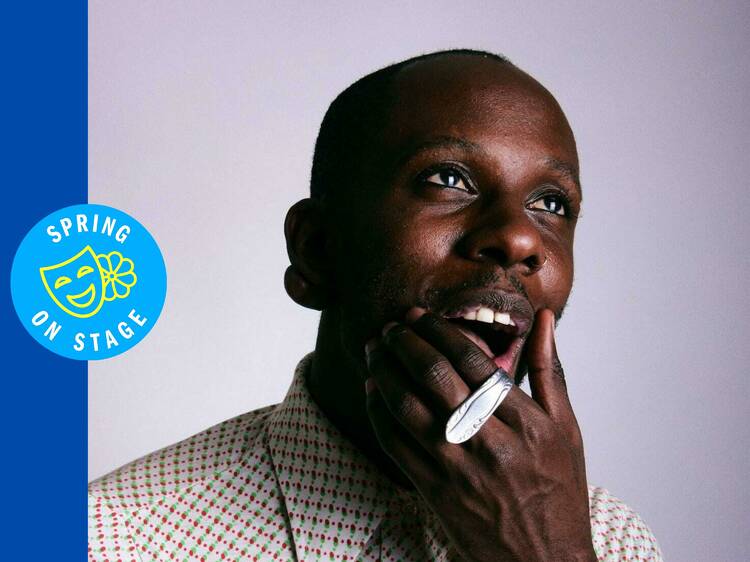

There’s no one in the dance world quite like the performer, director and choreographer Raja Feather Kelly. In the work he has created for his company, the feath3r theory, Kelly is known for his audacious maximalism and his witty, cerebral deconstructions of pop culture—Andy Warhol has been a particularly fruitful inspiration—all undergirded by an intensely intelligent compositional rigor. In recent years, this singular combination has made him wildly in-demand as a dance maker for ambitious Off Broadway theater works, including the back-to-back Pulitzer Prize winners Fairview and A Strange Loop. (His 2022 dance card is already crowded: He made the moves for On Sugarland and Suffs, and two other original musicals, Eighty-Sixed and Lempicka, will soon follow in San Diego).

Now Kelly is making his Broadway debut with the production of A Strange Loop that opens on April 26. Michael R. Jackson’s musical is self-referential, bold, flamboyant, achingly human and unapologetic in its questioning of what it means to be queer and Black while making art in an overwhelmingly heteronormative white space; in short, it’s unlike anything else on the Great White Way, and exactly the sort of project one might expect Kelly to be attached to. We spoke with him about representing the multiplicity of queerness onstage and feeling “like a landfill of culture in the best way.”

View this post on Instagram

Watching A Strange Loop, I kept thinking that I couldn’t imagine them having asked anyone else to choreograph this show.

Oh, that means so much! I think there was a time where I believed that I would not perform or make things on Broadway. I just thought that wasn’t where my career was headed, and so to see myself in the performers and to see my work on the stage is kind of a double whammy of excitement and joy and surprise. And then, for you to also say that you see me on the stage, although embodied by other folks, that’s very special.

How did you first come to be involved in the show?

In about 2016 or 2017, so many people would tell me that I needed to meet Michael R. Jackson. They were like, “It feels like Michael R. Jackson is the Raja Feather Kelly of musical theater, and that Raja Feather Kelly is the Michael R. Jackson of the downtown dance world.” We were both sort of unabashed in wanting to create space for our own versions of Black, queer life. When I finally met him at Joe’s Pub, he told me the other side of the story. I was like, “Hi, my name is Raja, people told me I should meet you,” and he was like, “Oh my god, you’re Raja! People told me that I should meet you!” We really became fast friends, and he asked me to come to a reading of A Strange Loop, which I did. I fell in love with it and I felt so connected to it.

What drew you to it?

I had been used to seeing very myopic views on Black, queer life. And what was so exciting was that, although this was written by one person and had some autobiographical content, it had a multiplicity to Black, queer understanding and expression. That is something that I am deeply invested in myself, so to meet Michael and to meet the cast and to celebrate their individuality in choreography and staging was something that really stood out to me as something that I could contribute.

Did coming back to it in the wake of the pandemic shift how you were approaching things in the process of bringing it to Broadway?

Just having more space has been such a thrill. I actually think, in some of the other productions, we have been bigger than the rooms that we’ve been in; an exciting part of the choreography is that it just didn’t fit. Now, I think, it really is creating more space for the characters to be more full and more exciting, and so I think the preparation was like, Everyone stick your arms out and take up space. That is a philosophical lesson and a beautiful luxury of Broadway.

From the very first number, each of the Thoughts—the six-person ensemble that surrounds the show’s central character, Usher—has such a distinct way of moving and taking up space, even in unison moments. How did you go about crafting that idiosyncrasy and pulling that specificity from these performers?

Crafting specificity, crafting the idiosyncratic, crafting detail: That’s what I do as a choreographer. I’ve always built ensembles; that’s something I love to do. I can’t take 100 percent of the credit. Each of these individuals is special and unique, so it was my job to empower them, and to let them express their individuality as movement and embody that. And then it was about turning up the volume, like, “Okay, that’s who you are, that’s how you express yourself, I’m going to add this and add that and continue pushing you to do more of that and to stylize it.” That was a process that, at each iteration, from Playwright’s Horizons to Woolly Mammoth to Broadway, is something that I just kept layering and layering and layering and layering. I want them to feel like themselves, but I also want them to feel highly stylized. I want them to look like dancers, I want them to feel like dancers. I treat them the way I treat my company.

There are sections where it would be easy to think that what they’re doing is improvised—that it’s natural, it’s just how these people move.

That’s a quality I’m really after, always: I want it to feel like it’s your behavior but I also want it to be so specific. I think I’ve gotten better at it. There was a time, I think maybe 2015 or 2016, when my company got this really shitty review because people thought that it was completely improvised, and was sort of chastised for appearing as if we were just doing everything on the fly. I remember my company being like, If that reviewer knew just how hard we work on getting those details, they wouldn’t have said that. Some of it obviously is their behavior, but it’s so specific and it’s so crafted.

Are there differences between how you approach your work with your company and your work in theater?

I try not to make them so different. The biggest difference is that for my company I am both the director and the choreographer. When I’m not the director and the choreographer, it’s more collaborative, because I’m working with the director and the lighting designer and the sound person in order to fulfill the vision of the writer, as opposed to fulfilling the vision of myself. I have a vision for the bodies onstage, and that’s connected to who they are and to the story. I want to make sure that that is pushing the whole story forward, not just a vision of the ensemble or the choreography.

In A Strange Loop, I caught very specific references to musical theater choreographers…

Oh, yeah. [He laughs]

…but presented in a very you way, and I’m sure I missed some. In the opening number I was thinking, Is that Fosse? Is that A Chorus Line?

Yep! There’s Fosse, there’s A Chorus Line, there’s Alvin Ailey…

I was wondering if I was just reading the Ailey into it!

It’s so there. There’s a little bit of all my influences. That’s something that's really exciting to me. And this musical is called A Strange Loop, so I feel there’s a permission slip to reference the thing that we’re doing while we’re doing it. In the opening number, “Intermission Song,” we feel like a performance is paused, so there’s that excitement of getting back to a show, that excitement of putting a show on. What are all the times that I felt that anticipation for the thing that I wanted? Any time I hear “5, 6, 7, 8,” I think of A Chorus Line no matter what. There’s Michael Jackson, there’s Janet Jackson, there’s Britney Spears, there’s all of that culture that influences who we are and what we’re thinking about in our bodies. I wanted that to exist. Especially when I think about what queerness means to me—how I feel like a landfill of culture in the best way. It’s all here, it’s all in our bodies, so why not explore that? Why not celebrate that and interrogate that as choreography itself?

That’s something that’s so important to the book of the musical as well—all these influences, the multiplicity that makes you who you are as a person. How do you arrive at what you want to reference in a given moment?

I think the ideas come from the rehearsal room. I don’t make anything before I get into the room. As we’re talking, sometimes it’s an impulse: I hear the music and I’m like, “This makes me think of Britney Spears,” or, “The bass in this makes me feel like it’s Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller.’” Sometimes it’s, “Let’s just do a music workshop today where we find movement together.” And sometimes it’s, “Have you all seen Revelations by Alvin Ailey? There’s a moment in the show that is a revelation, and wouldn’t it be funny to just quote Revelations?” I felt like it was important in conversations that I’ve had with Michael where I’m like, “What are we influenced by? We both love Beauty and the Beast, so let’s add some,” or, “We really love this thing that Beyoncé does, let’s add that.” And sometimes, when I share my stylistic choices, I’m like, “Do you guys know who Trisha Brown is? Do you all know who Pina Bausch is?” These things live in my body because I’m trained, and I like sharing those things with the company of A Strange Loop. This moment feels like this, so let’s make that feeling a real thing. I think it’s exciting to quote because it gives people access in a way that I think is full of joy.

A moment I found really striking was when the idea of Tyler Perry and a gospel play started coming up, and the movement went into things like basic jazz squares and Charleston steps.

So much of the musical is Usher asking, “What are you asking me to do? What is everyone asking me to do?” And in that moment in particular, I think Usher’s agent is asking Usher to use his Blackness to make him money. That is seeded in the history of minstrelsy, vaudeville, Blacksploitation. So those references in that moment are that. How do I reference what is being asked of Usher in this moment, and why Usher is against it? Usher doesn’t want to perform in blackface, Usher doesn’t want to perform the shuck-and-jive just to make money. So that’s why in that moment the agent is like, “Yeah, that’s great,” and Usher’s like, “And that’s exactly the reason why I am not doing it, because I refuse to exploit myself.”

And then later, the Thoughts are playing the role of the gospel choir, and it reaches the point where they break into twerking. It feels like the subconscious coming through.

I love that you saw this moment! They’re just singing, “Pray, pray, pray,” right? Isn’t it interesting how this rhythm could so easily slide into something else? And again, it’s about the exploitation of it. You think this is one thing, where they’re just step-touching and praying, but actually they become objects, and they become sexualized. It’s about wanting to make a strange loop out of the choreography. You see them step-touching, but you also see them taking pleasure in the rhythm of the music; it’s going inside of their brains for a moment, and then unpeeling and coming back to the image that you think you’re seeing. You think you’re just seeing them step-touch and bop their heads to the church music, and as you go deeper into the pleasure, it’s like, “Actually, I just want to do some twerking, I want to crawl on the floor and shake my ass, and be empowered by rhythm and music and my sexuality…But actually, no, I take it back, I just want to make a moment that’s about praying and exalting the Lord.” [He laughs.] And that lives in the body! Both of those things live in the body. They’re both there. It’s important to show, again, that strange loop of seeing and being seen, of spirituality and sexuality, of pleasure and objectification and empowerment, all in one moment.

That use of almost visual dissonance is something that both Michael’s writing and your choreography do: turning a scene on a dime. Something shifts, and you can’t quite put your finger on how it happened. Like in the number “Inwood Daddy”—there’s a kind of robotic showbiz vibe to the choreography, very rhythmically even and simple, while this uncomfortable encounter plays out.

That’s where I realized that Michael and I are interested in the same stuff. It was exciting that I was given the space to choreograph those things, because I think about those things. It’s kind of like MTV’s True Life: You think you know, but you have no idea. That’s how I think Michael writes and that’s how I choreograph.

In contrast to the muchness of so much of the show, whenever there are moments that are very simple, they are exquisite, like the floating up of the arms in “Memory Song.” I imagine it was a conscious choice, taking that moment to breathe.

Many people might not know how hard that is to do. It can be easier to create a lot of organized chaos, although it’s difficult to make that look structured and have craft, but it’s just as challenging to hold stillness and to move slow. Originally, I think, that number was meant to be a solo for Usher. But having the cast there and teaching them to hold space for Usher and for the idea of that song, and to be still and to be seen all at the same time… for me, having that—having the opening number and then having that number—makes for real, well-rounded choreography and storytelling and shows the power of the body.

In dance, there are so many amazing, virtuosic things or wild, out-there things that can be done, but it’s the spaces in between that allow those moments to sing.

It’s also, to me, a very queer idea—the idea of showing the layeredness and multiplicity of queerness. I think people might see the words “big, Black and queer-ass American Broadway show” and expect us to throw our hands up and expect people to shake their ass, and I’m like, You think you know? [He laughs.] You have no idea. Because queerness is throwing your hands around. Queerness is an unabashed expression of self. But it can also be thoughtful, and investigative, and contemplative, and soft, and internal.

I often think that one of the biggest gifts that comes from discovering and investigating queerness for yourself is that it invites you to ask those questions and to sit with yourself in that particular way.

I don’t think everyone thinks that. But I certainly do, and I know Michael does, and hopefully more people will after seeing something like this at this scale. I think it’s so special that choreography like this exists on Broadway, and I feel so honored to be at the helm of that. I’m super proud of the performers and Michael for inviting me and trusting in my vision for A Strange Loop.