Large, ambitious retrospectives take a long time to organize, especially when linked to even bigger events like the Guggenheim’s golden anniversary celebration of the Frank Lloyd Wright building. So planning for this survey of the work of Vasily Kandinsky (1866--1944), the pioneering modernist who pushed painting into pure abstraction, began while the museum’s former director, Thomas Krens (who stepped down in 2008) was still running the joint. Yet “Kandinsky” is nothing like the flashy crowd-pleasing spectacles—“Armani,” “Art of Motorcycle”—that characterized Krens’s regime. Instead, the show hearkens back to that Mad Men year 1959, when Wright’s edifice opened and the New York art world was a smaller and more purpose-driven place. For a regular Gugg attendee like yours truly, the effect was rather like waking up again in Bedford Falls after a long, dark sojourn in Pottersville.

Yet it was Wright’s transformation of the museum into destination architecture that would ultimately encourage the curatorial excesses of the Krens era, and in this respect, it’s somewhat ironic that Wright designed the Guggenheim with Kandinsky’s curving forms in mind. That’s also the reason why this is probably the best-looking show here since the last time the Gugg mounted an comprehensive overview of the Russian painter’s work in the 1980s.

This iteration is bolstered by loans from the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Stdtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich, but Kandinsky is most closely identified with the Gugg, even though he never spent any time in New York. His work formed the core of what was once called Guggenheim’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting, a name that reflected the presumption during the first half of the 1900s that pure abstraction represented the end-all of Western art. The ironies of Pop Art and the materialistic approach of Minimalism eventually disabused that notion, but certainly Kandinsky’s canvases served as the example for American painters such as Barnett Newman, bent on being more abstract than anyone else. Just as important in this regard were Kandinky’s writings, like On the Spiritual in Art, published in 1912. Even more than Picasso, then, Kandinsky served as the bridge between European modernism and the New York School.

The Guggenheim’s association with the artist began in 1930 when Solomon R. Guggenheim, his wife, Irene, and Hilla Rebay, who would later become the museum’s first director, traveled to Germany to meet Kandinsky, who at the time was teaching at the famed Bauhaus. By then, the painter was well into his late career, a major figure in the avant-garde who’d already entertained extended stays in Paris (1906--1907), Munich (1908--1914), Moscow (1914--1921), and at the Bauhaus in both its Weimar and Dessau incarnations (1922--1930). In 1933, he followed the Bauhaus when it moved to Berlin; that same year, when it was finally shut down by the Nazis, Kandinsky returned to Paris where he spent the rest of his life.

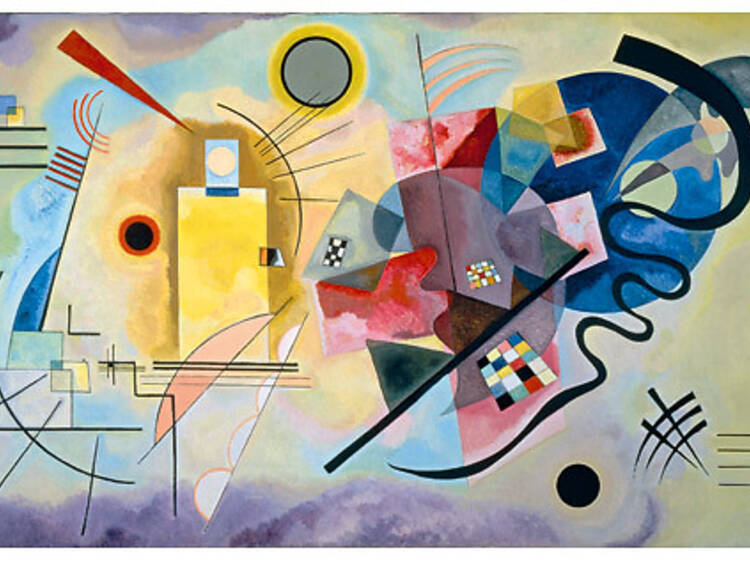

Taken as whole, his oeuvre moves inexorably from representation to what most art historians consider the first purely abstract style—or, as Kandinsky himself considered it, an art independent of one’s observations of the external world. Whether he actually achieved the same level of independence in this sense as the Abstract Expressionists, notably Newman or Jackson Pollock, is somewhat debatable. I certainly kept seeing references in his compositions to the external world—amoebas wriggling under a microscope, planets whirling through the cosmos—intentional or not. But what is undeniable is that Kandinsky’s development was informed by his peripatetic existence. During his initial period in Paris, for example, his work responded to the Postimpressionism in the air, though he also introduced folkloric elements from his native Russia. This, in turn, would evolve in Munich into the landscapelike compositions hovering on the brink of dissolution that characterized his association with Der Blaue Reiter, the publication he worked on with Franz Marc. Returning to Moscow, Kandinsky became familiar with the Constructivism of Tatlin and Rodchenko, among others; accordingly, his painting took a turn toward hard geometry, a trend that was only reinforced by his subsequent experience at the Bauhaus.

Throughout it all, Kandinsky fulfilled the role he posited for the artist: a metaphysical prophet ushering in the realities of tomorrow. That faith in the future may be long gone, but what matters is that Kandinsky’s achievement continues to resonate for us today.