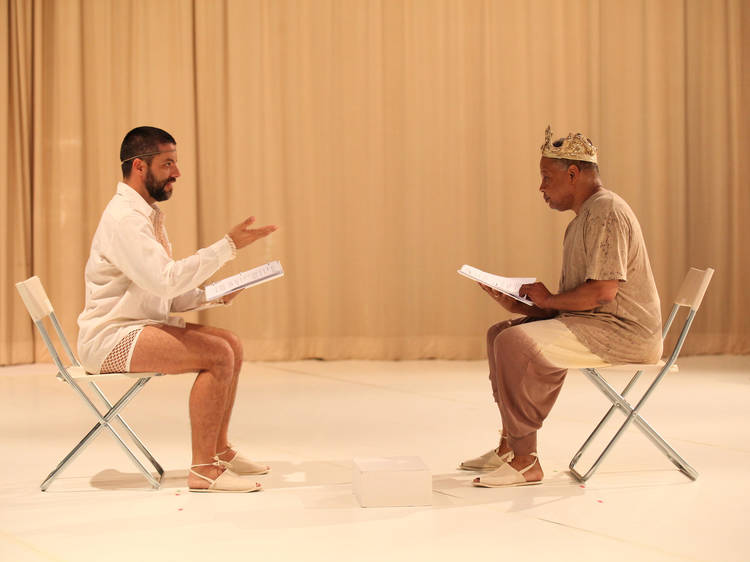

In Miguel Gutierrez's newest dance, two legendary improvisers, K.J. Holmes and Ishmael Houston-Jones join the cast at the BAM Fisher December 4 through 8. In advance of Miguel Gutierrez's New York premiere of And lose the name of action, K.J. Holmes and Ishmael Houston-Jones talk about their experiences dancing in another choreographer's work and the creative process, which even included a ghost hunt.

In And lose the name of action, Miguel Gutierrez is inspired by neurological conditions, but he also has something else on his mind: casting. After realizing that he’s consistently made dances featuring performers around his age or younger, he decided to switch things up. “I wanted to work with some people that were older than me,” he says. In his new piece, which is at the BAM Fisher beginning December 4, Gutierrez showcases Michelle Boulé, Hilary Clark and Luke George, along with two prized New York improvisers: K.J. Holmes, who turns 57 during the run, and Ishmael Houston-Jones, 61. How often do you get to go hunting for ghosts in a graveyard? Recently, they spoke about the year-and-a-half process.

Time Out New York: What was your reaction when Miguel asked you to do this?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Why? [Laughs] Did you ask why?

K.J. Holmes: It was interesting, because he had asked me to work with him privately on some Body-Mind Centering as a way to research the neurological system, which is one of the themes of the work. He invited me to come to a rehearsal as a way to see if I wanted to be in the piece, and I think it had to do with extending that conversation.

Time Out New York: Who was he working with?

K.J. Holmes: It was Luke George and me. Miguel had us dance as if we were being controlled by an alien—or something outside of the usual senses—and to remove all emotionality. In some ways, we’re not really dealing with that now. It was leaving behind a usual way of improvising and going into a very altered state. I loved it. It was fascinating. And then he seemed to feel that it worked, so then he invited me to be part of it. The interesting thing is that I’ve been thinking about not dancing so much because I’m studying acting. Somebody asked me, “If you were going to work with anyone other than doing your own work, who would it be?” And I said, “Miguel, but that probably will never happen.” And then he asked me, and I thought, That is so amazing. I love his work, and we have been engaged in a dialogue through teaching. I didn’t really question why, because I understood it having been in the process with him a little bit. It made sense. And then to know that you might do it and that the cast was so diverse, it seemed incredible. I didn’t know what was going to happen—what he was going to bring from all of us.

Time Out New York: So why did you end up saying yes? Was it a matter of why not?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I thought, Why not? Also, I haven’t been making that much work of my own. I’ve been focusing on revivals, and I like his work a lot. I thought it would be good for me to work with someone who comes from the same general world, but works very differently than I do. I thought it would be good for my own growth.

Time Out New York: Going back to that studio experience, what was so rewarding about improvising in an altered state?

K.J. Holmes: It’s similar to what Ishmael was saying about growing. I have felt that I have a certain style or way of improvising that I stay within and to be asked to do something outside of my range is wonderful. And to invite other parts of myself in, so it’s not so much like I’m just going into an unfamiliar state outside of myself. It is really bringing more of myself into it—the whole process has felt like that in many ways.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: A lot of the piece stems from his investigation and research into the brain and consciousness, so much of the improvising has been, not about that, but sparked by it. We did a lot of work with senses, and really breaking down the primary senses into the more esoteric senses. Instead of just improvising on the whole self, we focused on tiny aspects—like really seeing if you could home in on smell.

K.J. Holmes: It feels really remarkable to let somebody else make certain decisions as well; I’ve been invited to enter into these different states, but it’s really toward his vision, which I trust. I’m happy to give myself to his editing and compositional ideas.

Time Out New York: Is it a comfortable situation for you?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Usually. [Laughs] Not always.

K.J. Holmes: It’s hard sometimes to let go of some things that you get attached to, but it also is interesting: What’s the bigger picture? What is this piece going to be? Now that we know what the piece is, how is it to perform it? That’s a whole other journey of understanding.

Time Out New York: Has it changed much since your first performance?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Not really. The form is definitely the same. It’s very contingent on space, which is a big part of it, and in the two spaces we’ve performed it already—the Walker and in Norway—were very different. The basic score of the piece has stayed pretty much the same since the opening at the Walker.

K.J. Holmes: I think, too, that having an audience shifts us. The audience is always a very big part of performing, but we engage with the audience very directly in the piece. [Laughs] I can’t say more than that.

Time Out New York: I know Miguel has some surprises planned.

K.J. Holmes: Yeah. It just feels that this piece has held an adjustment to having people there and that has led to a very different momentum. Oh, okay, people are here and something else is starting to coalesce about what it might be about.

Time Out New York: What has he asked you to do in preparation?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I’m not a big rehearsal person in my own work. And when we’re together—of course it’s concentrated time. There are weeks when we’re together and then we don’t see each other for months. We’ve been having six-hour rehearsals and really focusing on material in a specific way. A lot has been on vocal work, because there is singing and acting in the piece. Concentrating on different entry points for improvisation. Listening to video-lectures on the brain. It’s been like, “Today, we’re going to watch a lecture about this woman talking about how the brain works in cognition.”

K.J. Holmes: He took us through different states of different senses. We worked on more esoteric senses. He videotaped our improvisations and chose different sections to learn and then put different parts together.

Time Out New York: Can you give me a sense of what it was like to go beyond the five senses?

K.J. Holmes: So there are the usual senses; we went into the sense of emotion and performance and play—a sense of risk, time, space. There were 20.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: And kinesthetic awareness.

K.J. Holmes: So senses that are about you inside of your body and then what goes on past your body—more and more into space and relationship, into almost being influenced by what’s not there. Giving yourself over to your imagination.

Time Out New York: How difficult was that?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It’s fun. I’m an improviser so this was a fun score to have.

K.J. Holmes: Again, it was being led beyond my own experience. And some of it is familiar, but again being directed and led through it and talked through it—and with these other people, what starts to collide or what starts to harmonize and our differences are becoming more distinct as well as when we’re merging into similar places and states.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: We had a couple of one-on-one sessions after our first group residency at MANCC [Maggie Allesee National Center for Choreography], and he had me dancing as if I were dancing with a ghost. At MANCC, we went on a ghost-hunting trip, which we can talk about endlessly. [Laughs] But I did this dance, and he chose maybe a two- or three-minute section of it and then other people had to learn it. I couldn’t learn it—because I don’t learn set choreography.

Time Out New York: You always say that. Is it really true?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It’s very true.

K.J. Holmes: But he is, he is.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: But very little. That dance I couldn’t learn and in the end it’s become a duet for Michelle and Luke.

K.J. Holmes: I’ve lost track of the material that we set: I don’t even know the source anymore, because it’s become something of itself now. But it does hold the experience, for sure.

Time Out New York: Why don’t you perform choreography?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Because I’m not good at it. I’ve never been good at it ever. I was always at the back of the line in modern classes, and then I just became not interested in it.

K.J. Holmes: I do set material, but I am an improviser. And I feel like it was a choice. Being exposed to improvisational forms and somatic forms in the ’80s seemed more like a decision to not do other things, but to focus on improvisation. Even being in this piece and being with these other dancers, there’s more of a blend of techniques. I wanted to improvise instead of doing choreography.

Time Out New York: You were rejecting set choreography?

K.J. Holmes: In a way, definitely. I’ve always felt that in doing more technical dance, which I did for a long time growing up and then in my early twenties, I was wearing a form. Improvising led me into feeling that I was doing the dancing. Another reason I like working with Miguel is that I’m putting on my own form through learning my own movement from a video. I’m wearing myself and other people. I actually really love being pushed beyond my own form.

Time Out New York: Is the piece mainly set material?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: In balance, I think there’s more set material than improvisation, but there’s a large improvisation section as well. I do have to learn some set material.

K.J. Holmes: Miguel is asking for a lot of precision. I think the one thing I’m learning the most is that I’ve based a lot of my work on sensation and oftentimes where I think I am is not where I should be. I don’t look in the mirror usually, so it’s really about that kind of, “No it’s not here, it’s there,” and it makes a difference in terms of what we’re trying to do—being together or not being together. The more that we can be precisely together makes a big difference.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It’s an interesting task for me. It’s growth. It’s like, Okay, I have to end this section, and I have to be exactly with everyone else and not off.

K.J. Holmes: I did something in the last performance in Norway, which is an improvisational thing, and I realized it’s not going to work in this piece. At the very end, I have a duet with Luke George, and I have to hold a balance and then start to move. I fell out of the balance. I did this improvisational thing where I tried to make it look like I followed it rather than sticking with the choreography and I realized, I can’t do that. Even if you lose your place, you have to come back to that place, and the chops of improvising—where mistakes happen and you follow them so they become a new way of developing material—don’t work.

Time Out New York: So you’re going against instinct in a way?

K.J. Holmes: In a way, which I also really like. I’m developing a new piece now. I’m an artist-in-residence at Movement Research and it’s interesting to feel myself going into my own work after working on this. I don’t know exactly what’s happening, but something new is wanting to appear in my own work as well, and I don’t know if it’s me wanting to be precise in a different way or to replicate something? I do feel something is different.

Time Out New York: So what happened with the ghosts?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Miguel said, “I’m interested in the supernatural and the paranormal,” and they found these ladies who run Big Bend Ghost Trackers. We went on a five-hour ghost hunt in Monticello, Florida, which is the most haunted small town in Florida, apparently…

K.J. Holmes: Because of the Civil War.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: So they took us to an abandoned jail and an abandoned school and, finally, at midnight, we ended up at a graveyard. Some people had these dowsing rods—these sort of divining rods—that were supposed to cross when the ghost was there. Some of us had little Radio Shack transmitters. [Laughs] I’m like the most skeptical person in the world. But we were wandering around looking for ghosts, and that has found its way into the piece.

Time Out New York: How skeptical were you about ghost hunting?

K.J. Holmes: I kind of believed it. I don’t doubt that there are ghosts and things outside of our understanding…

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I don’t doubt that. I doubt these ladies. [Laughs]

K.J. Holmes: Oh, the ladies. But even in the graveyard, I had a couple of experiences that were very powerful of feeling presence based on these little devices that were steering us.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I got nothing. [Howls with laughter]

K.J. Holmes: The skepticism gets in your way! I think I would have been afraid to go into a graveyard at midnight in another situation, but it opened up my interest—the safety of inviting things that are behind our control.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: We said the Lord’s Prayer before we went in. In a circle. [Laughs] Seriously. It was something about the way that they dealt with the ghosts. There’s a Civil War Confederate person in the graveyard, and at one point they were yelling, “Come on out! Come on out!” I was like, Oh…I don’t think so.

Time Out New York: It just sounds fantastic.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It was wonderful. I am a believer in things we cannot see and things that are beyond ourselves, it’s just their take—also, Miguel and I had a little political issue with them. They kept saying, “After the unfortunate conclusion of the Civil War…,” and we were like, “You mean the end of slavery? That?” They said it more than once.

K.J. Holmes: But that was the first time of us all meeting together, so it was an interesting beginning to what we were about to embark on.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: And I think it influenced the music, actually. [Composer] Neil Medlyn picked up some ideas about that, and Miguel wrote a song. I’m not a singer at all, so that has also been really good for me. That’s another idea of precision that I don’t have. I have been developing it. And getting better.

K.J. Holmes: And that’s another skill of Miguel’s: He can hear and lead you to where you need to be.

Time Out New York: I’m so curious to see this piece.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Gerri Houlihan [of Florida State University and the American Dance Festival School] said it’s very different from a Miguel piece. I think it’s a transitional piece, and I think it’s the first time that he’s worked with entrances and exits, which I didn’t realize until we were doing it. In all of his other group pieces, dancers were onstage the whole time; in this one, there are multiple entrances and exits.

K.J. Holmes: It makes sense with the idea of what’s visible and what’s not visible.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: And he’s also working with video technology in a different way with Boru [O’Brien O’Connell]. It’s a large part of the piece. It’s shot on black-and-white film, and it’s really beautiful and simple. I don’t think it overpowers.

Time Out New York: There is also text. What can you reveal about that?

K.J. Holmes: It’s a dialogue between a philosopher and a student that Boru modernized. And Miguel also added things to that; it’s not verbatim.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It deals with, what is being? How do we know things? Are things real because we experience them? Do things exist only in the mind?

Time Out New York: How do you fit in with the younger generation in the piece?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: They’re not that young. I think 33 is the youngest.

K.J. Holmes: It’s not so much about age as the different experiences that we’ve all had. It hasn’t felt like we’re the older dancers. We’re different generations within the piece, based on our states and our qualities and our characters.

Time Out New York: Did you do anything different trainingwise outside of the process?

K.J. Holmes: I just do what I do. I do yoga and I swim. I don’t take dance classes. I actually feel very good in my body as a dancer, and I don’t feel I’m trying to keep up for the most part.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I’m just trying to stay in shape. I’m older. I am. I wish people would start believing me.

K.J. Holmes: That’s where we differ. I don’t think he’s old.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I’m so old. I think it’s great that people don’t think of me as older, but my body is different from 33-year-old bodies, really. Aerobically, I’m training. I’ve been doing weight training. The boring stuff, like crunches and push-ups.

K.J. Holmes: You are?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Yeah! Because I have to make it through. That opening solo is just so hard for me to get through. I always feel like I’m going to throw up by the end of it. Think of your father out there doing this. It’s very interesting—it doesn’t happen so much now but it used to happen at Governors Island because we usually had an hour of everyone warming up themselves. And everybody has their own private thing. One day, everyone had their iPads or laptops open to different warm-ups, and they were all listening. It was the most bizarre thing—yoga or Feldenkrais. Everybody in the room was silent and plugged in like a weird Apple commercial, and I’m just lying on the floor breathing. It’s what I can do in the morning.

K.J. Holmes: I would say that I’m learning a lot from them in terms of how to combine different techniques. I work with Michelle sometimes. Everybody gives each other advice and ideas along the way. Everyone in the group knows a lot about the body and how to train and to keep yourself injury-free and, if there is an injury what do you do? There’s a lot of knowledge in the room. That’s particular to this group that Miguel organized. I think he’s bringing out each person in a different way, even in terms of the dancing.

Time Out New York: How so?

K.J. Holmes: Different dynamics. Hilary’s dance is really different than Michelle’s. They’re very different performers, and there are beautiful qualities there that are essential to the piece because they’re in it. The solo Ishmael does that’s very particular to him—

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It’s improvised, but it’s a very specific improvisation where I have very specific tasks. So it’s not just me improvising any way I want to. There is a real clear idea about what I’m doing, and I often ask Miguel to repeat it to me beforehand so I don’t lose that focus.

Time Out New York: What is he bringing out of you?

K.J. Holmes: One thing is being able to work with text more. I did an acting training for two years at the William Esper Studio, and I am really interested in looking at the relationship between language and the body. Movement and words. And I am being used in that way. I think, in terms of the dance work, there’s a certain way of partnering—but it’s a partnering that has to do with understanding the timing of the set material that was improvised. Not just following the sensation, but the replication and the musicality of something that is about the relationship and the partnering. And the emotional dynamics that occur again and again based on a relationship. I have a duet with Luke that I feel really is emotional because of where it is in the piece and what’s happened before it. Now I see the chronology.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: The opening duet is for Miguel and me. It’s about being precisely together, which is actually really hard because we’re mirroring each other and our bodies are really different; we make these minute adjustments so that they match. It’s about finding the precision and emotionality and focus. I have a tendency not to look at him when I’m doing it. I tend to not look at people when I’m doing contact; it’s about touching and feeling and not using your eyes. He really wants that kind of focus, and I realize that’s why I’m not used to looking people directly in the eyes when I’m dancing. So that duet is challenging. I feel like I’m getting it. But sometimes I feel I have to really work at getting it.

Time Out New York: What is the history between the two of you?

K.J. Holmes: I met Ishmael in Vermont in 1981. It was the first time I ever did an improvisational workshop. I was about to stop dancing, and I went to this workshop as a final thing before going back to school and I fell in love with improvising. It was in Putney, Vermont, and it was a huge experience of people exploring what does it mean to move from the body? And the mechanics of the body. Everybody was trying to figure it out. And it was on a farm in Vermont. The studio was a barn and there were cows and a pond and we ate meals together. It was very communal and Ishmael was there.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: When I first came to New York, I performed with Danny Lepkoff. He was one of the teachers there. We were all around P.S. 122, Danspace—the world around here.

K.J. Holmes: I worked for a long time with Lisa Nelson, a beautiful improviser who had a group called Image Lab, and Ishmael was a guest once. And we improvised a lot at Open Movement at P.S. 122. And maybe Hothouse. But this is the first time officially in someone else’s work.

Time Out New York: Which pieces of Miguel’s have you been struck by?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: Enter the seen, which was the first one I saw at his loft in Bushwick. The one at the Kitchen with all the junk: dAMNATION rOAD. I’ve seen most things. The solos I like a lot. Retrospective Exhibitionist and Difficult Bodies I liked seeing together. I have never done [Gutierrez’s “absurdist workout for the radical in all of us”] DEEP AEROBICS. Have you?

K.J. Holmes: I have. It’s so much fun to just go and put on makeup and wear wild costumes and dance and everybody’s sweating—it’s a real raising-the-spirit kind of experience. I’ve seen mostly everything, and I’ve loved everything because it’s so different. Miguel creates imaginative worlds. The body is so vital, but it’s also that the world that surrounds the body is always amazing. Even the loft space for enter the seen—the drawings on the wall and how the sound was coming from outside. That’s the first time I ever saw Michelle Boulé dance, too. I was like, Who is this creature? Amazing. And dAMNATION rOAD: How far can you go to create a theater piece? I saw Last Meadow a couple of times, and the last time I saw it I almost threw myself on the stage. When they came out and were yelling at the audience, I started yelling back. I stood up in my seat. I’ve never had that happen at a dance performance.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I felt so sad after that piece. It was so weird. I told Miguel that. I had to leave. I felt really drained and sad by it. Everyone, I find problematic, because I think it has too many endings. I saw it at Abrons and once the curtain comes up, it’s such a beautiful thing. And then it keeps going.

Time Out New York: So you’ve admired Miguel’s work for years and now you’re in it. What is that experience like for each of you?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It’s different than I would have expected, somehow, and I’m not sure how. He’s much more precise and there’s more focus than I would have thought. Just knowing him, he’s much more freewheeling and everything goes. In the rehearsal process, he knows exactly what he wants and even when he doesn’t, he’s very sharp and clear about what he wants to try to get to. He’s sort of a taskmaster.

K.J. Holmes: It’s been challenging in ways that I’ve really enjoyed. I’ve been confronted by my own limitations in terms of ease and what is difficult—what I put in my own way. You are invited to use your own blocks as a way to further the piece. That was a surprise: I would encounter parts of myself that were somewhat limiting me. It’s been a great adventure. Not knowing. Not having to make the decisions. I’ve grown to understand Miguel’s ability to go for what he wants. As a performer, I’m so happy to give to that.

Miguel Gutierrez and the Powerful People are at the BAM Fisher Dec 4–8.