[category]

[title]

On New Year’s Eve in 1966, undercover officers at the Black Cat Tavern in Silver Lake began to handcuff and beat the patrons and staff as everyone was exchanging celebratory midnight kisses. An estimated 14 people were arrested, many charged with lewd conduct and forced to register as sex offenders for the rest of their lives.

Other Silver Lake gay bars, including New Faces, a few doors down, were targeted the same evening. Two years before the Stonewall uprising, more than 200 people came together outside the Black Cat for one of the earliest U.S. LGBTQ-rights demonstrations. Picketers gathered on February 11, 1967, to peacefully protest the police raids that had been conducted weeks before. Alexei Romanoff, a former owner of New Faces, describes the Black Cat demonstration as a turning point. During a time in which homosexuality was illegal in most states, LGBTQ people developed elaborate codes and survival strategies to avoid arrest. But that February night, Romanoff says, the community stood up and fought back.

Now 82, he is the last surviving organizer of Personal Rights in Defense and Education (P.R.I.D.E.), one of the groups that helped stage the 1967 stand. We traveled back to that monumental moment with Romanoff.

How were the protests organized?

We didn’t have computers, we didn’t have cell phones, but what we did have was called a phone tree. One person would immediately call another 10 people and tell them what had happened, and then each of them would call 10 more people. It took us about two weeks to organize the protest. The Hub Bar [in Alhambra] was the only place that allowed us to meet. We were cautious. We kept moving the demonstration up and down the block so we couldn’t be charged with loitering. We had flyers printed up. People would ask what was going on. We’d give them a flyer, and if they dropped it, we would rush over, grab it and pick it up so we wouldn’t be considered to be littering.

What was the protest like?

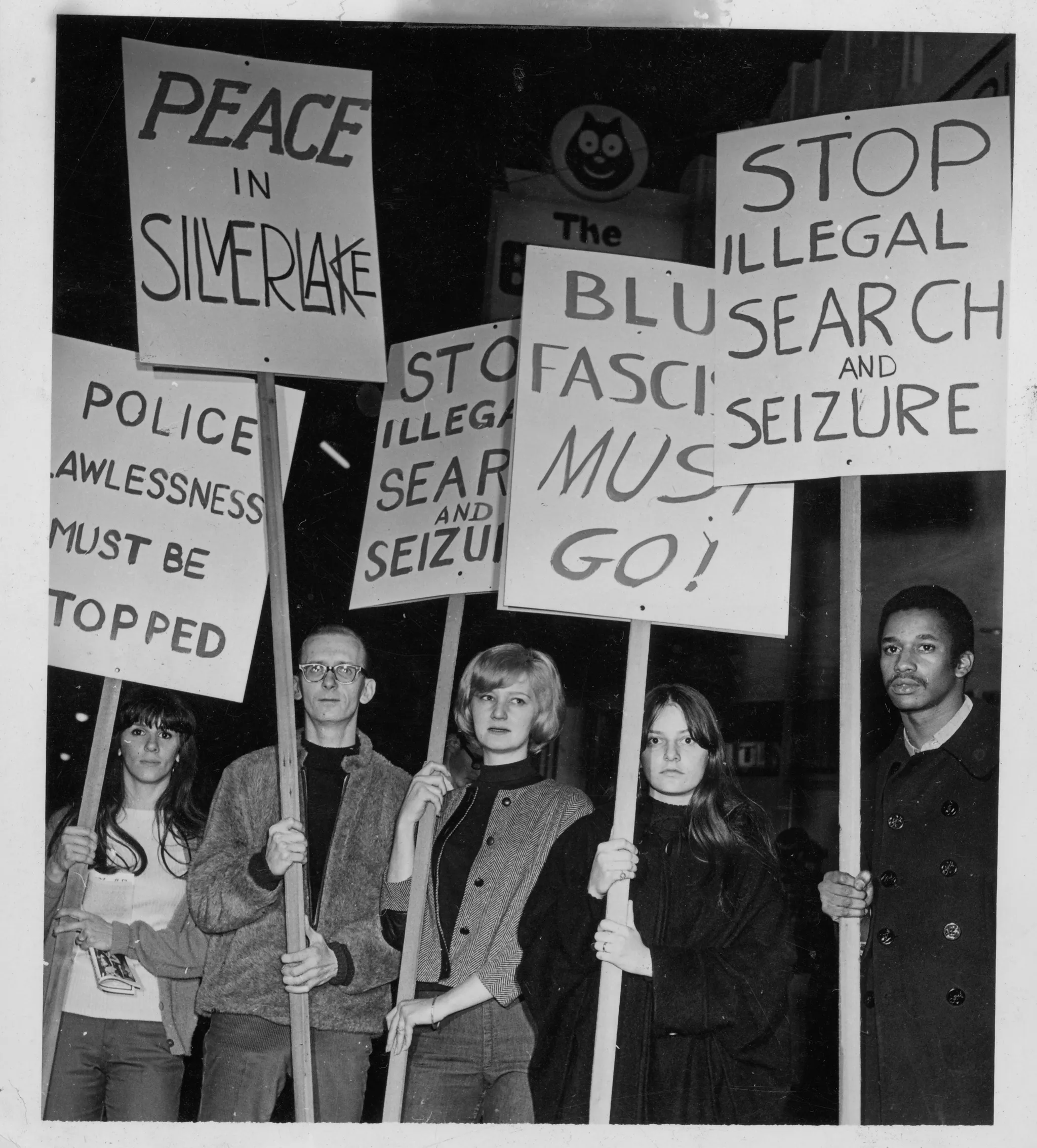

If you look at the pictures, none of the regular news media covered us. They were all from the Free Press at the time. They were the only ones that covered the demonstration. A couple of years ago, I met with [former] police chief [William J.] Bratton, and we were looking at the pictures, when I said, “Do you see anybody smiling there?” He said no. And I said, “That’s because [the protesters] were all terrified to do this, but they knew they had to.” It took place in the evening because they had jobs they would likely lose the next day.

What were the risks?

If the major news media would have covered that demonstration, their faces would have been in the newspapers, but the newspapers didn’t think it was very important because it was only those “unhappy homosexuals.” At that time, we could be put into a sanitarium for being gay. And our families could have us committed if they were embarrassed by us. There, you were subject to shock treatments and chemically castrated. We were afraid, but we couldn’t take it anymore. You couldn’t just come in, beat us up and take us to jail because we were who we were.

What was the aftermath of the protests?

Once you let the cat out of the bag, there’s no stopping it. I started an organization, Santa Monica Bay Coalition for Human Rights. In 1970, we were marching in the LA Pride parade, and we had this big banner. I was in the front, and there were mounted police officers. I was nervous, but one of them turned his horse away from all the rest and gave me a V-for-victory sign. I knew we were going to be okay.

And what was the legacy at the Black Cat?

We got the Black Cat designated as a historic landmark. There’s a plaque on the front of the building now. When I went back one time, there was a note that was attached to the plaque, and all it said was “thank you.” That was enough for everything.

Romanoff discussed the evening’s events with Time Out, and his account has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Discover Time Out original video