The great thing for theater lovers in New York City is that at any given moment there's a dizzying array of musicals, plays and experimental works to choose from. Here is a short list of shows that Time Out New York's critics recommend.

Still rakishly handsome at 77 and able to exude an essence that’s simultaneously posh and unpretentious, master playwright Tom Stoppard has, in recent weeks, been leading a transatlantic life. And while he’s never shrunk from the spotlight, the chatty and photogenic scribe would rather like to get back to writing, not shuttling from rehearsals of The Real Thing to previews of Indian Ink, the two Stoppard plays the Roundabout Theatre Company is currently reviving. The Real Thing returns to Broadway for the third time, starring Ewan McGregor and Maggie Gyllenhaal as adulterous lovers who find passion and trust to be combustible elements. Indian Ink is another romance, this one between poet Flora Crewe and colonial India, specifically a local painter she meets there. Both works are classic Stoppard: brainy, sexy and stuffed with quotable gems—something the writer provided a fair share of during his lunch break at The Lambs Club.

SMOKING IN THE LIBRARY

I just wanted to say I’m a big fan of the London Library, of which you’re the president. For a bibliophile, it’s a wonderland.

I love the place.

Do you write much there?

No, I take books home—sometimes ten or 12 at a time. I don’t write at the library, because I smoke when I work or would like the possibility of a smoke. Also, I need to be at my own desk. With plays that require any kind of reading program, I’m reading for a couple of years before using the material.

Is there any correlation between how much you smoke and productivity?

I smoke too much whether it’s going well or badly. After all these years, I definitely associate having a pen in my hand with having an ashtray just out of eye line.

ON HIS NYC DOUBLE BILL

The Roundabout is reviving one of your best-known plays, The Real Thing, and a relatively obscure one, Indian Ink. Was the pairing their idea or yours?

A bit of both, actually. What happened was the ACT did Indian Ink in 1999, when it was a new play. And [ACT artistic director] Carey Perloff did a very nice job with it. She was always hoping, and I was too, that she could re-create her San Francisco production in New York, maybe at the Roundabout. So that conversation started soon after the ACT premiere. Then the Roundabout asked about doing The Real Thing at the American Airlines. And I rather ruefully said, “Yes, thank you. By all means, do, but if you want to do one of my plays, we’ve been asking you to do Indian Ink for ten years.” Then they decided it would make a kind of sense to have them both on, in those two houses.

Thematically, what connects them?

Not trying to be clever, but I wrote them both. It’s a kind of tautology. They don’t have much to link them otherwise. Love is important in both plays, but it would be hard to name many plays where love isn’t important. I’ve always been strangely eclectic. I don’t think of my plays as having that kind of continuity with each other.

And yet, you often write about the inadequacy of thought, or idealism, to create lasting social change. Like The Coast of Utopia, which boiled down to: Don’t put philosophers in charge.

Well, I like plays where people talk a lot. Conversation is sustained. Argument is sustained. It’s slightly misleading to think there’s some kind of choice you’ve made. You are the plays you write. How on earth could you write them otherwise? They’re projections of your own predilections. And mine tend to be about something quite abstract underneath. Coast of Utopia was about real people doing real things. But its real subject matter was something like radicalism, rather than the adventures of the Russian exiles. It was an argument that kept going. I essentially write things that please me, interest me. Then one just finds out whether it works as theater or not.

ON HUMAN EVOLUTION

I’m dying to know your latest play, The Hard Problem, debuting in January.

I’m pretty much delivering it now. I’ve been failing to write this play for years, just not doing it. Thinking about it. Nick Hytner is leaving the National Theatre next year, and he asked me to write one for him to direct before he left. And I thought, Well, that’s quite good to have a deadline. And the deadline is now.

Can you let the cat out of the bag?

The play is set in the world of people who do evolutionary biology. It’s essentially a play set among scientists and psychologists. But it has a story. It’s not an essay, you know. It’s about people who are researching.

Contemporary?

It takes place over a little span of time. Probably sets off around the millennium. So it’s contemporary but not up to the minute.

Are humans still evolving?

I guess we’re still evolving, as far as anybody knows. It’s really a play in which the characters are concerned with the problem of consciousness—what consciousness is and why it exists. That’s probably all I should say about it.

SCRIPT DOCTORING FOR GEORGE LUCAS

This is your first time working with Ewan McGregor, right? That’s a trick question: Didn’t you work uncredited on George Lucas’s Revenge of the Sith?

Which one was that?

The third of the recent prequels.

I did talk to George about one of the episodes. It must have been ten years ago. Actually, it was Steven. Steven Spielberg asked me to read a script and do a kind of dialogue polish. I did a bit, but I wouldn’t want to usurp the writer’s claim on the movie. [Laughs] Polish is such a strange word for what one does. I interfered with George’s script in a mild way.

“Interfered.” That’s a very Ortonian way of putting it. Ortonian or Etonian, I can’t decide which.

[Chuckles] Well, you know, it’s slightly misunderstood. It’s not structured like you’ve got this job to do. It’s more like spending time with friends and giving a hand. I didn’t even know Ewan was in the film.

He played the Alec Guinness role. A younger version of Obi-Wan Kenobi.

Oh. I wonder if he got to say anything I wrote. I must ask him.

MARRIAGE AND THE REAL THING

You recently remarried, didn’t you? Sabrina Guinness?

Three months ago. Yeah, I like being married. Haven’t been married for a long time actually.

In The Real Thing, Henry, a witty English playwright, leaves his wife for an actress. But the play’s not really autobiographical, is it?

No, except that Henry’s prejudices tend to be mine. But I had to make up the story, as usual.

And yet, a few years after it, you did have a relationship with actress Felicity Kendal, in the wake of your second marriage. Art was not imitating life, but life imitated art, down the road.

That happens more often than people think.

DREAMING OF INDIA

Indian Ink must partly come from personal history. You lived in Darjeeling from 1941 to '46 as a boy. Were you awash in childhood memories writing that?

Yeah, I was. But the Indian part of the play is set in 1930, before I was born, when the country was really colonial. My mother, brother and I weren’t British Raj; we were Czech refugees. But India itself—I loved it. And I dreamed about it for years, after I came to England. I was no longer a boy. I was still dreaming of India. I went back, once, in my forties.

For research?

Not research, no. I had the opportunity to revisit where I lived and went to school, in Darjeeling. And a magazine didn’t send me but said they’d run a piece I’d write. And I had a friend, a photographer, who was Indian and was going there, so it was a good opportunity. I felt very at home there.

You were a Czech immigrant in India. Your mother met Major Kenneth Stoppard there and married him, and he, in way, made everyone British. So do you consider yourself, in a way, a person who was colonized?

You know, essentially, we were white. We were European. So we were part of that split culture, sort of ruling class. We didn’t have servants, the way somebody rich would have. We were poor. Although my brother and I had an ayah [nanny].

Is there any of your stepfather in Indian Ink’s British officer, David Durance?

David Durance is quite a typical young man of the time. I didn’t need my stepfather to make David up. No, I was really interested in the milieu that Flora Crewe comes from, the London literary crowd. Bloomsbury started a lot earlier than 1930, but it was that culture. When I was young, I aspired to that world, even met people who were in it. Now I look back on it with great affection. I was enthralled by it.

YEARS AS AN INK-STAINED WRETCH

In the mid-’50s you were a newspaperman and then moved to London to write for magazines and eventually plays. Was journalism good preparation for playwriting?

Not particularly. I was just thrilled to be allowed to write something that was printed. It was beyond my wildest dreams.

In your journalism days, you were a second-string theater critic for a while, weren’t you?

That’s dignifying what I did, but you’re right.

Did your time in the reviewing trenches give you more or less sympathy for us critics and our ilk?

Because I think of drama critics as coming from my own world of journalism, I don’t consider them as some form of opposition. But I think drama criticism is extremely hard to do well. I understood completely when I went to Russia and discovered that to be a critic you have to pass a three-year degree course. I understand that. Writing about writing is part of the culture. It’s a definite skill. To be a Russian critic of Chekhov is a different thing to writing briefly and quickly about a production. I rather envied that in Russia. I wasn’t a good critic. I thought that any given entity on the stage or, indeed, on the page had a certain value or score, out of ten, if you like. And I had to figure out what that number was. I was too timid to understand that there’s nothing you can write about except what it does to you as you sit watching it. There’s no other criterion for making a value judgment.

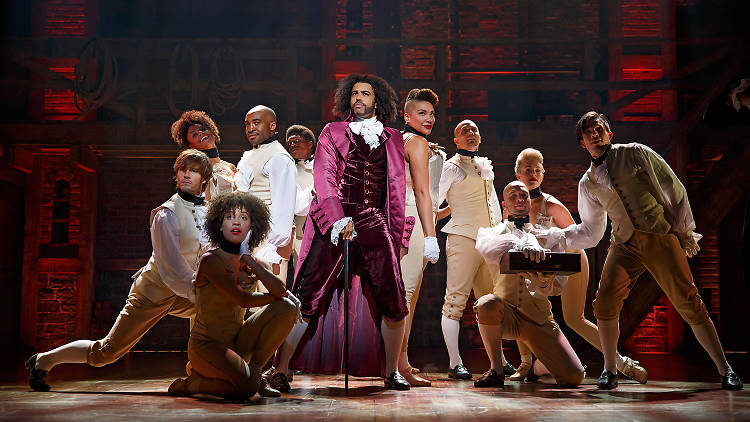

The Real Thing opens Oct 2 at American Airlines Theatre.