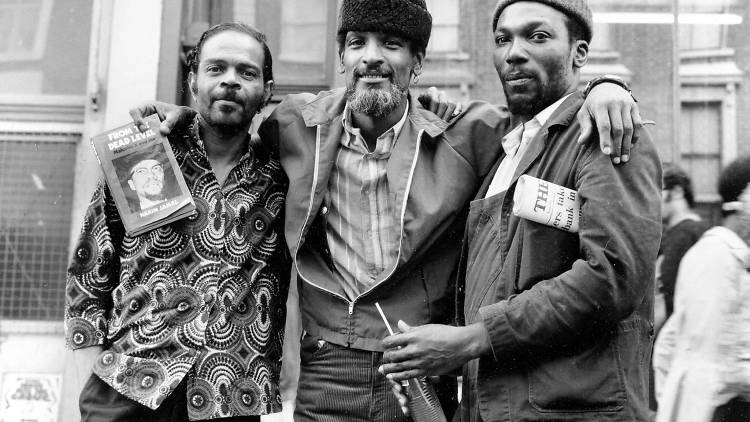

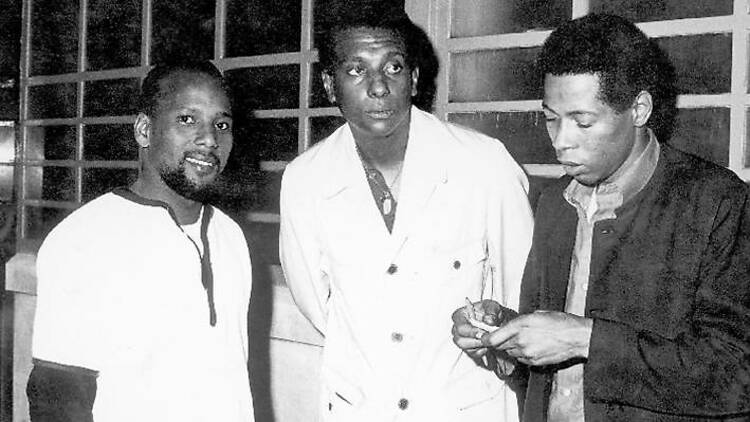

Black Panther Hakim Jamal (centre) on the Portobello Road, 1971

Charlie Phillips is the greatest London photographer you've never heard of – and some of his best works are only just being rediscovered. Time Out meets him and hears his story.

Charlie Phillips lives alone in a small house in Mitcham, south London. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the place is a mess.

Let me make you some coffee,’ the 70-year-old offers as I arrive to interview him about his remarkable life and equally remarkable photographs. ‘Jamaica Blue Mountain Coffee – the good stuff,’ he says, before turning to rummage through a precariously overstuffed cupboard. I’m amazed Phillips manages to find anything in this place, which is packed with memorabilia. Cameras, cassette tapes, negatives, magazines – they cover every available surface.

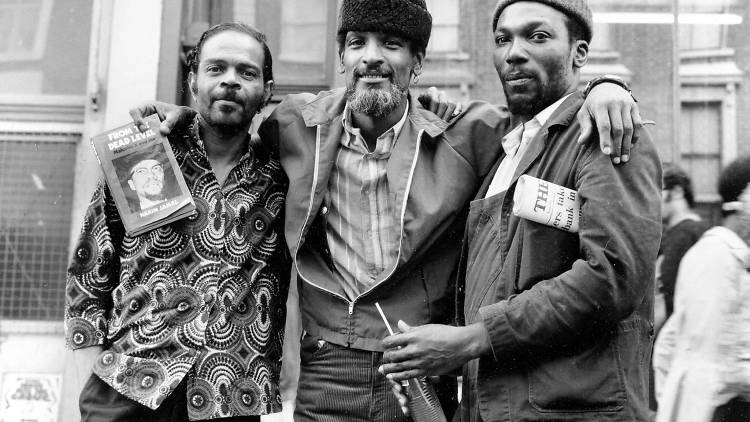

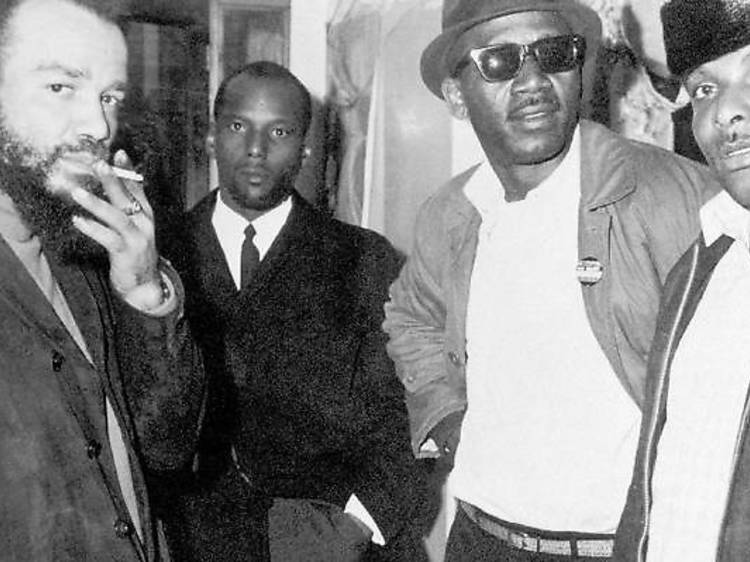

It’s understandable, perhaps, that it’s taken so long for people to recognise Phillips as the seminal London photographer he undoubtedly is. His images include stark portraits of Windrush-generation west Londoners, taken during the ’60s, snaps of global icons such as Muhammad Ali, from his time as a journeyman paparazzo, and tens of thousands of photographs of Afro-Caribbean life in the capital. It’s a startling body of work, but it’s taken a long time to come to light.

Last year Phillips was visited by curators from Photofusion gallery in Brixton, who offered to sift through and archive some of his shots. They found box upon box of material, most of which was stashed under his bed, including images taken at the hundreds of funerals that he had attended over several decades in London. The photographs they unearthed produced last year’s exhibition ‘How Great Thou Art’, which put him back on the map, not only as a great photographer, but also as a vitally important chronicler of black London.

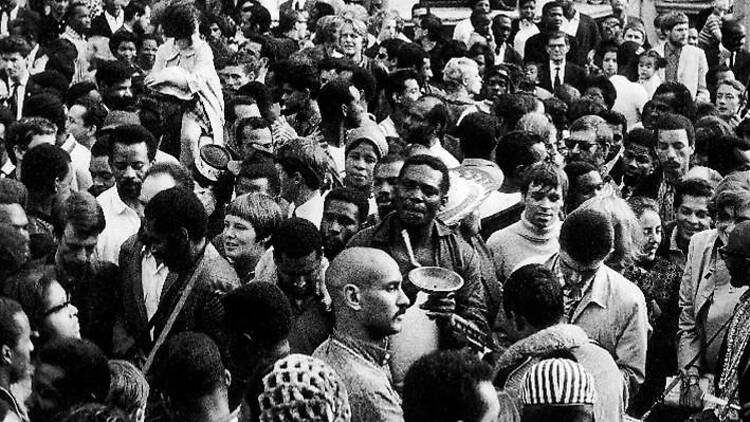

‘People think I’ve led an interesting life,’ he says. The hunt for coffee now abandoned, we switch to Mount Gay Rum (also ‘the good stuff’), and he begins to tell me about it. Charlie was born in Kingston, Jamaica. But he begins his story in Notting Hill in the late ’50s, where he moved aged 11. ‘Certain parts of [Notting Hill] were no-go areas,’ he says. ‘There were race riots.’ There were also brutal murders, committed by fascists. Which were in turn followed by buzzing, defiant Afro-Caribbean funerals. Phillips had a Kodak Retinette camera, left behind by an American GI who was staying with his parents in Portobello Road, which he used to photograph these events, as well as the ’60s street parties that were the roots of the present day Notting Hill Carnival.

‘I was in my darkroom,’ he remembers, of an early carnival in 1967. ‘And I heard all this commotion – I thought it was a riot. But it was just a way to let frustration out, and have fun.’

Having travelled the world through his teens and twenties – living la dolce vita in Rome for much of it – Phillips returned to London in the late ’60s. ‘We called it the Beat era,’ he says. ‘Allen Ginsberg, Peter Cook, David Hockney, Stokely Carmichael, Jimi Hendrix...’ he reels off the names of the greats he hung out with and photographed. ‘I was with Hendrix four days before he died,’ he adds. ‘Man, but my Jimi collection is lost.’

That’s the problem that Phillips now faces – a lot of his best work has disappeared, or is still waiting to be discovered by the helpers sifting through the boxes in his house. A few major cultural institutions have begun to recognise Phillips’s importance – the V&A, for example, have acquired some his iconic ’60s shots – but it all feels a bit late. From his perspective, he feels like he’s been sidelined.

‘Culture: it’s become very elitist and sometimes very corrupt as well,’ he argues. ‘This is the urban view... so how do you get into the establishment?’

He checks himself a moment. ‘I’ve been advised: Don’t get too political. But I’m 70 now, so what the fuck!’

Phillips has every right to grumble. His work reveals the sides of London which are so often misrepresented or simply ignored. Like his images of Notting Hill, for example, including the striking portrait of a stylish couple that he now pulls out from behind the sofa. ‘What really pisses me off,’ he says, concluding his rant, ‘is when they made that horrible film, “Notting Hill”. There wasn’t even one person of bloody colour in it!’

Phillips’s older photos might be in black and white, but they say vastly more about London life than a Richard Curtis film, that’s for sure.

Discover Time Out original video