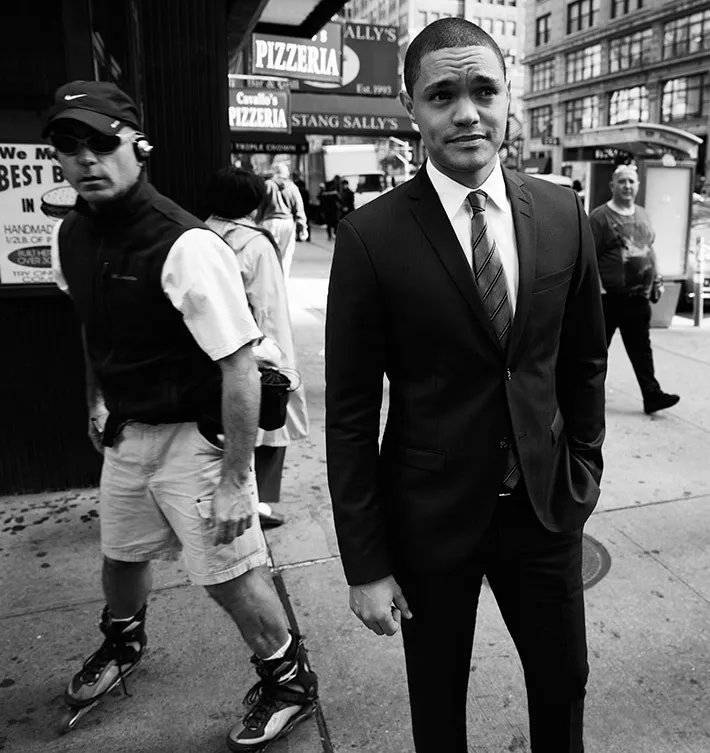

"Trevor Noooah!” That’s the first thing I hear when I arrive at our on-the-street photo shoot. The yelp came from one of two blushing teenage boys who’d spied The Daily Show with Trevor Noah host across the street. Then, a minute after they pulled their caps down and sank into the Friday morning pedestrian traffic along Seventh Avenue, a thirtysomething brunet chirps, “You’re killing it!” Others approach with phones in hand, asking for selfies. Trevor Noah, it appears, has arrived.

RECOMMENDED: See all New York Comedy Festival coverage.

While the South African–born comic has steadily garnered attention as a stand-up over the years—he headlines the Town Hall as part of the New York Comedy Festival on Saturday 14, and his Comedy Central special Trevor Noah: Lost in Translation premieres on November 22—nothing presaged the surge of attention heaped on him after the March 2015 announcement that he would succeed comic-in-chief Jon Stewart. Noah, whose father is Swiss-German and mother is Xhosa, created a name for himself in his mother country, which had basically a nonexistent comedy scene compared with his new home of New York. He played one international festival, then another, was endorsed by Eddie Izzard and toured the States with Gabriel “Fluffy” Iglesias. He then landed this plum gig after less than a season as a correspondent, with Stewart’s seal of approval, after the likes of Amy Schumer and Chris Rock passed on the job.

In a few short months, the 31-year-old has endured the skepticism of the uninformed—Trevor who?—and the barbs of those who found his questionable three-plus-year-old tweets about Jews and women as grounds for dismissal before he’d even sat behind the desk. (A sample of what caused the shit storm: “‘Oh yeah, the weekend. People are gonna get drunk and think that I’m sexy!’—fat chicks everywhere.”) As for Comedy Central, the brass are hoping Noah can carry the torch for one of the two shows (the other being South Park) that made the network what it is. It’s a lot of pressure. Yet Noah remains a calm presence in the eye of the storm. Once we hop into a car heading up the West Side Highway to The Daily Show offices, Noah settles into his seat and answers each question from a thoughtful remove. Not bad for a guy who, at the time of our conversation, had been on the job for only two weeks.

Given you’ve taped just eight shows thus far, how do you feel?

It’s overwhelming at times, but often I’m so engulfed in the work that I don’t have time to get caught up in my own head. It’s that old adage of, When climbing a mountain, just look at the step ahead of you. Every now and again, you’ll stop and look out and see how high you’ve come, maybe take a glance up to the top to see how far you have to go. But it’s about grinding through it and enjoying it as you go.

What are the moments when you’ve felt things were really clicking?

Every little joke that works, every little point in an argument that hits—all of those I take. I make note of the ones that don’t work as well, but it’s about acknowledging small progress. If you try to lose weight, but you’re weighing yourself every day, you’re going to get very frustrated. You need to look at the broader aspects: Okay, today I ran a bit farther, worked out a bit harder, lifted a bit more weight. And if you work on the process, the end result will be: I have a good body or, in this case, a good show.

How close did you come to feeling ready to host the show before you started?

I don’t think you’re ever fully ready. At some point you just have to jump in and do it. You just have to let it evolve onscreen, on air—which is risky, but it’s fun.

How did you feel on the day of your first show?

You are so busy. You have no time to feel. In a moment, you think you’re going to be nervous, and then you realize you have work to do. In a moment, you think you’re excited; you have work to do. So you try to find those moments so you can at least savor what’s happening around you, but it really flies by so quickly. You do the show; you’ve done the show. And then you can’t even spend time enjoying it, because it’s a Monday. There are no celebratory drinks; there’s no party afterward. It’s, Let’s get ready for Tuesday. And Tuesday, it’s, Let’s get ready for Wednesday. And so on and so on.

How did Jon Stewart do it for 16 years?

He was insane. And I realize this now. There’s something very wrong with that man.

What was Jon’s advice?

“Make your show the best show that you feel needs to be made.” And that was it. I think Jon is very careful in that he doesn’t want me to make his show or the show he thinks I should make.

Stewart’s name is synonymous with The Daily Show and its format, but you’ve kept the show intact, down to the theme song. Why not radically change it?

It’s the same reason Apple doesn’t change the iPhone: Because they know it works. So all you do is look to add what you would feel would be an improvement to the product. At some point, I could argue, the changes in the iPhone are not particularly needed. But in using it, it becomes intuitive, and you think, This makes sense, I don’t know why we weren’t doing this before. That’s how I feel about the show. If you know you don’t have enough time to completely revamp and re-create an entire show, why throw away something that works? Why not build on that fantastic platform and know that you have the time to evolve?

Looking back, what is the thing no one could have prepared you for?

The sheer difficulty of bringing to life what you’ve spent the whole day putting together on the page. You spend the whole day as a practical journalist slash comedy writer slash creative, and then at night, you have to switch to entertainer. No one could have prepared me for that fully—getting into that zone and letting go. It’s difficult to say, This is it, I’ve put the work in and done everything I can do, and now I just have to let go and enjoy it.

On one of your first days on the job, the shooting at Umpqua Community College in Oregon happened. You were thrown into the gun-control debate pretty quickly.

The gun-control thing is weird to me. Sometimes we get so caught up in the face value of phrases and can’t think around them. So you say “Black lives matter”—immediately some people hear, “I hate the police” or “Black lives are the only ones that matter.” With gun control, some people hear, “Take away all guns” or “No right to bear arms.” Some people say, “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” And I agree with that. So maybe it shouldn’t be “gun control,” it should be “gun-owner control.” Because we don’t need to control guns, we need to control the people who own guns. Or control who gets to own guns.

What was your reaction when bloggers resurfaced your controversial tweets when you were announced as the new host?

You go through a range of emotions. First, you’re frustrated. There’s a little bit of disbelief about what people are trying to do or the manner in which they’re trying to do it. Then I very quickly found my place of calm and peace. But it was the same thing as when I had to change from preschool and kindergarten to what we call primary school. I lost my shit. I was like, This is ridiculous. I have to wear different clothes? Why is there no more nap time? I hate this more than anything in the world. And then one day, you just go, This is great. I don’t know why I was so stressed.

“Jon Stewart was insane. There’s something very wrong with that man.”

Photograph: Jake Chessum

Photograph: Jake Chessum

Has the way you look at Twitter changed?

That is one of the most frustratingly illogical questions I get asked. Because if you have to go back many years and ask me to change from who I was, you may as well say to me, “You used to pee your pants when you were five. I hope you know you can’t do that anymore.” I say, “Yes, that’s why I don’t do that anymore.” So they went back to when I was younger, and now they’re asking me to change—but the change has already happened. “Well, are you going to apologize for peeing in your pants?” Well, no, because when I was five, I peed in my pants. I don’t pee in my pants now. And I haven’t peed in my pants for a very long time.

I’m wondering how you use Twitter as a tool.

I evolved with Twitter, as did a lot of other comedians. Look at Louis C.K. He quit Twitter because he had issues with it. He said, I don’t like this medium. I don’t want to write jokes here, because I burn them, and if I promote shows, people complain about that. So he quit. Michael Che from SNL, same thing for him. He was like, I’m making jokes, and people said, You’re this, you’re that. And he said, This is not the forum, clearly—and so, he quit. So you have to choose. Do you accept the evolution of it, or do you just quit?

Beyond just coming at The Daily Show from a different angle, what are the advantages of being something of an outsider to the culture?

Not being weighed down by conversations that may have been had previously in and around a problem. I haven’t grown up as a Democrat or as a Republican, so I get to pierce the partisanship that surrounds most of the questions. Sometimes in the room, I will have a disagreement with the writers or other people, and I’ll say, “I don’t agree with that.” And they go, “But you have to agree with it.” And I say, “Why?” “Because that’s a conservative thing you’re saying.” And I go, “Well, I’ve learned something new about myself today. That’s a view held by Republicans.” Because where I came from, we didn’t have that. There is no party that speaks to you if you’re rich or if you’re poor, conservative or liberal. You can’t just say, “That part is aligned to these people.”

You’ve done a lot of touring around the U.S. How much has it helped you understand the tastes of the American audience?

I learned a huge amount. You start to realize there are more things we have in common than we think we do, and there is a broader discussion we can have. And you need to keep doing that to keep moving. Because that’s what I feel happens: People live in one place, so they think in one way. And they say, Who are those idiots on the other side? And they don’t realize what they’re doing is really looking at a bizarro version of themselves. It helps to spend some time in the world of the person you think is wrong, because then you start to realize they’re coming from the exact same place as you are.

You were born in South Africa during apartheid, which you talk about onstage. What did you learn about the social dynamics of race in the U.S. while performing here?

It was the same everywhere in the U.S.— the same as it is in South Africa. We share a common narrative of racial discrimination and some form of slavery and class system, so the remnants of that are still visible in many places, in varying degrees. But you can feel it everywhere, wherever you go in what was once touched by the British Empire.

What were your thoughts about New York before you got here?

When you first come, it’s the fascination of this magical movie and TV world coming to life—Times Square, the subway, all of the bridges over the rivers. It doesn’t disappoint. That’s the great thing about New York: No one can come here and go, Uh, yeah, it was just what I thought. It will always blow your mind, every single time. And then, when you live here, you start to enjoy the serenity that you find in the familiar places that you frequent. When you scratch below the surface, you start finding some really wonderful and interesting places, people and activities that completely change what you think New York is all about.

You’re a handsome and assured guy, yet when you had the founder of the dating app Bumble on your show, you shyly let on that you might need help meeting people. How much trouble do you have, really?

I have never suffered from an enlarged ego. The possibility of being rejected is one that is constantly looming above all of us. And so I’ve never unnecessarily delved into the realms in which I may be unnecessarily hurt. I’m not the kind of guy who just runs up to random people in bars or clubs or any environment, to be honest. I meet most people through other people.

And if someone were to buy you a drink?

I don’t drink. I’m trying to learn how to drink wine, because I hear it enhances your food. So, maybe?

How much of a break do you get on weekends?

This weekend I’m at Politicon in L.A., doing a set and a little Q&A. Next weekend, Eddie Murphy is being honored with the Mark Twain Prize, and I’m going to watch Jon Stewart do stand-up. That’s the ultimate irony in my world, in that now he’s the free man doing stand-up comedy, and I’m the guy working and coming to watch his show.

How much of your brain have you been able to reserve to think about stand-up?

It’s not my brain that I need to reserve; it’s my time. This was a surprising discovery for me: Stand-up is where I rest. When I’m onstage, I relax, I calm down, and I think freely. Stand-up is like yoga for me: It’s a beautiful space to exist in. I explore; I find magical moments. I can be as wrong as I want to be or as right as I need to be. I enjoy that freedom. On a TV show, you’ll never have that full freedom.

How is your material coming along for your New York Comedy Festival show?

I have less stage time than I have material, which is a good place to be in. I’m constantly working stuff. I just press pause, really, and go do other work and then pick up where I left off and carry on with the material and the shows. And then I do it again and I do it again and I do it again. And so for that show, I’m as ready as I’ll ever be.

When I last interviewed you, you said South Africa had one club. What’s it like to wake up in NYC, where there are so many?

It’s a wonderful place to be. You get to go in, go out, prepare, change, amend, conclude. You have a much more accelerated growth rate when it comes to creating material. You just get to do it so much, in front of so many different people. If you have an idea in your head, you can figure it out. Really quickly.

So you’re happy here, being a comedian?

New York is the home of comedy on this side of the world.