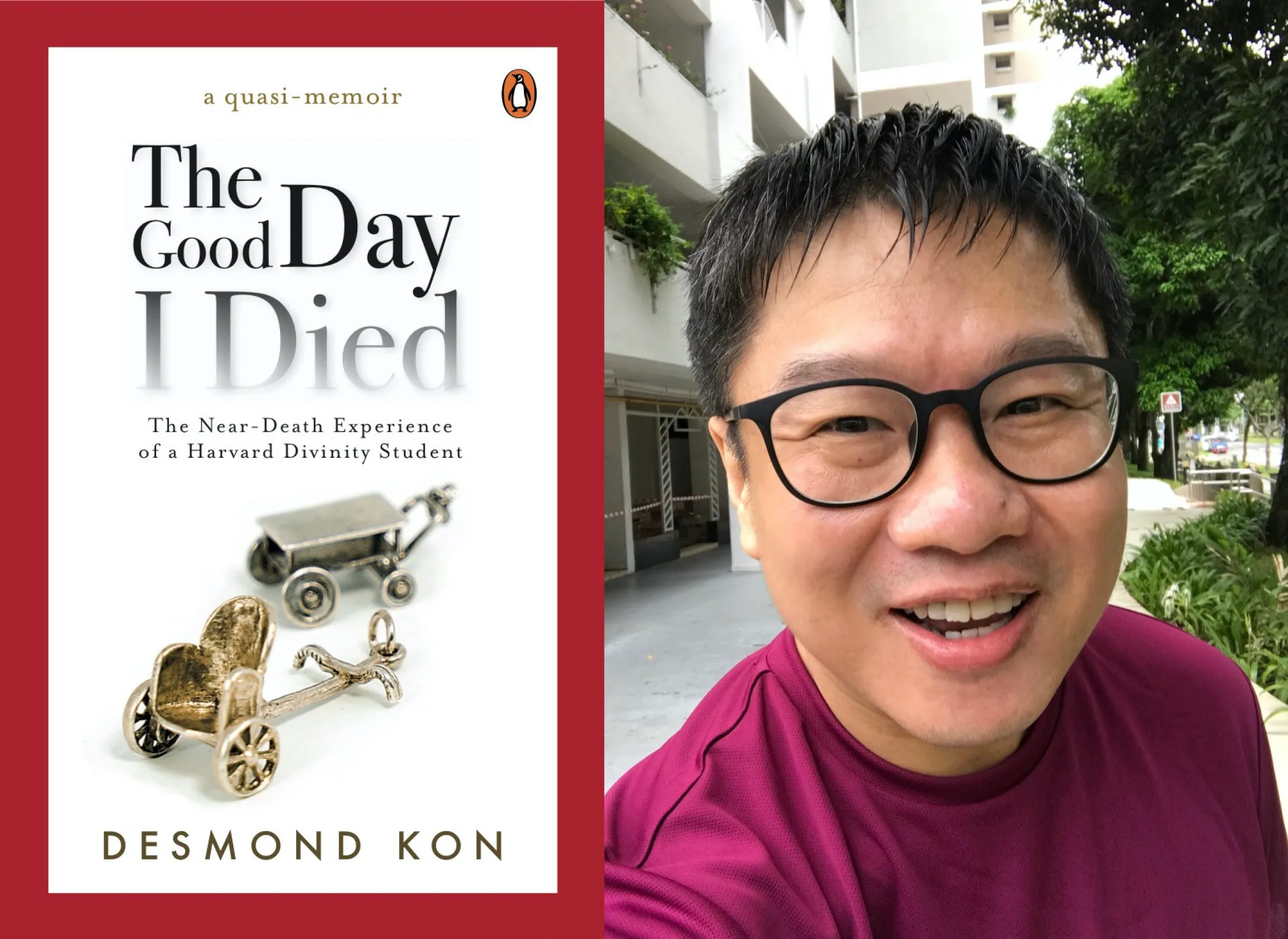

For avid readers of Sing Lit, the name 'Desmond Kon' is a renowned name in Singapore's literary scene. After all, poet, former journalist, interdisciplinary artist and founder of Squircle Line Press has penned an epistolary novel, a quasi-memoir, two lyric essay monographs, four hybrid works, and nine poetry collections.

His latest novel, The Good Day I Died, speaks about his near-death experience (NDE) that happened while he was in Massachusetts, just as he'd completed his theology masters in world religions at Harvard the year before. We chat with him about the quasi-memoir, what happened during his NDE, and how it has changed the way he lives his life.

You had your NDE in 2007. What inspired you to finally write and publish The Good Day I Died?

It was free therapy. Like self-talk therapy – well, closer to narrative therapy, when you think of it.

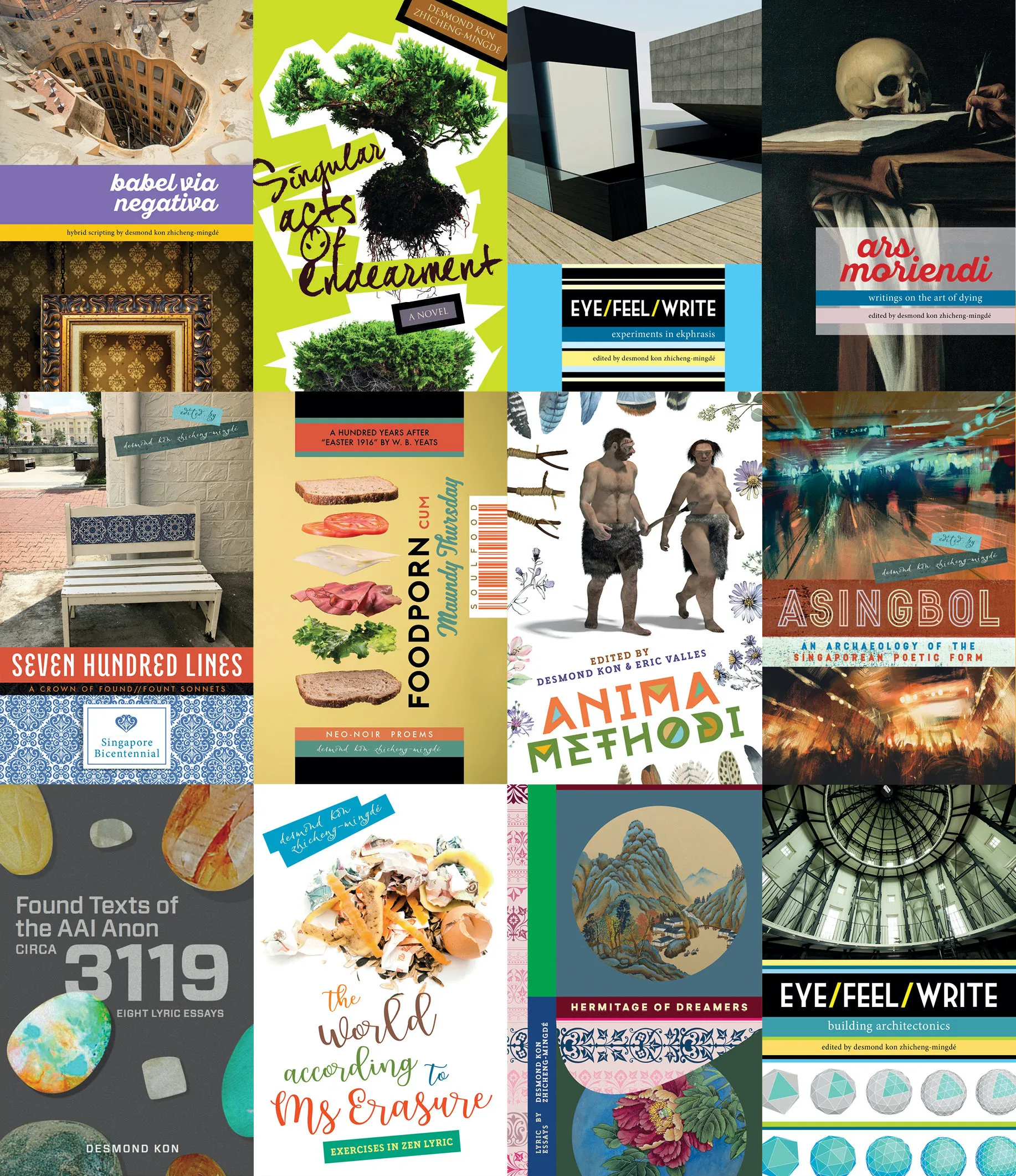

That, and at some point, I realised I’d reached some level of comfort with relating this personal account. Also, I realised so much of my oeuvre dips into the NDE in some way – no matter how obscure or tangential – that it seemed a fine moment for the story to be told proper. How the NDE infused or imposed itself on my literary output thus far – almost as a recurrent ekphrastic source within a narrative trajectory – strangely felt more like a natural evolution.

By the time I decided the NDE warranted a dedicated book of its own, the drive to write it all out was nothing short of a compelling force.

The NDE practically wrote itself out – I say this because much of the memory and recount emanated from my subconscious – as poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, lyric essays, hybrid texts, even a playscript. The book features extracts that can be seen as alluding to ideas of death, being, consciousness, angels, the afterlife, among many other things.

In fact, I had to leave out a lot of material from my other literary works to maintain the textual integrity within the quasi-memoir. I wanted to achieve a fine balance between the different textual treatments. Actually, I’m still discovering new texts within my oeuvre that clearly were inspired by the NDE.

What exactly is a quasi-memoir?

A quasi-memoir transcends the conventional autobiography and all the reader expectations that come with the genre.

My book is, on all counts, essentially a memoir, but intensely self-aware and self-critical. It’s self-conscious writing – the tone honest as humanly possible, yet endlessly cautious—how scrupulously concerned it remains about the limits of language. A way-cool example of a quasi-memoir is David Lynch’s Room to Dream, a braid of biography and memoir. There’s also José Paulo Cavalcanti’s quasi-memoir of the famous Portuguese poet, Fernando Pessoa.

Framing my book as a quasi-memoir was a deliberate choice. I like the prefix “quasi-”, derived from Latin, which translates to mean “almost as it were; as if; analogous to”. I love how contingent it makes everything seem, how everything should be looked at or read into.

That said, if you were to ask me point-blank whether the NDE actually happened, yes, it’s true that it did. That much is certain.

It was the responsible thing to do as a writer, at least for me. For one, the whole study of consciousness is rather recent, and everything is still being explored and discussed in such healthy discourse. Truth is not something to take lightly, especially with phenomena that defy easy understanding or expression, no matter how personally true they may seem.

Too many people speak of truth nowadays, with little heed of its inextricable intertwining with history, context, language, knowledge, power, intentionality, interpretation, all the complexities of meaning-making. From a philosophical standpoint, one could deconstruct the nature, the property of truth. Truth, too, can be viewed as a construct.

To add, my book is peppered with excerpts that range from poetry to fiction, even as they’re all meant to scaffold and augment the whole matter of my NDE.

Can you tell us about your NDE?

I died in the attic, on the third floor of a rented house in Massachusetts. I’d completed my theology masters in world religions at Harvard the year before. I found myself entering an otherworldly realm, what I perceive as the afterlife. It was all very intense, and I felt such extreme states and emotions – of awe, fear, wonder, reverence, ecstasy, serenity, love. It was completely life-changing.

One thing I remember: I wished I’d meet my grandmother there, come to take me home the way she did in Primary One. Sadly, that did not happen – I didn’t get to see my Ah Ma.

Did you realise you were experiencing an NDE at that moment?

Yes and no. That’s the odd paradox of the entire experience, a kind of liminal space. I knew I couldn’t have been transported to this strange realm in that short time; yet, everything felt real as rain, real as my yellow wall paint. I gazed in awe at the beings of light, these divine messengers, wondering whether these angelic beings matched with what I’d studied in my angelology class.

Ironically, it was so real an experience, I thought I was still alive the whole time. It didn’t actually register that I’d died, despite my friend who resuscitated me telling me so. Indeed, it took years before I finally came to terms with the fact that I’d actually died, passed into the afterlife, and returned. Such a drawn-out delay, averaging seven or more years, seems a common statistic shared among numerous NDE witnesses, according to research.

We often hear of NDEs, how different is the real experience, etc?

There are copiously documented NDE accounts from people across the world. They run the gamut of identity and culture. There are several commonalities across these NDE accounts. For instance, having an out-of-body experience. Encountering otherworldly beings. How time and space function differently in this altered realm. Yes, the classic tunnel of light. And of course, the return to consciousness and this mortal life.

There’s simply too much to offer sufficient treatment here. Now’s a good time as any to give a shout-out to my awesome publisher, Nora Nazerene Abu Bakar of Penguin Random House, who just released the book as an eBook Kindle edition for worldwide purchase on Amazon.

The paperback is also available at Kinokuniya. If anyone would like a signed copy, you can purchase it off my author website. I’ll make sure to inscribe it with any message of your choosing, and happily mail it out to you soonest.

In retrospect, everything happens for a reason. Why do you think the NDE happened to you?

Maybe it runs in my veins. My mum says there’s a distinct pastoral lineage in the family tree. My maternal great grandfather was a missionary, and founding father of a church in Malaysia. My second sister, Lorinne, also studied theology in America. She authored a devotional book with my dad in 1999. My dad, a publisher himself, went on to author another four of them. Seems these pietistic inclinations run in the family.

I did consider becoming a man of the cloth, take up holy orders and all. Alas, I ended up falling in love with poetry, all of the belles-lettres really. My other great-grandpa was a wine merchant, so that explains the clam-happy-happy-camper me, after knocking back a few.

I might not seem this way – my being such a flippant bonehead at times – but I’ve always been a deeply spiritual person. My entire life seems like an enduring search for God, to have that encounter with the divine. So, I guess I had the NDE coming (nothing short of a blessing, really).

How do you think your experience has prepared you for death?

In a class on Death & Dying at Harvard Divinity School, my professor mentioned how little people even thought of death, not until they had to confront it in their life in some way. It’s true, isn’t it? Death is such a dreaded topic, and many people avoid it, much less contemplate it.

In his essay, To Philosophize Is to Learn to Die, Montaigne opens with Cicero’s remark that “to philosophize is nothing else but to prepare for death”. Seen in that way, all our constant self-doubt and introspection—all our beating ourselves up over ourselves—helps nudge us along this journey towards our eventual passing, and the great beyond.

It gives meaning to all the times we’ve been made to question our every thought, emotion, decision, action. I turn the big 5-0 next year, so I figure I’m into the last third of my life. It’s great being this age. Everything I used to fuss over now seems quite trivial and silly. I’m happy to declutter, given the clarity that I won’t be able to take anything with me when I do croak, go west, bite the dust, buy the farm and ranch.

“What you are is God’s gift to you,” Hans Urs von Balthasar said, “what you become is your gift to God.” So, I guess there’s that tall order too. To become someone whom I wouldn’t be embarrassed to be – the hope that I can be accountable and responsible for my life decisions – when I do meet my Maker.

How did it change your perception of death?

John Lennon said that he wasn’t afraid of death. “It’s just getting out of one car, and into another.” That’s what Lennon thought of death. I came back from the hereafter, knowing I needed to utilise my second lease of life better. These days, I’m more interested in immersing myself fully in my present lived experience.

I’m still on that path. I doubt many people have the confidence to say they’ve arrived when it comes to finding that ultimate happiness during their lifetime. I certainly can’t. I was glad though, to sacrifice a lot of the indulgences and illusions post-NDE, which ironically issued a real sense of personal freedom.

I live a much more intentional life nowadays. I attend to things that bring deeper meaning to my time here on this good earth, like art, teaching, writing, reading, editing. I’m a through-and-through nerd, stodgy and tediously boring. The dull scholarship is hardly colourless for me. It’s glint and glitter, the way it jazzes everything up puts the zip in what seems like bleaker mornings for the world these days.

I make it a point to open and close each day with contemplation. Prayer is exceedingly important. I pay attention to nurturing my spiritual life. I’ve very conscientiously tried to create a lifestyle that builds in this purposefulness. Each life moment is precious, and I try to be as present as possible to the moment.

Having experienced near death, what’s your advice to our readers on making meaningful use of their time here on earth?

I hope this book helps readers contemplate their own life purpose, station and agency. That they will be the kinder for it, the humbler for it, the more grateful for every small blessing. That they manage to examine for themselves what might constitute a good life. The quicker people decide what gives their life greatest meaning, the quicker they can chart their own journey towards that end.

I’m ultimately a God-fearing, God-loving bloke, so I only wish everyone else their own existential paths that bring them closer to the happy bliss we search for.