[title]

While most art exhibits in New York City keep you at a distance, the Museum of Modern Art invites you to get closer at its new Hilma af Klint exhibit, “What Stands Behind the Flowers,” on view starting May 11.

Swedish artist Hilma af Klint is typically most known for “Paintings for the Temple,” her giant abstract artworks depicting geometric and organic shapes that she attributed to “divine messengers” or spirit guides. This body of work, however, takes its direction from af Klint herself and focuses on the natural world—highly detailed botanical drawing—in which she assigns a spiritual meaning to.

On view for the very first time, these self-studies ask us to attune to the natural world in a new way.

RECOMMENDED: See inside "Superfine: Tailoring Black Style," the Met's new spring exhibit

These 46 drawings, which are incredibly intricate and show every petal, every fuzzy stem and every color she observed in nature around her studio, were created in 1919 and 1920—more than a decade after her breakout as an artist. She’d already been working as a scientific illustrator and had trained as a landscape painter, so she was intimately familiar with the natural world as it was.

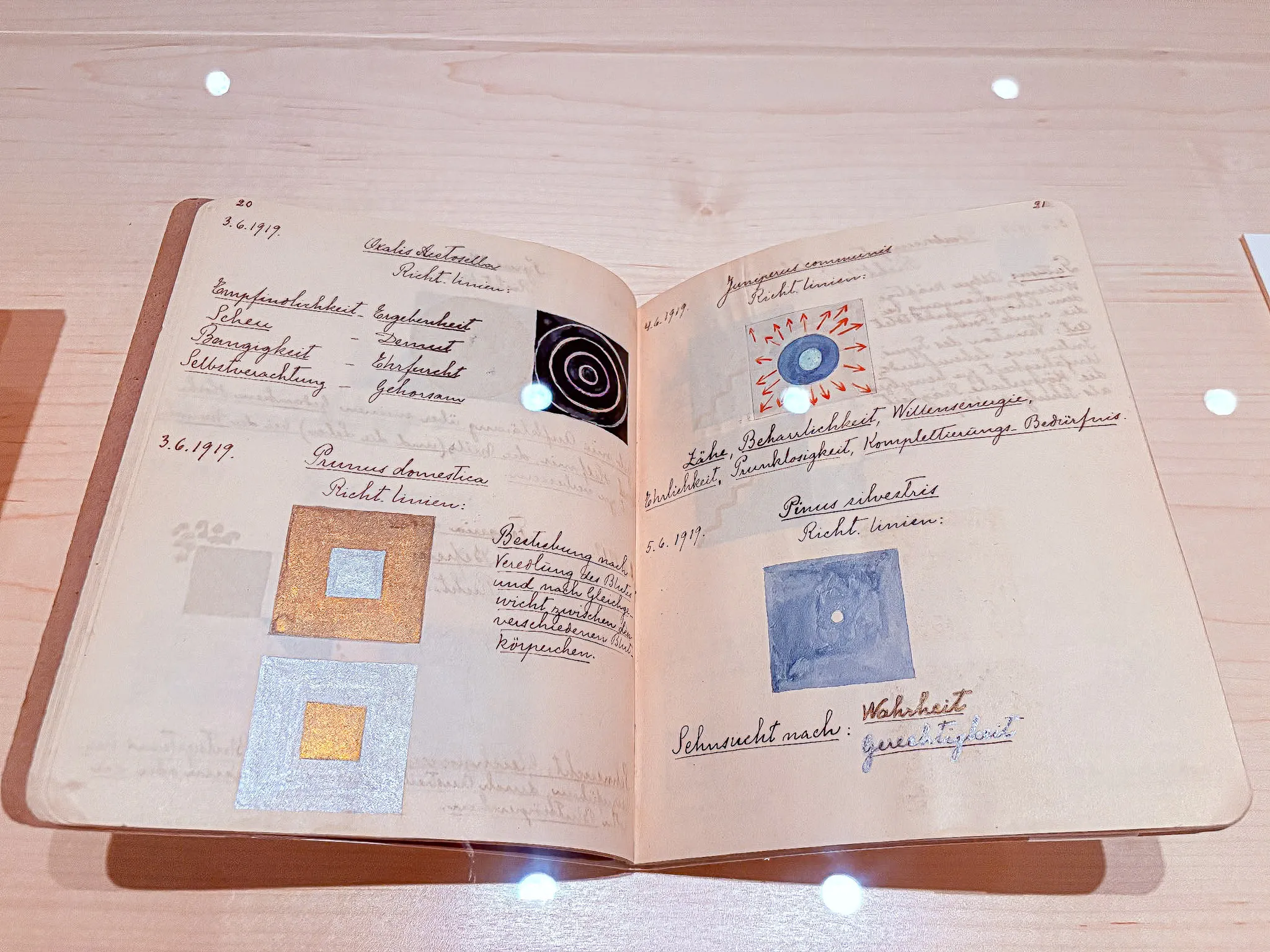

She first began this work in 1917, when she no longer wanted to get direction from her spiritual guides. She created a series of drawings depicting the smallest element of nature, the atom, which use checkerboard-like diagrams. Here, she begins to connect them to moral conditions.

“First, I shall try to penetrate the flowers of the earth; use as a point of departure the plants of the earth,” she wrote. “When we turn our gaze toward the plant kingdom, it gives us information about the composition of our own being. This world is the best textbook.”

Then, she collected and studied 114 plant species and recreated them on paper starting in April 1919. She continued to connect their particular aspects (the way they grow, how they function, what they look like) to aspects of the human condition, a state of consciousness or an aspect of character—finding a spiritual meaning in the flora she was cataloging. Each drawing contains “riktlinier,” a Swedish word for “directions forward” or “guidelines.” For example, in drawing the hepatica plant, which is a sort of buttercup perennial, she observed that it bursts out of the cold winter ground in the spring, signaling joy.

In each drawing, you’ll find the date af Klint observed the plant, its scientific and common name and its spiritual qualities. Sometimes there are even drawings of living beings like a bee or an ant, for example.

She created these works through September and again the following spring and summer.

Because her art is so intricate in this collection, it’s important to get as close as you can, according to Jodi Hauptman, the Richard Roth Senior Curator of MoMA’s Department of Drawings and Prints.

“Because she is looking closely, we want our visitors to really look closely,” she says, pointing out the magnifying glasses set out next to the artworks. Visitors are welcome to use them to see every detail.

The last section showcases a different kind of collection of works from 1922, after she concludes her extraordinary “Nature Studies.” Her interest in the connection between nature and spirituality is still present but the method is different. The series “On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees,” af Klint uses a a wet-on-wet watercolor technique that uses vibrant hues to express the spiritual power of plants.

The exhibit is beautiful, delicate, intricate and even provocative for those of us who live in New York City and often feel disconnected from nature. Perhaps there is something to that feeling we have when we get in the great outdoors. It seems Hilma af Klint was onto something.

See “Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers,” between May 11 and September 27 at the MoMA.