it. That silence after saying 'I don't drink'? It's getting quieter. And in its place, something more interesting is starting to speak.