Even though Myanmar and Thailand share a border, politics has kept one of Myanmar’s most daring artists from stepping into Bangkok. Htein Lin, a student activist, former political prisoner and contemporary visionary, cannot attend his first solo show at West Eden, but his presence is felt in every brushstroke.

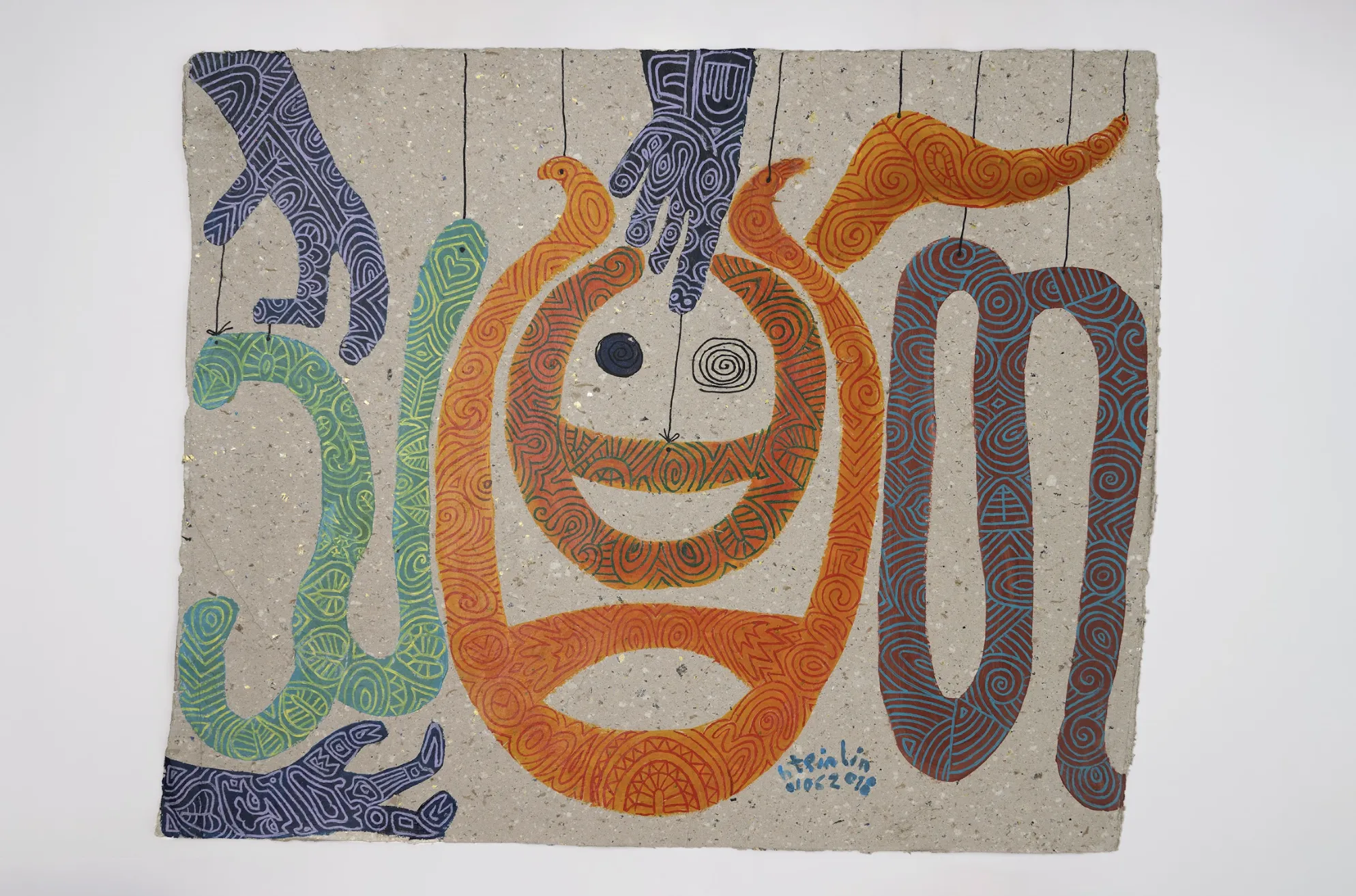

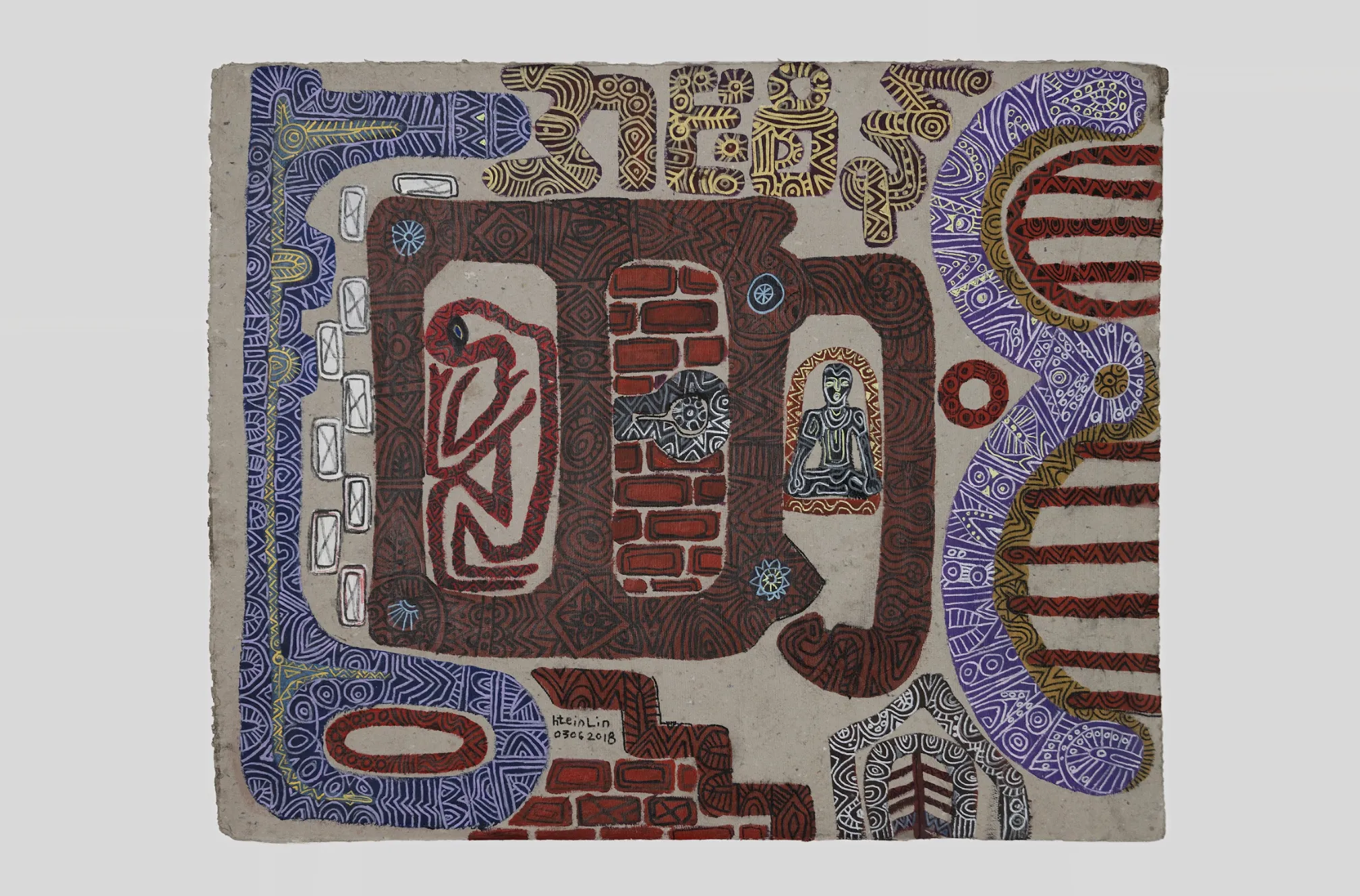

Running until October 12, the exhibition, အက္ခရာ (Ek Kha Ya), Burmese for ‘alphabet’, turns each character into a vessel of memory, resistance and identity. Through words and places tied to grief, resilience and national upheaval, Htein Lin transforms language itself into art.

In conversation with Htein Lin from Shan State and gallerist Jeen Snidvongs in Bangkok, we uncover the stories, struggles and vision behind works that defy borders and censorship alike.

When absence speaks

Htein Lin’s absence from the West Eden exhibition is not a choice, but a circumstance woven into the very fabric of his life and art. As he explains, ‘This isn't my first time experiencing something like this.’ His career defies a succession of missed connections, with political winds keeping him from international art festivals and solo shows. In both 2024 and 2025 alone, he has had to forgo major events from Birmingham to Berlin. Yet, as he notes, ‘This West Eden show is in a neighbouring country, which makes me want to be there even more.’

Technology bridges the gap. His wife or daughter stands in for him, a flickering screen acting as a window into the gallery. Visitors see the works, but he sees them too: the reactions, the awe, the connections that form across borders. ‘I feel like I am right there with them, especially in the paintings on display,’ he says, as if his presence lingers in every brushstroke.

For Htein Lin, every painting is a fragment of a story, a life intertwined with the social and political currents of Myanmar. Outsiders call his work political, but for him, it is personal. ‘My personal story is inseparable from the society I’m a part of,’ he explains. Each piece is a tapestry of lived experience, cultural memory and the universality of human emotion.

Even venues cannot define his art. He recalls a one-day exhibition in a prison cell, shared with 45 fellow inmates. For Htein Lin, the stage, grand or humble, is secondary. ‘The art itself is the heart of the matter and the people who come to witness it are the soul,’ he insists.

Material as Memory

Material matters. After his release from prison, Htein Lin discovered recycled paper – worn, textured, imperfect. It became more than a canvas as it turned into a mirror of his life. ‘The papers felt a lot like my life at the time, something I had been through,’ he reflects. Through them, he was returning to society, transformed and renewed.

In 2013, he began weaving words into his work – words of political urgency, social significance and personal resonance. Anchored in the Burmese alphabet, the text preserves identity in an era of digital homogenisation. Names such as ‘Rohingya’ and ‘president’ appear alongside intimate reflections, linking the political to the personal in a way only he can.

Censorship as catalyst

Censorship has followed him like a shadow, shaping and constraining his work. Paintings have been banned, destroyed or altered. Yet, paradoxically, this oppression sharpened his artistry. ‘I often felt the freest in prison,’ he admits. There, without the fear of censorship, his work became raw, fearless and unrestrained. The strictest boundaries forced him to layer meaning, develop subtle metaphors and create art that resonates far beyond the surface.

‘Strict censorship made me a better artist,’ he says. ‘It forced me to be cleverer, more complex and more meaningful.’ For Htein Lin, creative freedom isn’t a gift. It’s a right to be claimed, fought for and wielded in the face of adversity.

The gallerist’s perspective: a safe harbour

West Eden’s gallery owner, Jeen Snidvongs, sees Htein Lin not only as an artist but as a testament to resilience. ‘Art was his escape during his long years in prison,’ he says, ‘and it became a beacon for everyone around him.’

Jeen emphasises the gallery’s role: not to interpret, but to provide a space where viewers can experience the art on their own terms. ‘We try not to interpret works on the audience’s behalf,’ he says. ‘The exhibition carries a luminous message: be true to your spirit and it will guide you through the darkest times.’

Southeast Asian Art in the Global Spotlight

Jeen also sees the rising prominence of Southeast Asian art. Long dismissed as ‘emerging’ or ‘exotic,’ it is now commanding global attention. Its strength lies in a combination of cultural depth, resilience and continuous reinvention – a voice both local and universal.

Yet support remains fragile. Government institutions often prioritise traditional arts, leaving experimental, contemporary works to private galleries and foundations. For Jeen, this makes his mission urgent: a safe harbour for voices that must be heard, especially those living under oppression.

‘Where art is censored, it reflects an unwillingness to embrace diverse perspectives,’ he says. ‘Where it flourishes, it enriches the public sphere.’

The Heart of the Matter

Htein Lin’s absence is, paradoxically, his presence. His story is one of survival, resilience and creativity unbound by walls or borders. Each brushstroke, every recycled sheet of paper, every word painted in Burmese is a testament to endurance, hope and unyielding spirit.

‘Art itself is the heart of the matter and the people who come to witness it are the soul,’ he says. Through screens, galleries and collaborators like West Eden, Htein Lin proves that no barrier – physical, political or social – can contain true artistry. His work is not just seen; it is felt, across time and space, reminding the world that even in adversity, beauty and hope can flourish.