A 1993 donation of some 200 works by Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–89) jump-started the Guggenheim’s photography collection, so it’s only appropriate for the museum to mark the 30th anniversary of his death from AIDS with this institutional tribute. Mapplethorpe created some of the most beautiful and iconic photos (black-and-white nudes, portraits and flower studies, among them) of the 1970s and ’80s. A formal perfectionist, he was attacked by the religious right and its proxies for explicit depictions of gay sex—particularly of the S&M variety—as well as for pictures of naked children. He was also criticized from the other end of the ideological spectrum for his erotic photos of black men, which many deemed objectifying.

This exhibition, the second part of a yearlong project, contrasts 16 of Mapplethorpe’s works with nearly two dozen pieces by six queer artists from succeeding generations. They include four gay African-American men, with the work of one, Glenn Ligon, directly critiquing Mapplethorpe. In his Notes on the Margins of the Black Book (1991–93), Ligon appropriates images from The Black Book, Mapplethorpe’s 1988 volume of photos of (often naked) black men and presents them alongside framed comments, ranging from academic to anecdotal to utterly personal. Quietly devastating, Ligon’s piece is now considered to be as important as the original itself.

Envisioning the politics of race and sex more literally, Paul Mpagi Sepuya poses naked in front of the camera while using curtains and mirrors to divide and refract parts of his body. Sometimes, he’s intertwined with other (often white) figures that are similarly deconstructed. Unlike the controlling gaze of The Black Book, Sepuya takes a self-reflexive view that notes the collaboration between photographer and model.

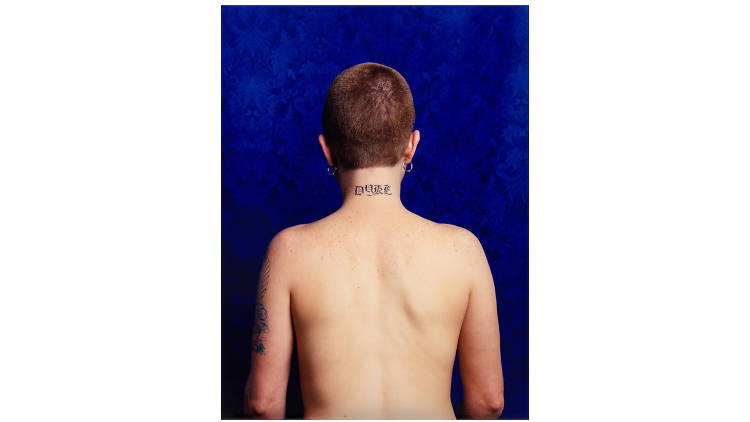

Mapplethorpe also unabashedly glamorized sexual subcultures, something Catherine Opie picks up on with her lush color print, Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993). In it, the artist presents herself from behind with a scene of stick figures cut into her back. Oozing blood, the drawing depicts two women holding hands in front of a small house—an alternative take on domesticity that’s echoed in Mapplethorpe’s Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter (1979), in which two men are seen in their staid, bourgeois living room clad in head-to-toe leather and chains.

South African artist Zanele Muholi’s 2018 self-portrait in a crown and oversize earmuffs rhymes with Mapplethorpe’s 1980 self-portrait in makeup and fur. Muholi’s confrontational self-possession—half regal, half silly—is miles away from Mapplethorpe’s coy drag, transgressive and Duchampian though it may have been. Yet that very self-regard, along with Muholi’s ability to make black skin (digitally darkened, in this case) glow with a myriad of tones, recalls Mapplethorpe’s nude portrayals of African-American men, notwithstanding their treatment as objects of desire. Dotted with such revelatory moments, this deeply intelligent exhibition lets us reevaluate Mapplethorpe’s achievement and influence, which remains as indelible as it is equivocal.