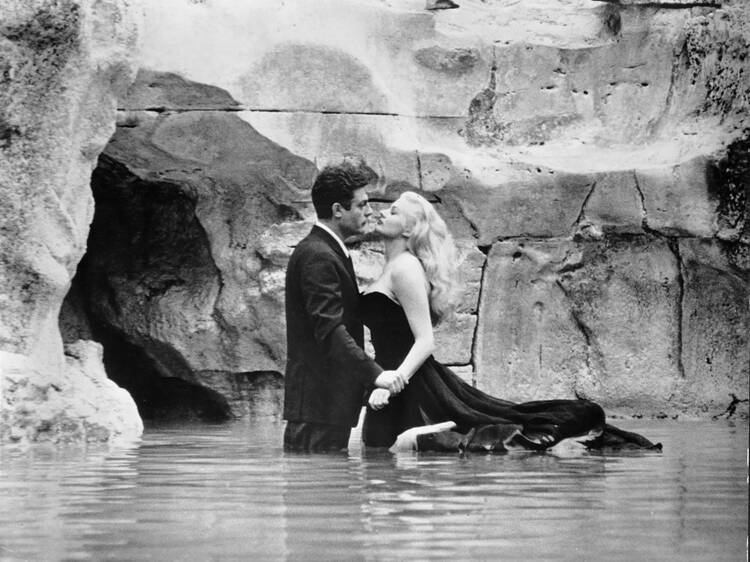

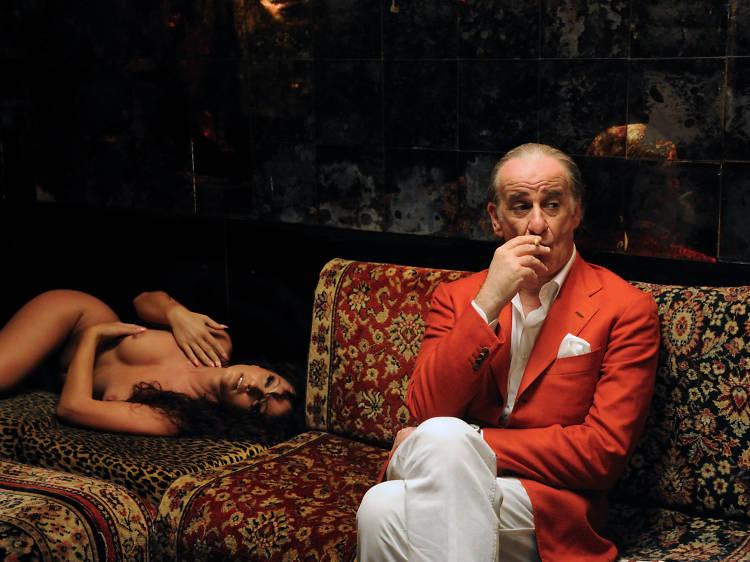

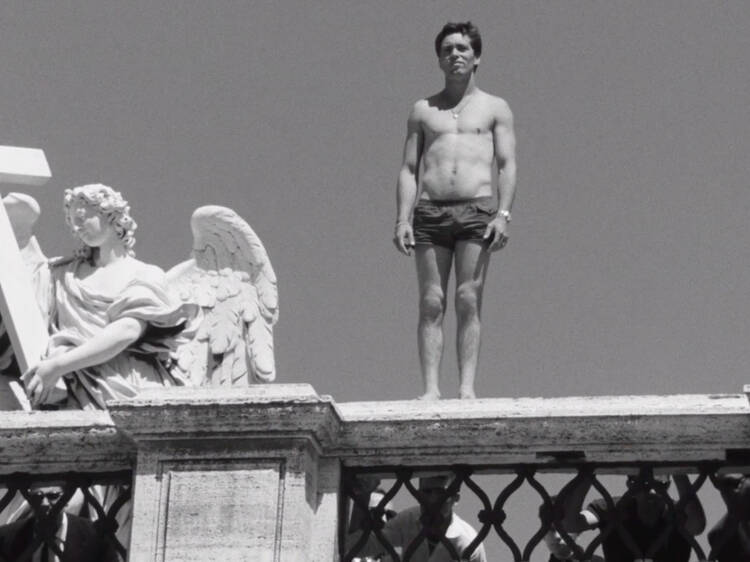

1. 8½ (1963)

Director: Federico Fellini

By the early ’60s, Federico Fellini had fully abandoned neorealism in favour of more symbolic, emotional and thematically complex filmmaking. His flights of fancy had grown increasingly fancier and flightier, reaching their peak with 8½, a kind of ‘psychological autobiography’ about a director in the throes of artistic inertia. Marcello Mastroianni is Fellini’s avatar, a filmmaker who can’t seem to make a movie and prefers to retreat into his own head, revelling in memories and fantasies while battling his own creative anxiety. The irony, of course, is that Fellini was more than capable of making a movie. And this is his most definitive.—Matthew Singer